Architecture and drawing go hand-in-hand – a phrase that underlines the manual history of both the building and the sketch. As technologies and mediums for drawing expanded, so have the definition and use of the architectural drawing. Members of the Design Communications team at Foster + Partners reflect on their place in the practice of drawing in the Foster + Partners studio, and its ability to question what might be possible for a design.

16th May 2024

Seeking a Visual Language: Drawing and Design Communications at Foster + Partners

This is how space begins … signs traced on the blank page.

Georges Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces

Foster + Partners, since its founding as Foster Associates in 1967, has long produced, commissioned and endorsed a range of architectural drawing styles, often challenging the definition of what a ‘drawing’ might be – from Letraset and airbrushes to Apple Pencils and animation. The practice’s founder, Norman Foster, is renowned for never being without a sketchbook, and has published several books and essays on the architectural sketch. At the other end of the spectrum, construction and presentation drawing was an in-house skill from the beginning, with architects manually drafting designs for planning reports, and plans for publications (before the commercial use of the computer).

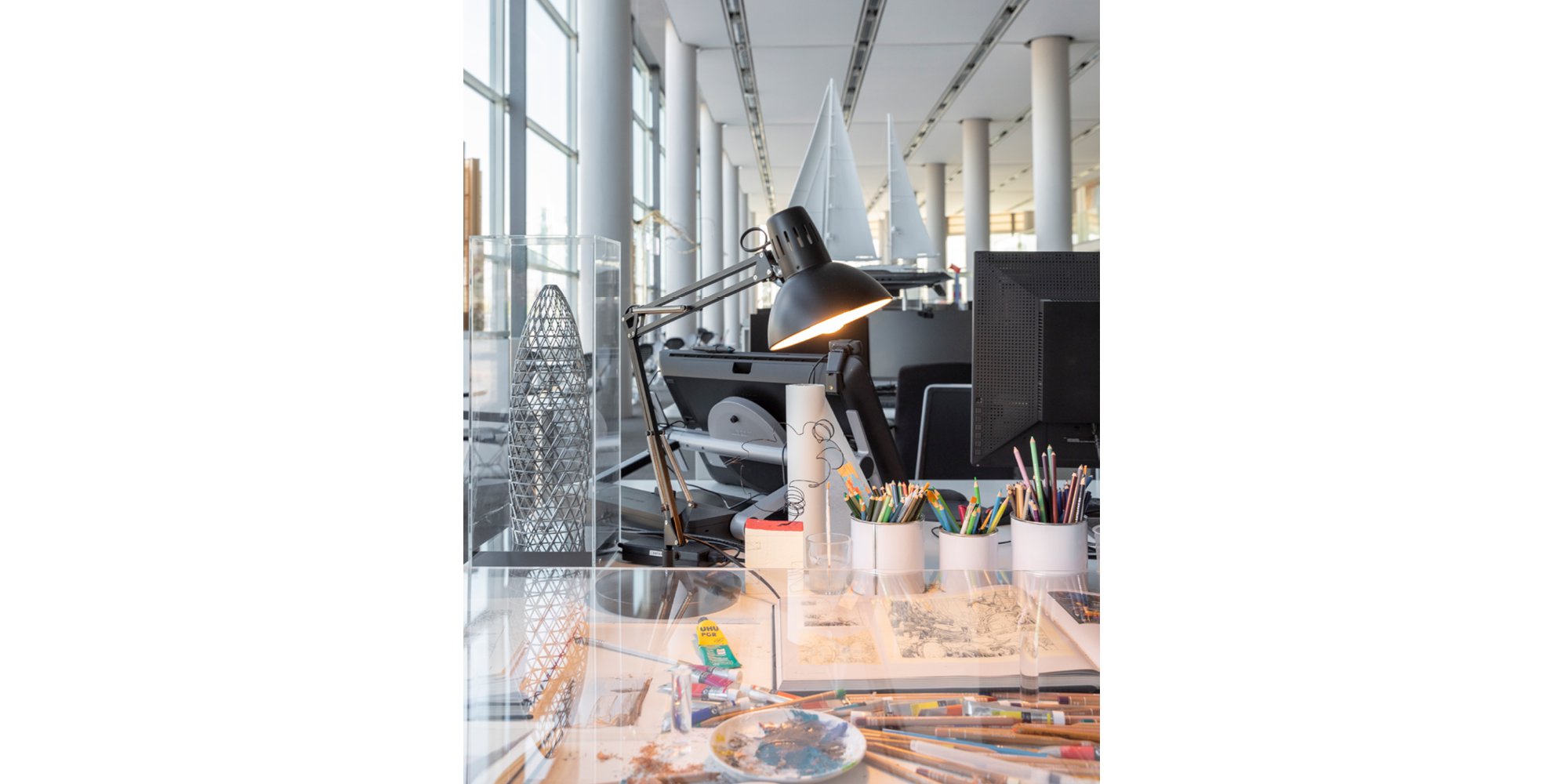

Sitting somewhat evocatively between – and in service of – these two polarities (the concept sketch and the as-built plan) is the work of the Design Communications team. The group, founded by Narinder Sagoo in 2001, are a collective of specialised designers who offer a range of technical skills across artistic and architectural disciplines.

The team are not a substitute for the drawings or design processes of the architects. Technical drawings configured by the designers, the diagrams calculated by engineers, or the detailed renderings developed in games engines within the visualisation teams – not to mention the plans shared with contractors, legislators, or the public – are all types of drawing that are equally fundamental to Foster + Partners’ daily life. Rather, Design Communications is a team that evolved from, and remains intrinsic to, this ingrained culture of draughtsmanship.

Alongside other ongoing activities of drawing in the practice, the team gear themselves towards the more narrative-driven stage of a design by using a range of complimentary mediums and skillsets to tell a story. Their position alongside architects, engineers, and visualisation teams not only affirms the continued vitality of drawing throughout the Foster + Partners studio but also celebrates the joy and freedom that drawing has to offer. Whether an early rendering of mood or suggestion of space, or a fully realised visualisation, the impulse is the same: to, as Narinder puts it, ‘humbly and curiously question what might be possible.’

The Possibilities of Architectural Drawing

The effectiveness of architectural drawing has endured – despite the numerous academic, philosophical, and (more recently) digital revolutions that have routinely promised to perfect and override it. From the guidebooks on drawing developed in Renaissance classrooms, to the works of draughtsmen throughout the twentieth century, to 2D, and then 3D CAD (Computer-aided design) that we see today: the history of the architectural drawing is a history of how space has been theorised and imagined.

Within this field, an extraordinary range of avenues present themselves – from the mathematical and perspectival, to the abstract and playful – though perhaps a useful starting point is that architectural drawing is a visual representation of a creative idea. As the varied output of a studio like Foster + Partners illustrates: a highly technical, elaborate plan is as much a form of architectural drawing as the freehand, rapid sketch of that same completed presentation.

For nearly sixty years, the practice has drawn – formally or informally, individually or collaboratively – to communicate ideas within, across, and beyond all stages of a design. How, then, to evaluate or even compare such a wide gamut of what all might accurately be described as ‘architectural drawings?’ Should we? Better perhaps to offer focus on intention rather than style – in this case we are exploring the imaginative output of the Design Communications team, where drawing is a tool in service of a new idea and, as architectural historian Robin Evans suggests, is both ‘transitive and communicative.’

Drawing at Foster + Partners

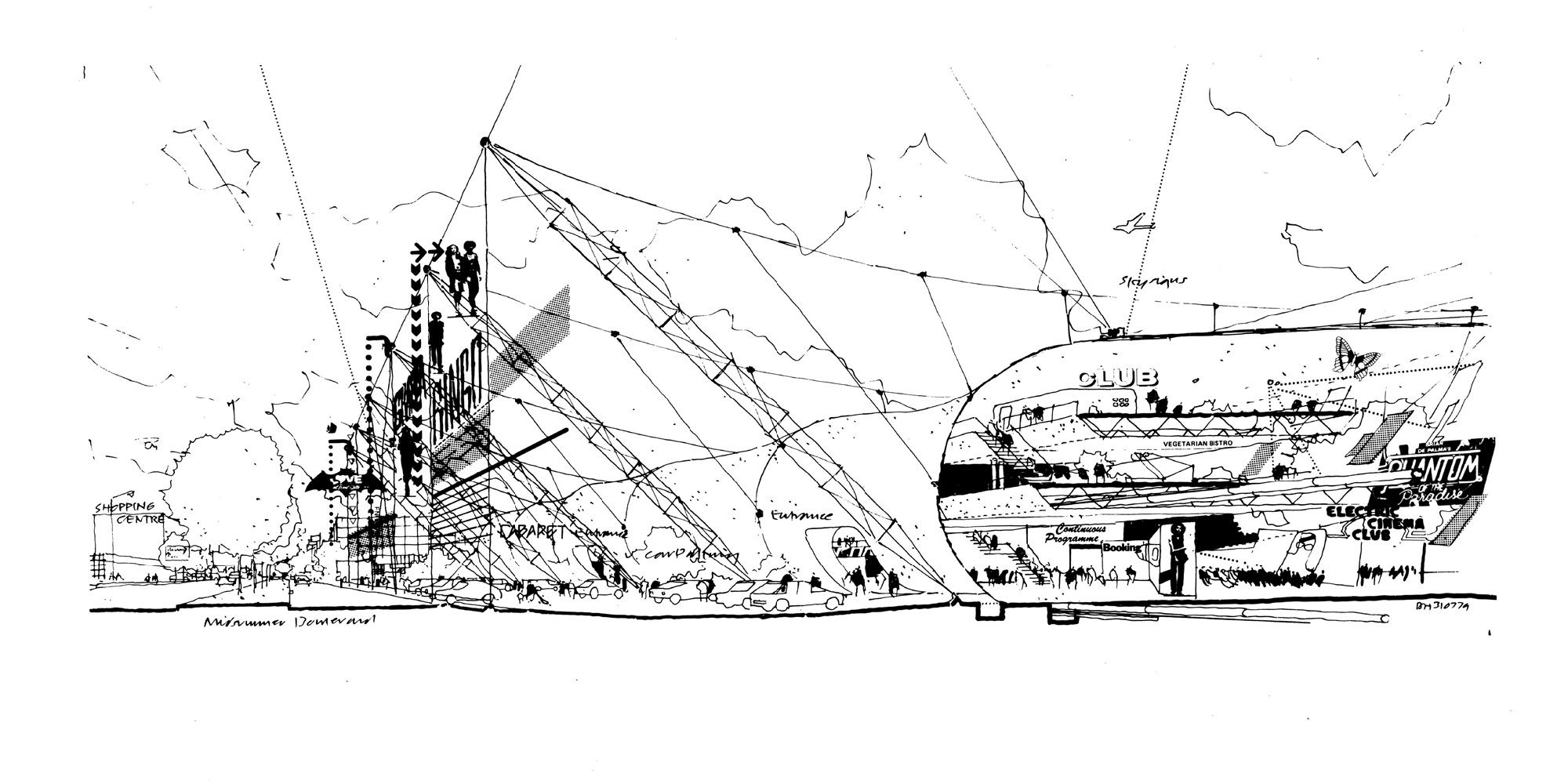

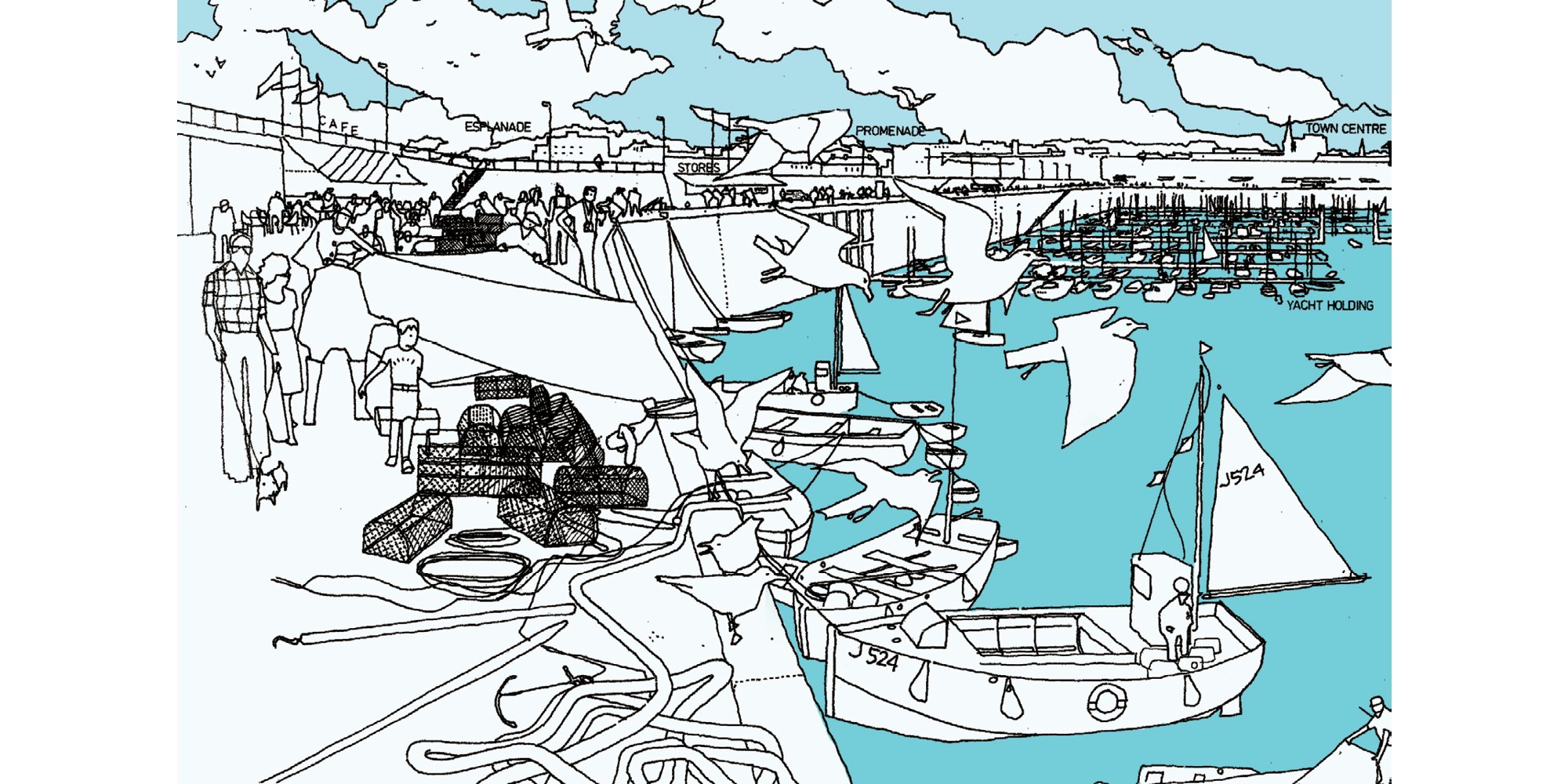

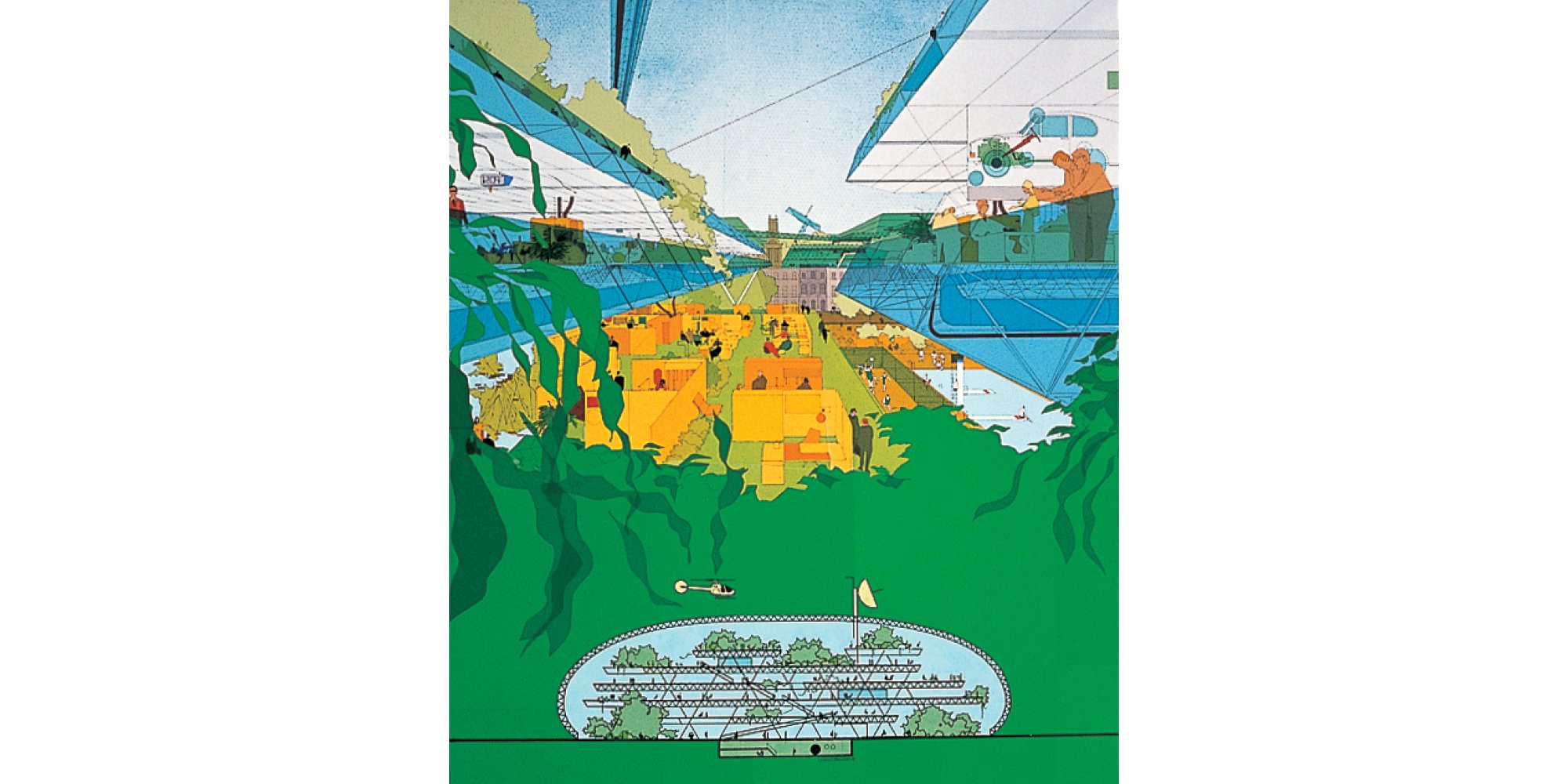

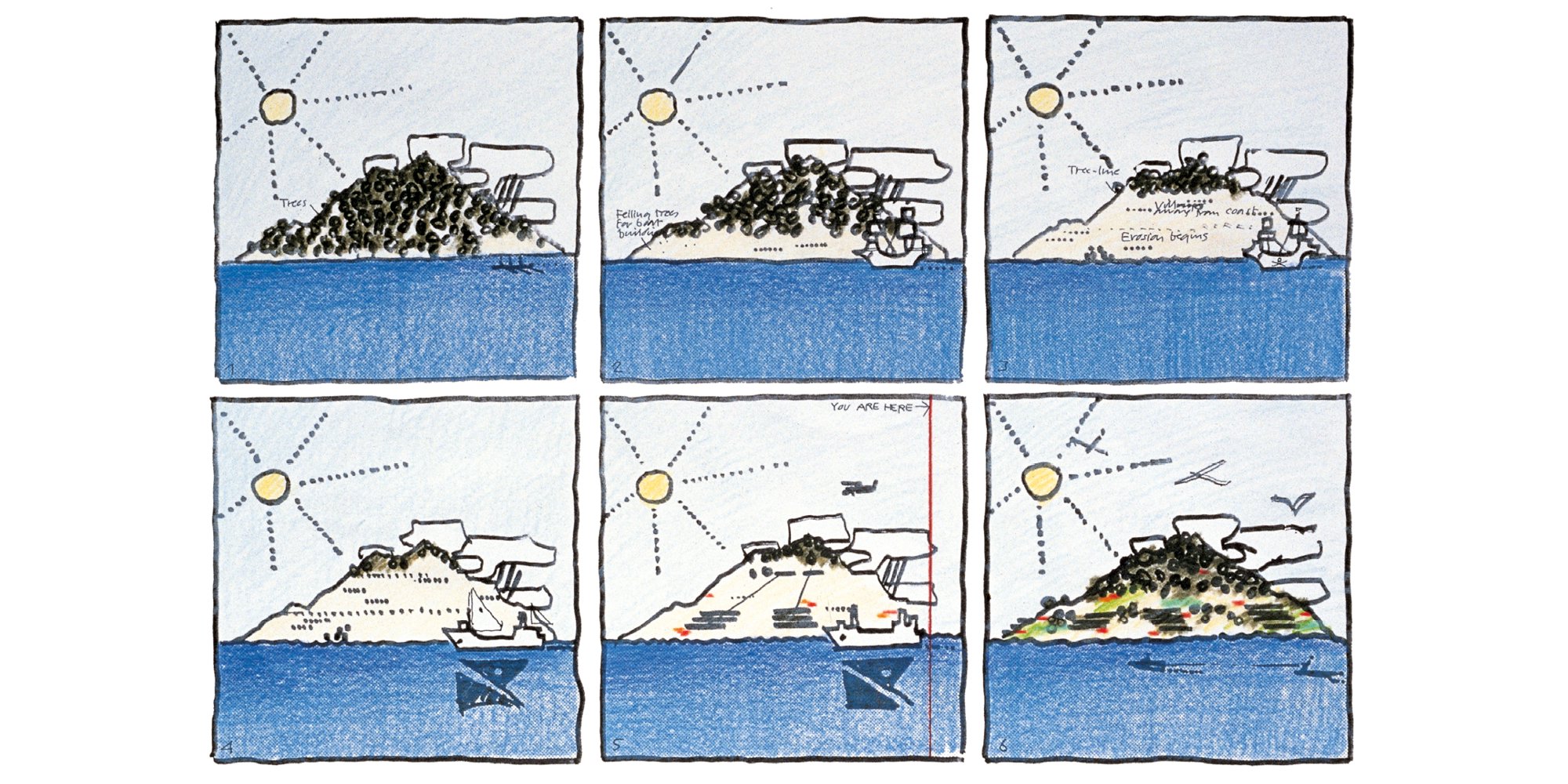

As the practice grew throughout the decades its pool of accomplished architects grew. One such architect, an influential partner in the formative years of Foster Associates, was Birkin Haward. Haward was a key member of the design team of some the studio’s most notable early projects, from the Hackney Special Care Unit (London, UK, 1972) to the Gomera Regional Planning Study (Canary Islands, Spain, 1975). In support of his talents as an architect was Haward’s now well-recognised skill as an artist and architectural illustrator – one able to switch from narrative story boarding (as at Gomera) to impressively legible technical drawings (like those produced for the IBM Pilot Head Office at Cosham, UK, 1971). Establishing his own architectural practice with Joanna van Heyningen in 1983, Haward – now a professional artist – has retained the virtuosity for communication and the visual arts that the practice was so fortunate to benefit from in those first decades.

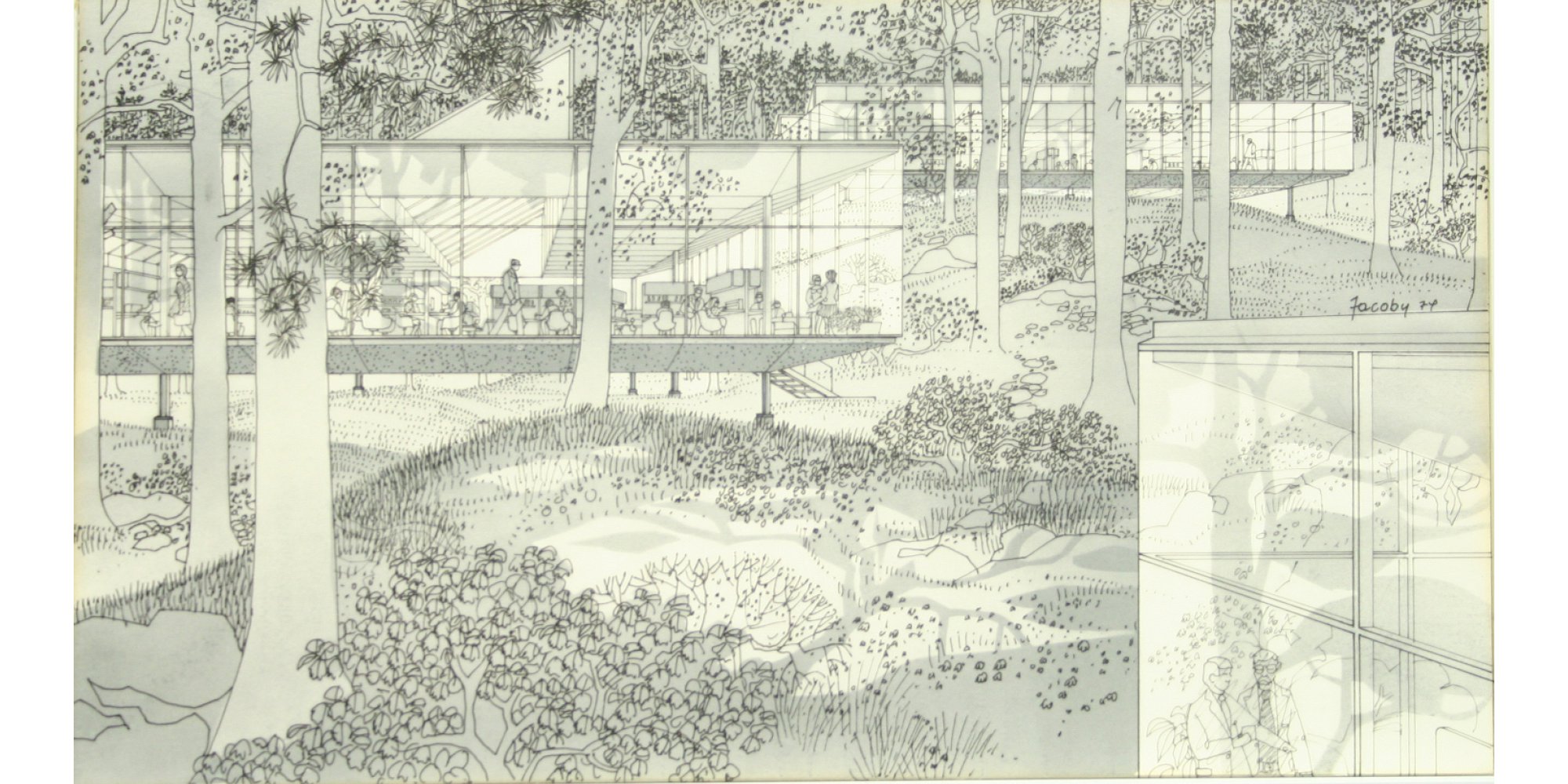

Haward is perhaps the best recognised of the architects inculcated by the practice who were also supremely talented artists and illustrators. Others, like the Czech-born architect Jan Kaplicky, would also go on to establish successful practices – Future Systems in Kaplicky’s case – and contribute to the rich legacy of drawing that the studio’s current practitioners are able to draw from. Foster Associates also sought out and commissioned works from specialist architectural illustrators, like Helmut Jacoby, who worked alongside the practice’s design teams to offer visual representations of designs. Archives of all of these drawings act as time capsules for those design processes, and, to this day, can communicate projects that were never built. Architects throughout the studio are continuing this legacy, from Senior Partners free-hand sketching construction details to new architects extolling innovative techniques in the studio’s annual Graduate Show.

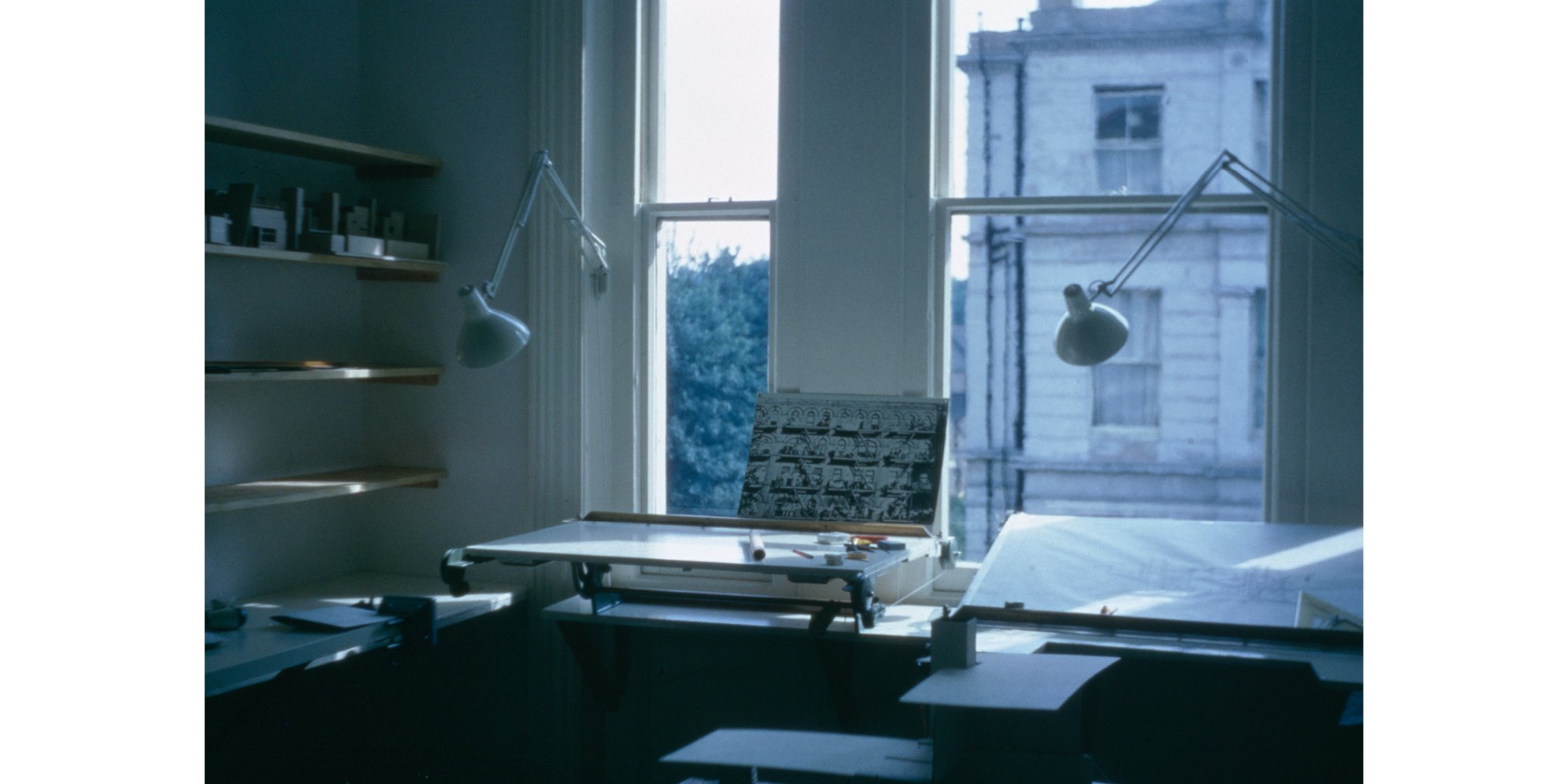

Drafting tables set against the window in the original Foster Associates office in Hampstead Hill Gardens, London - the apartment of Norman and Wendy Foster (1967-1970).

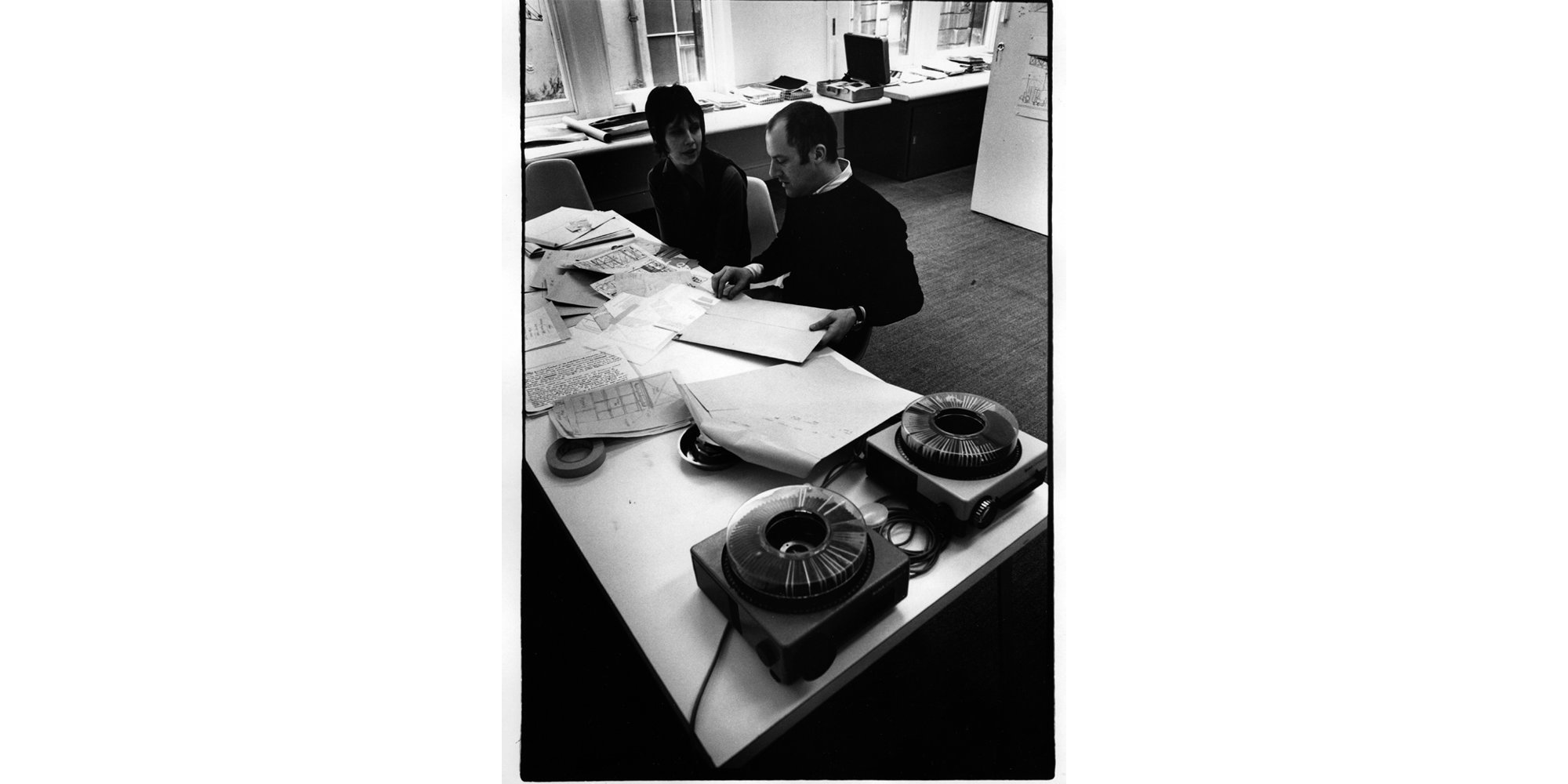

Norman and Wendy Foster review drawings in the Covent Garden studio in Bedford Street, 1970-1971.

An architect at the drafting table - part of the Herman Miller action-office system - in the Fitzroy Street studio, 1971-1981.

For their next studio, on Great Portland Street (1981-1990), the practice developed its own prototype desking system, which could tilt to the desired angle of a drafting table. This system would go on to influence a custom range for the Renault Distribution Centre (Swindon, UK, 1982) and the Nomos furniture system for Tecno (1986).

An elevated view of Foster + Partners main studio at its Riverside offices in Battersea (1990). Photographed soon after the practice moved in, the long worktables are still free of computers.

Drawing by Birkin Haward for the unrealised Granada Entertainment Centre. © Birkin Haward / Foster + Partners

Drawing by Birkin Haward for the unrealised St Helier Harbour Masterplan, Jersey, Channel Islands. © Birkin Haward / Foster + Partners

Drawing by Birkin Haward for the Climatroffice, a project that evolved from a discussion between Norman Foster and Buckminster Fuller during a break in a work session on the Samuel Beckett Theatre, Oxford. © Birkin Haward / Foster + Partners

By the twenty-first century, Foster + Partners had successfully anticipated and adapted to the ‘digital turn’ in architecture by integrating cutting-edge CAD and BIM (Building Information Modelling) technologies into the design process. However, this does not mean that the former artistic or analogue ways of representing space were superseded and lost; drawing at Foster + Partners remains a particularly hopeful and versatile form of architectural representation that is both predicated on, and adjacent to, the projects that the practice design.

Sketches by Norman Foster. Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, UK (1978). © Norman Foster Foundation

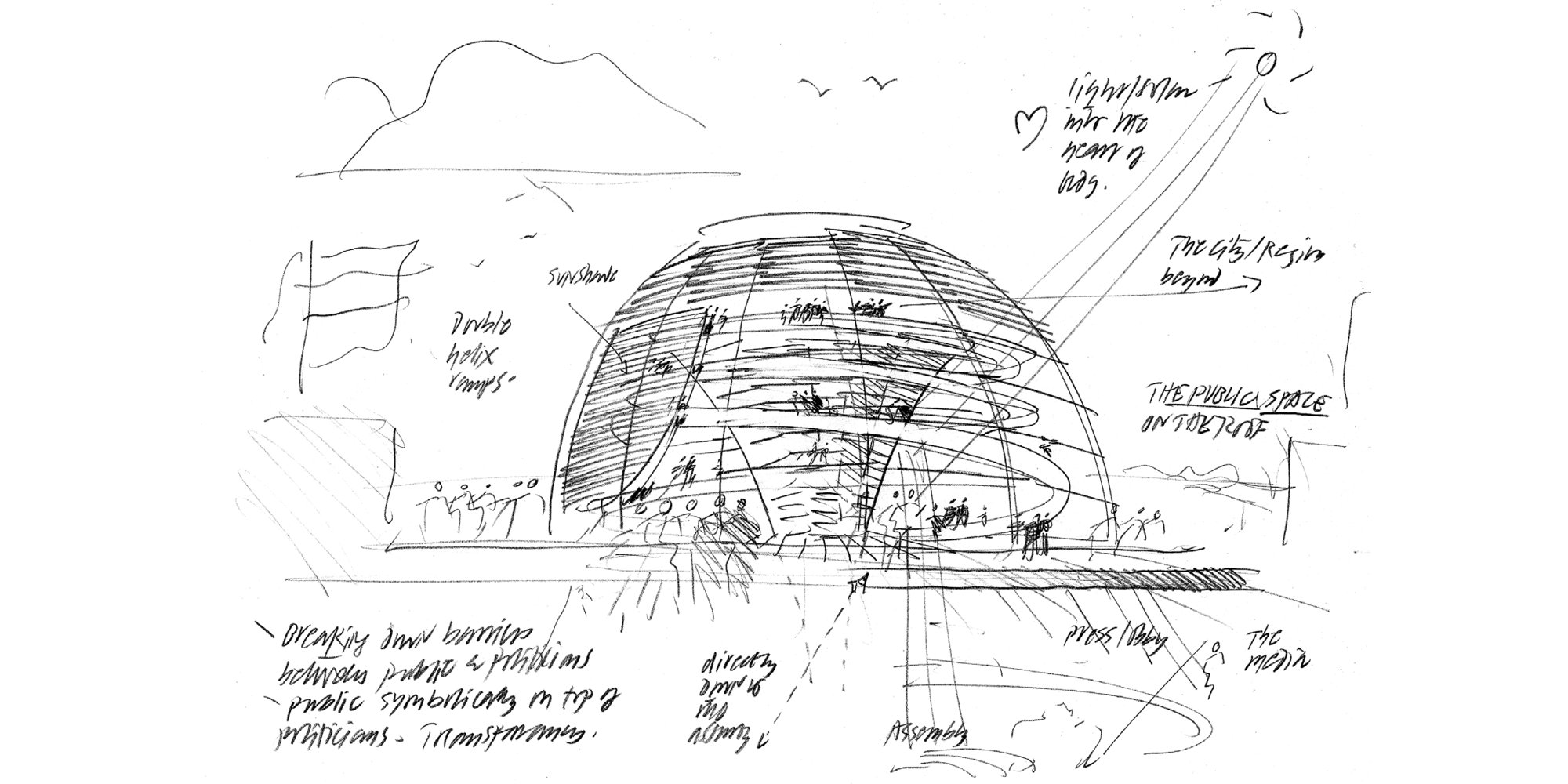

Sketches by Norman Foster. Reichstag, New Parliament, Berlin, Germany (1999). © Norman Foster Foundation

Understanding its value for both architects and clients across analogue and digital forms, Foster + Partners has committed an entire department to the unique and invaluable process of drawing. For a global practice that works across languages, drawing remains a reliable tool to communicate ideas quickly and clearly.

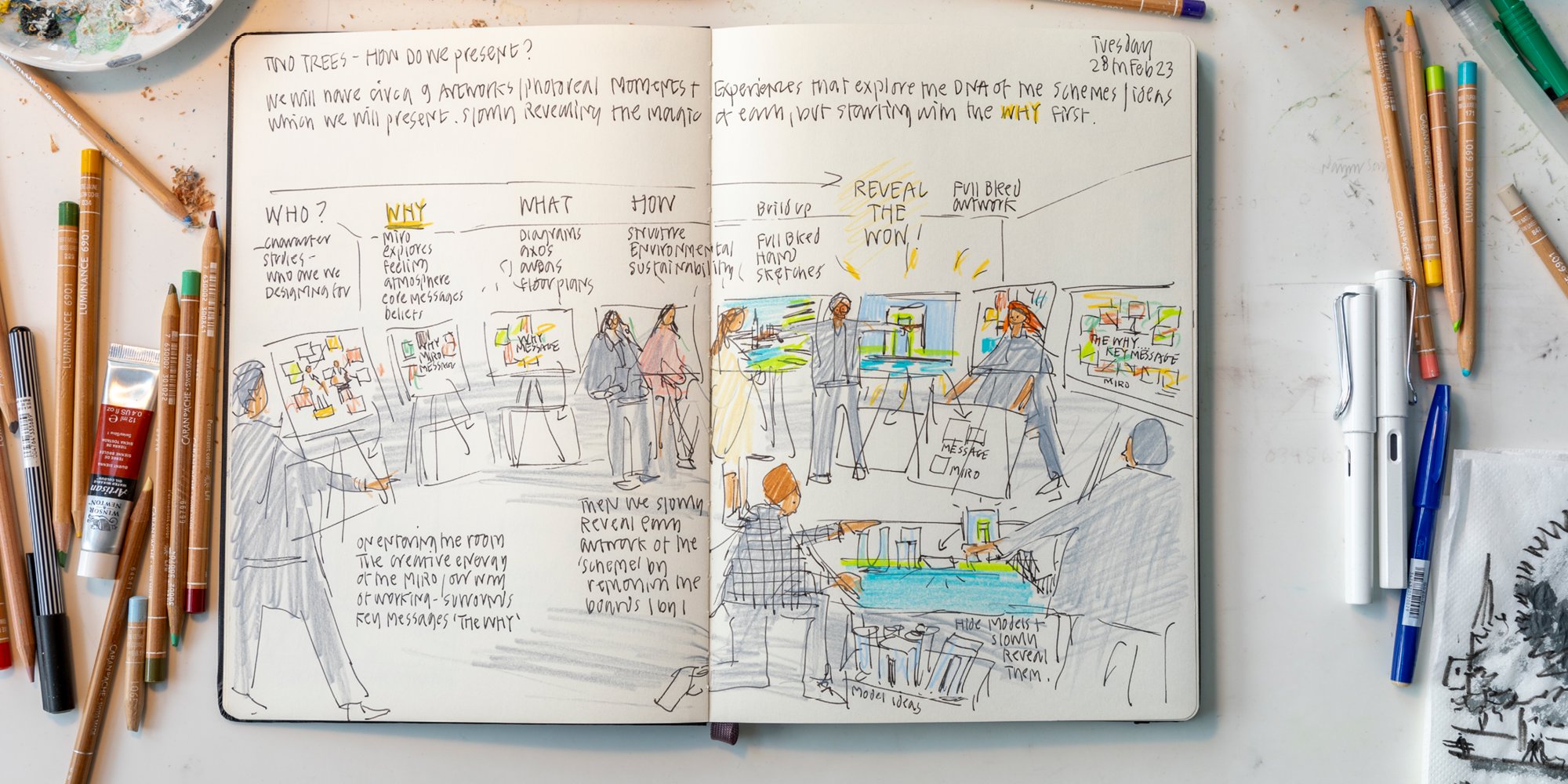

Design is not Linear

The Design Communications team operate according to a culture of ‘creative democracy’ that allows for the non-linear, non-hierarchical exchange and transformation of ideas. Working in the same studio space, ideas can develop simultaneously and in awareness of one another. This approach seeks connections, resonances, and perhaps even points of departure across mediums. This is not only reflected in the spatial configuration of the practice but also in the detective-style boards that the team use, which make tangible the often-intangible process of design, the ‘complex affair’ between problem and solution which Bryan Lawson likens to ‘a crossword puzzle.’ However, unlike a crossword puzzle or a detective novel, a design does not readily admit to being ‘solved’ in a single way. Perhaps this is why Richard McCormac, former head of the RIBA, described design (of which drawing is a key aspect) as ‘the least understood intellectual skill in the building industry today.’

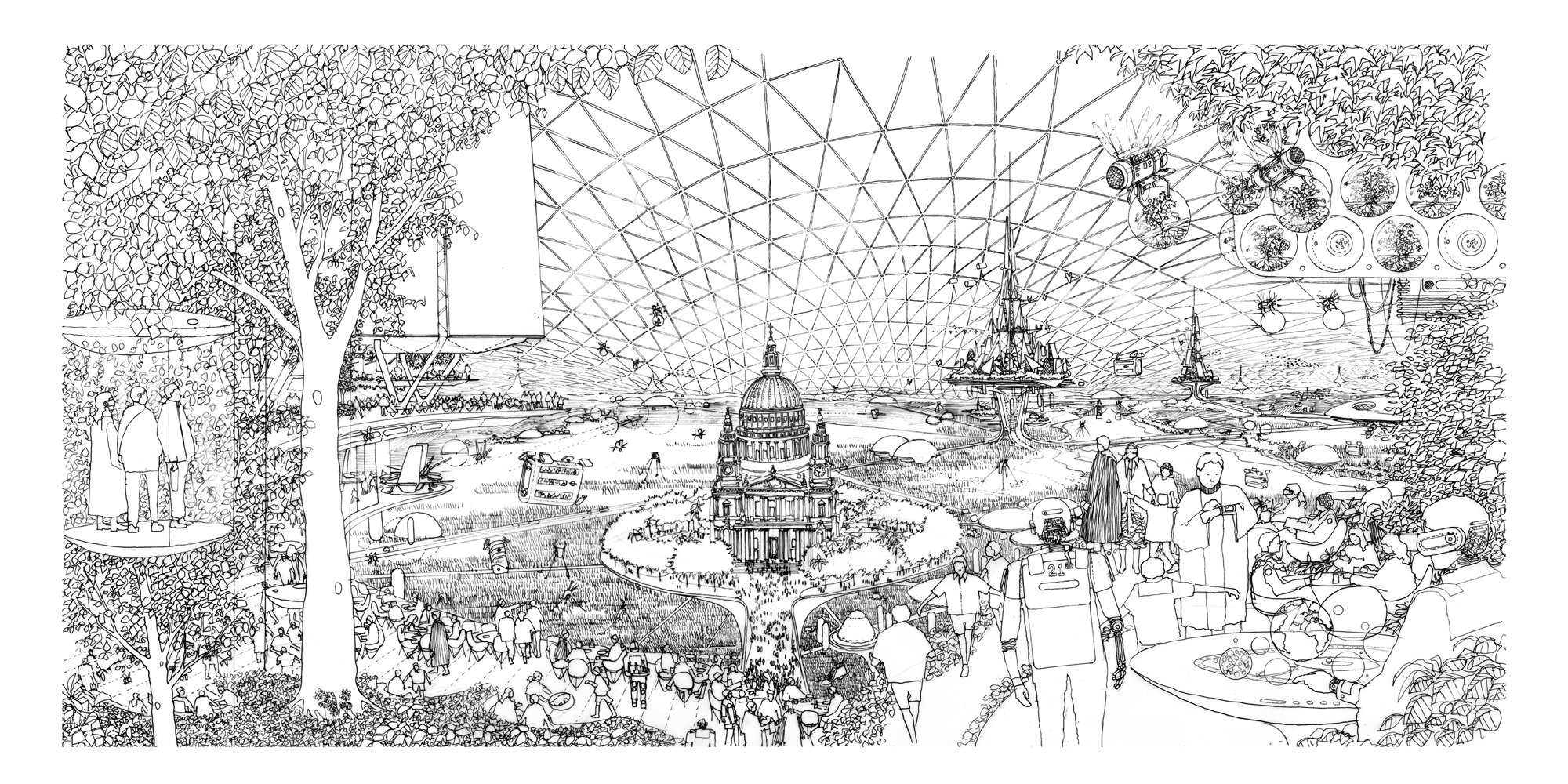

'The City of the Future' imagined by Narinder Sagoo. © Narinder Sagoo / Foster + Partners

Public realm eye level handdrawing of 30 St Mary Axe (London, 2004) by Narinder Sagoo. © Narinder Sagoo / Foster + Partners

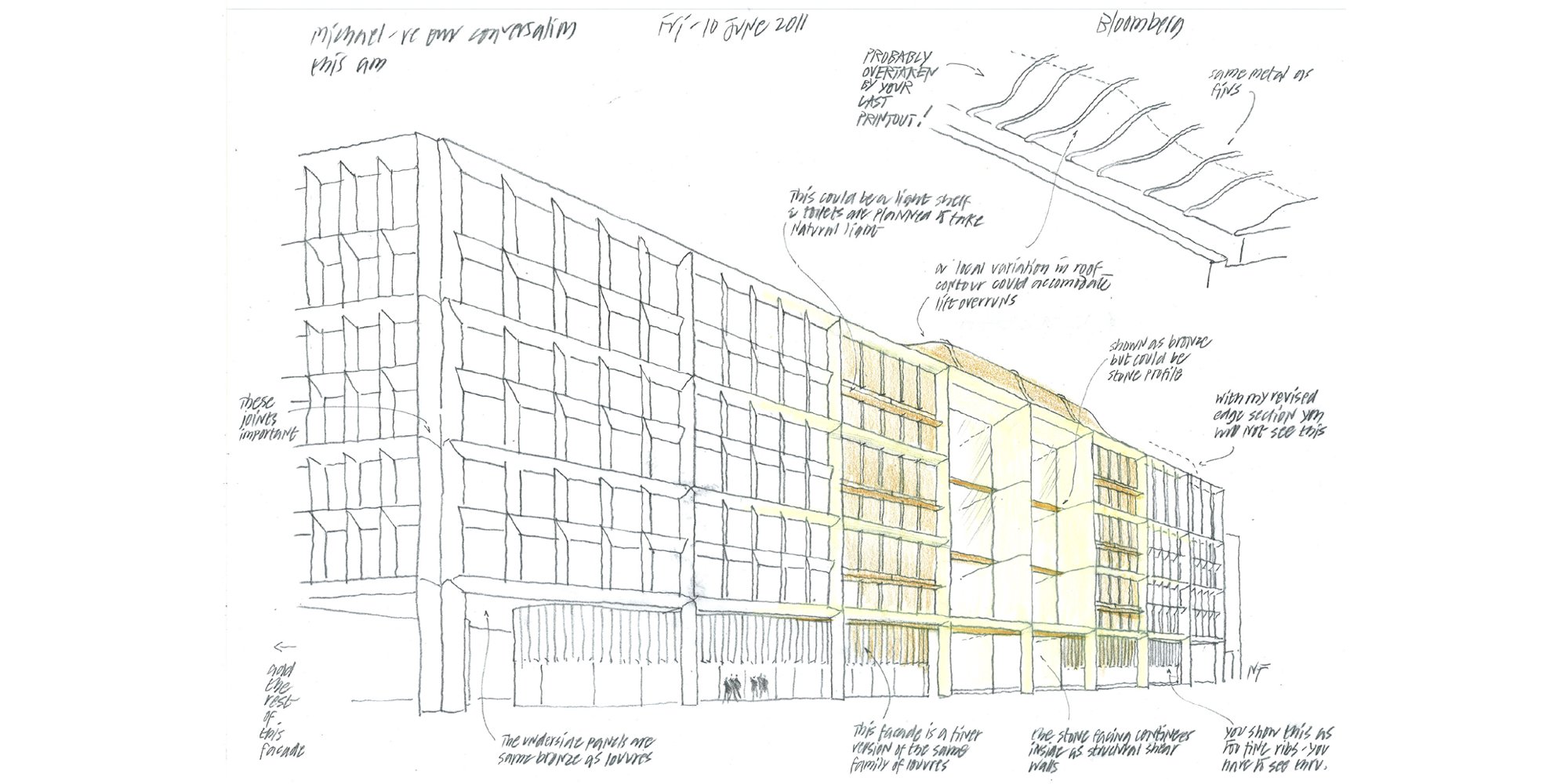

The team are often (though not exclusively) brought into projects to visually communicate and perhaps even help steer a design as it develops. They respond to projects with an impressive range of drawing materials and techniques. As Narinder explains, ‘different speeds and tools suit different intellectual and emotional processes.’ The seemingly small act of switching from a pencil to a pen – or between pens of different point sizes – has significant consequences on the work produced. Shifts between analogue and digital techniques, as well as the introduction of animation and acoustic components to a working definition of ‘drawing’, have further diversified the field. One client might appreciate an impressionistic concept sketch that colours the mood of a site. Others might prefer a photorealistic image that allows them to ‘time-travel’ into a project that is years away from completion. A third might not know what they want until they see it, leaving the team to decide how best to represent an idea. The team have to gauge which response would work best for the architects and clients, and at what moment within the design process to offer these responses - and avoid the common mistake of presenting a single solution too early. Design is not a monoculture; it is an ecosystem.

The Drawing Board

Architectural design is a spatial form that depends on interconnected systems and expertise. Visually communicating a design, then, requires a similar degree of interconnectedness across mediums. Jordan, Nicte, Victoria, Aurelio, and Matthew are five members of the Design Communications team (which is now around forty people) who all operate under the expansive and expanding term ‘drawing.’ As a grouping, their specialisms range from conceptual, sketch, and photorealistic artwork, through to moving art and animation. As Matthew comments:

The architectural drawing used to outline and document what a building would be. Nowadays, we have scale models and technical drawings that do this – and with extreme, millimetre precision. So what should drawing do? It imagines what a building could be.

This broadening definition does not dilute the training or attention required to draw. Each medium does have its strengths, skillsets, and practitioners. One form of drawing might be more appropriate than another at a particular stage of a design. This is the case for Jordan, who is a concept artist. Often brought in at an early stage of a design – when plans have not yet been made – Jordan works to understand the ‘mood’ or ‘atmosphere’ of the project and transform this into a sketch or digital painting. ‘The advantage of working in this painterly way means that you don’t have to nail the final details such as doorframes or lampposts… it’s about offering ideas that can open up discussions, rather than shut them down.’

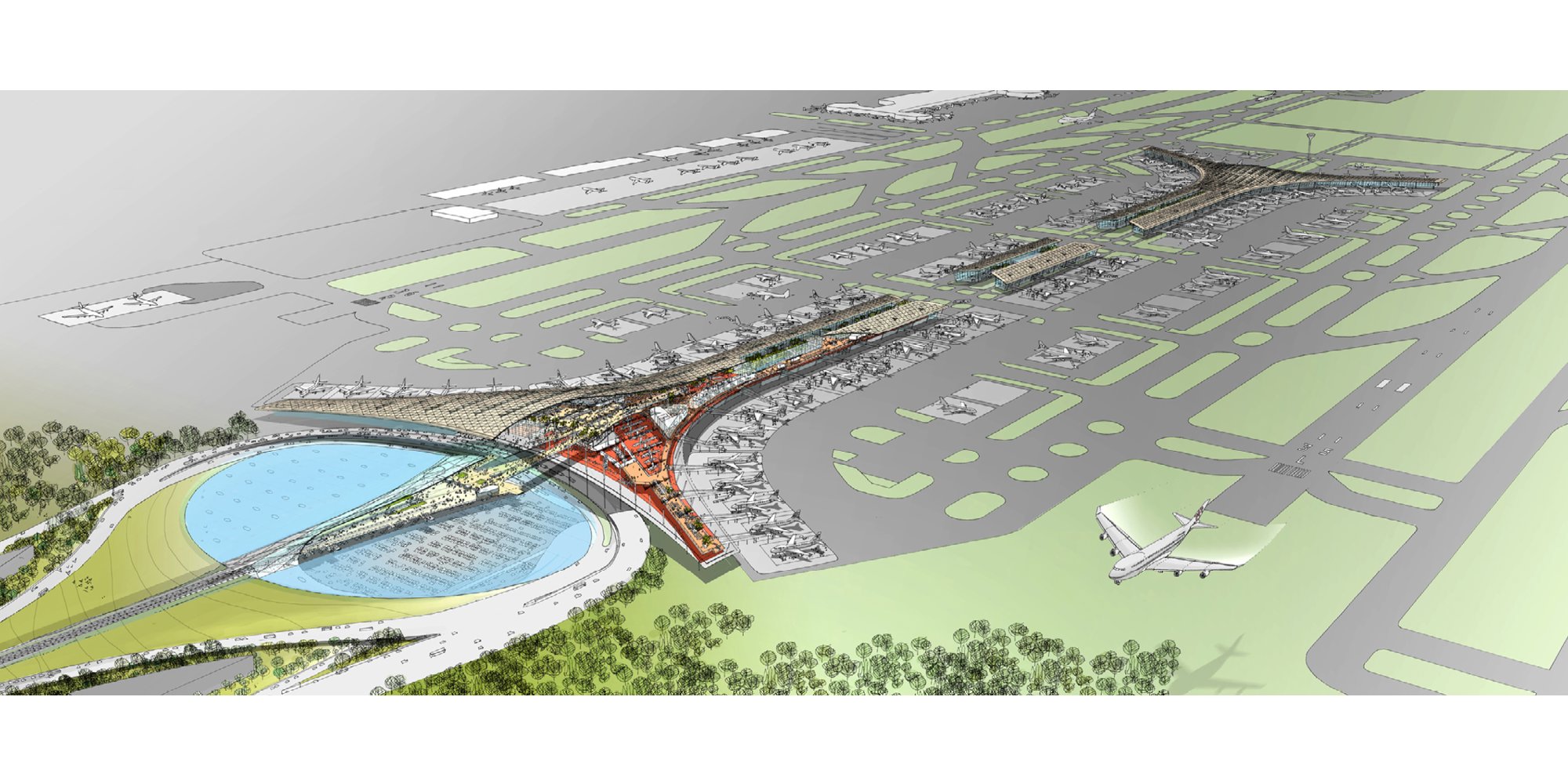

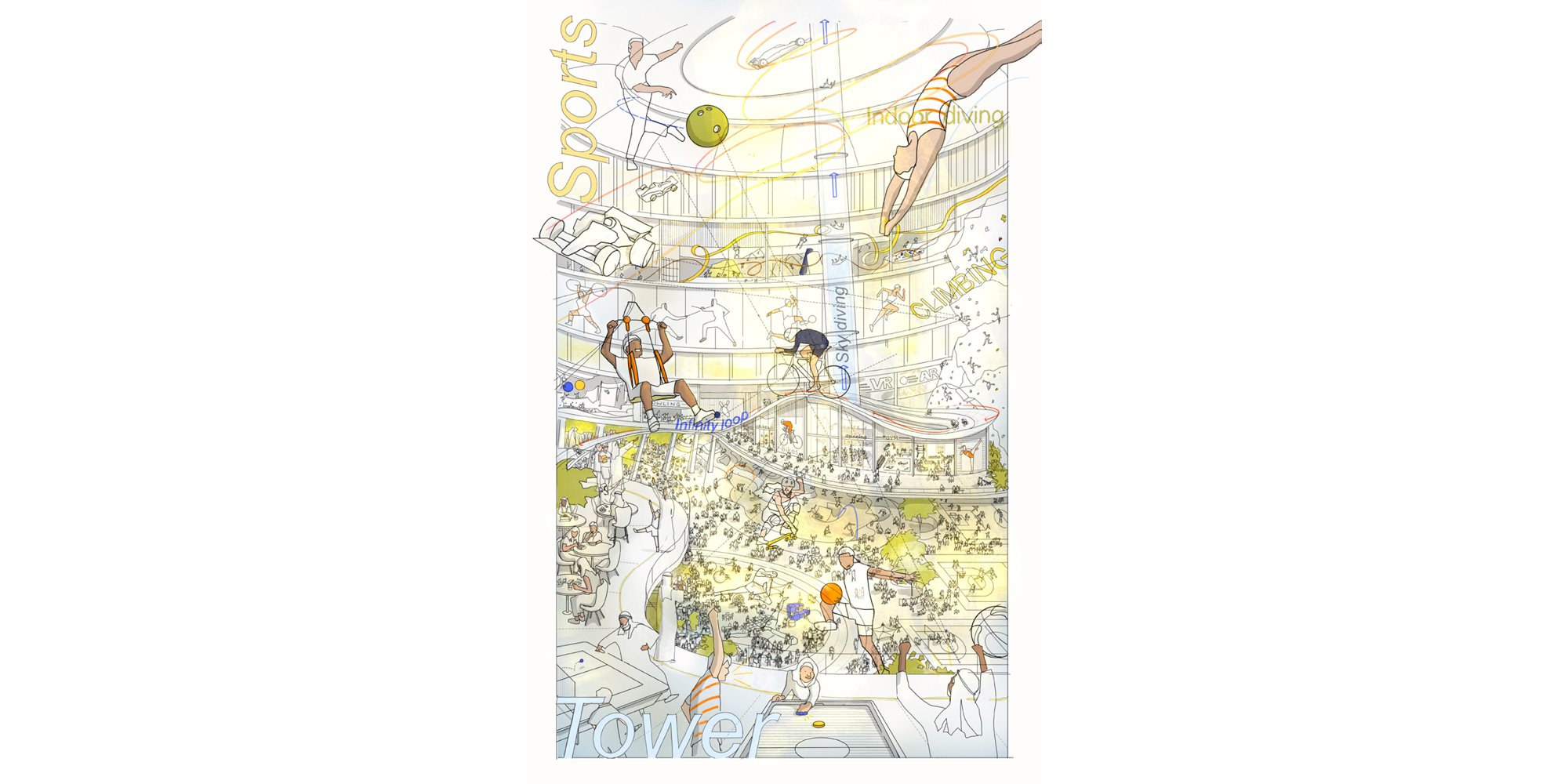

Examples of Concept Art created by Design Communications Artists, showcasing a wide range of techniques and styles to communicate a sense of mood, story and design within the early stages of projects. © Foster + Partners

Examples of Concept Art created by Design Communications Artists, showcasing a wide range of techniques and styles to communicate a sense of mood, story and design within the early stages of projects. © Foster + Partners

Examples of Concept Art created by Design Communications Artists, showcasing a wide range of techniques and styles to communicate a sense of mood, story and design within the early stages of projects. © Foster + Partners

Examples of Concept Art created by Design Communications Artists, showcasing a wide range of techniques and styles to communicate a sense of mood, story and design within the early stages of projects. © Foster + Partners

Examples of Concept Art created by Design Communications Artists, showcasing a wide range of techniques and styles to communicate a sense of mood, story and design within the early stages of projects. © Foster + Partners

Examples of Concept Art created by Design Communications Artists, showcasing a wide range of techniques and styles to communicate a sense of mood, story and design within the early stages of projects. © Foster + Partners

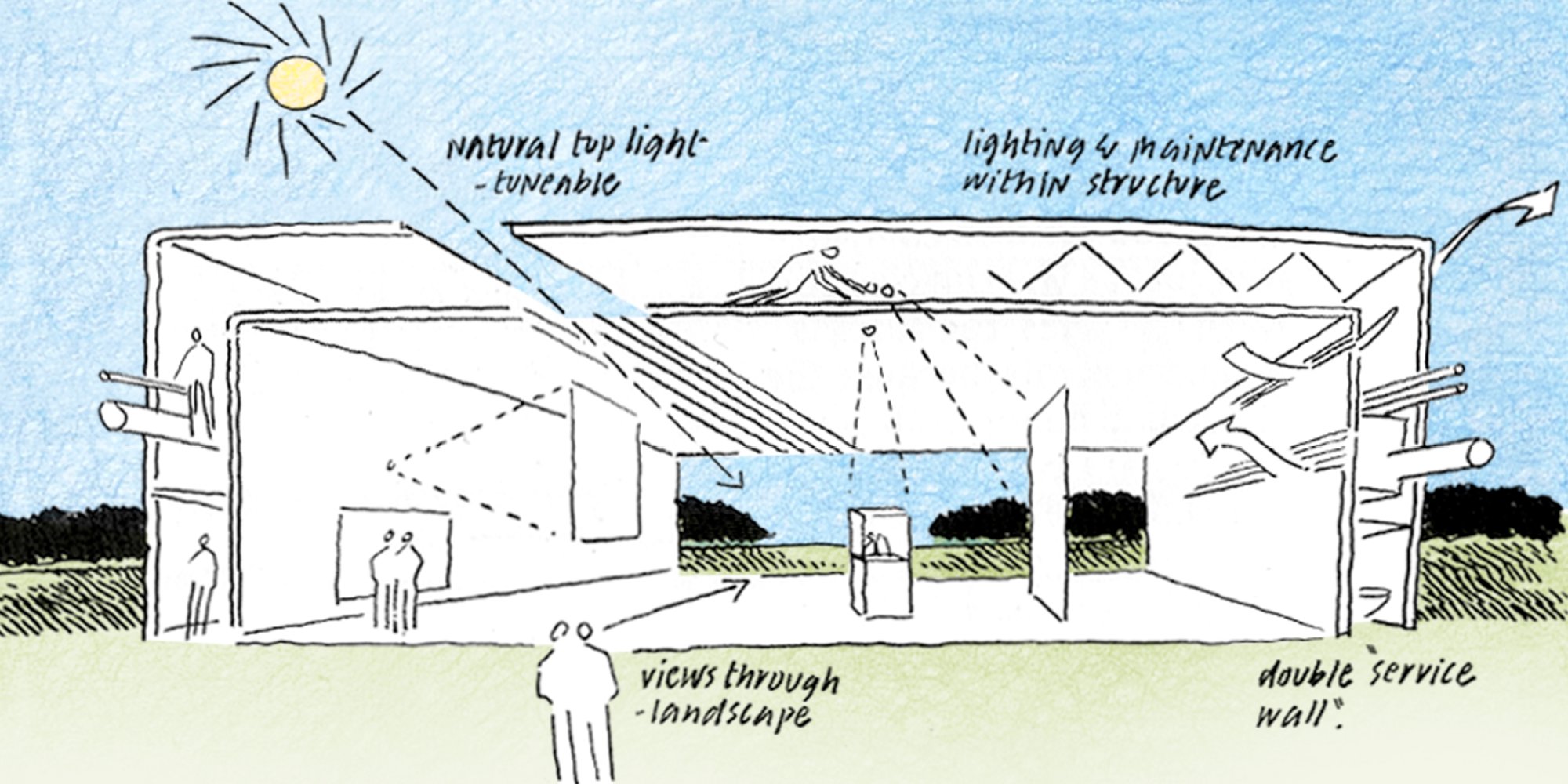

Alongside Jordan, artists like Nicte develop an initial concept drawing into a two-dimensional sketch that, in turn, might then be animated. This requires close collaboration with the architectural and urban design teams to outline plans and faithfully reproduce them in ways that are visually engaging and that begin to make sense. Nicte’s diagrammatic sketches and animations display thinking in action and are often used to demonstrate how different systems in a design might interact – that is, how a design will function. Arrows and captions, for example, are not themselves drawn to be built but are graphic tools for articulating the design that will be built. People and places can be outlined without needing to be ‘coloured in’. Movement can be gestured towards, and symbols can be used to clarify an idea. In this way, Nicte’s drawings work with a conceptual freedom that allows the processes underpinning a design to be suspended and revealed, not as a final object, but as an essential ‘working out’ step in the process.

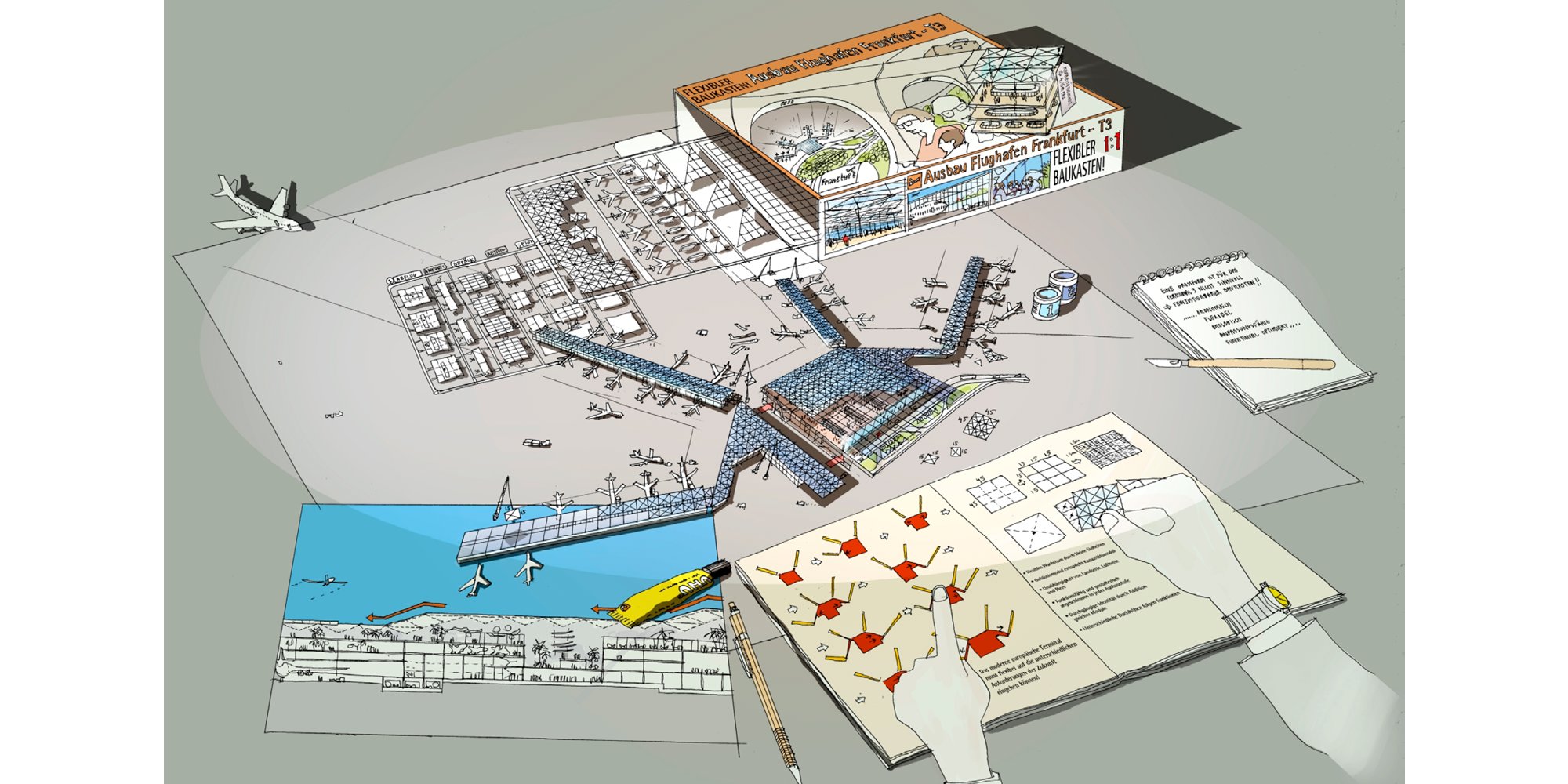

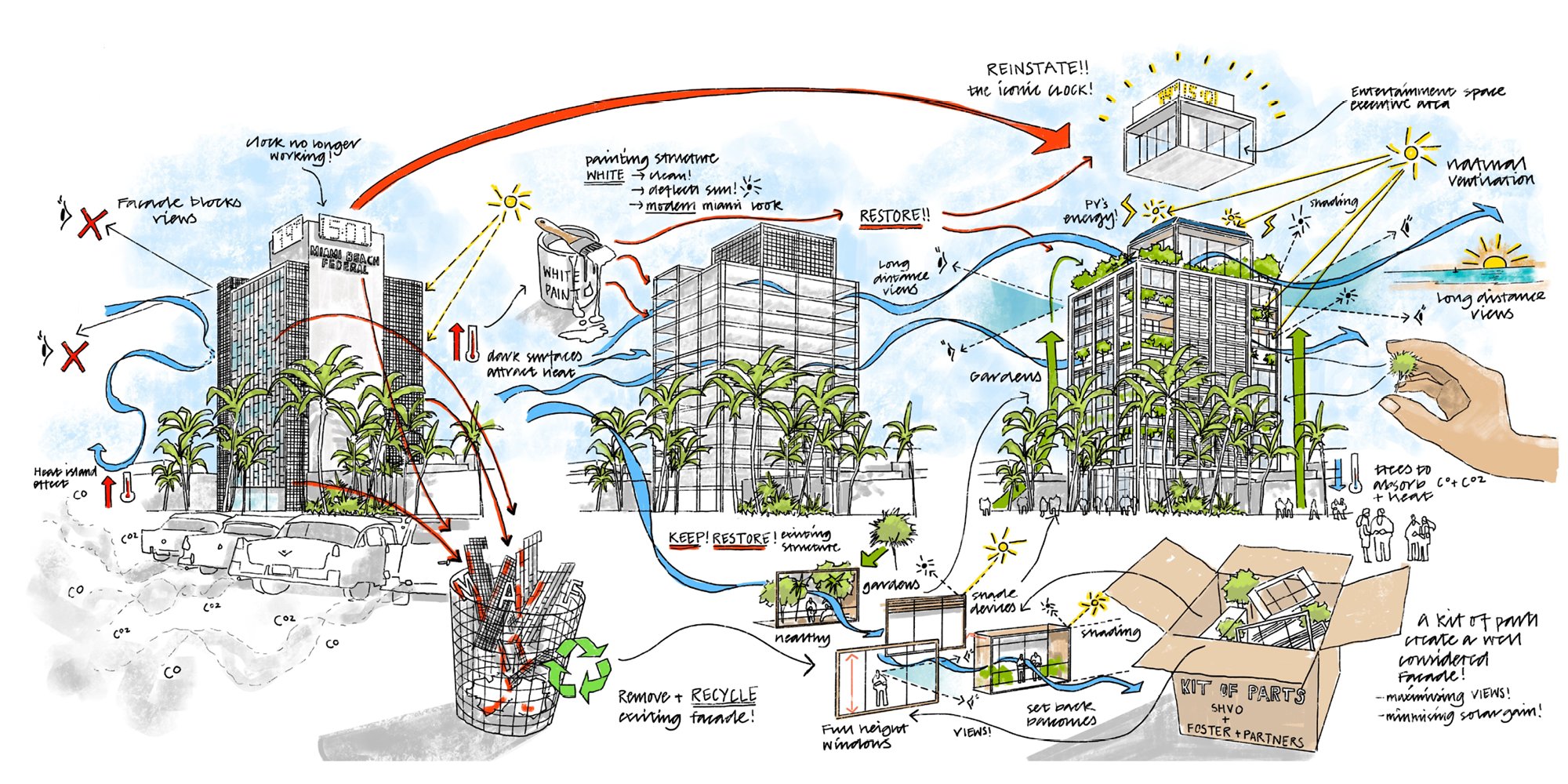

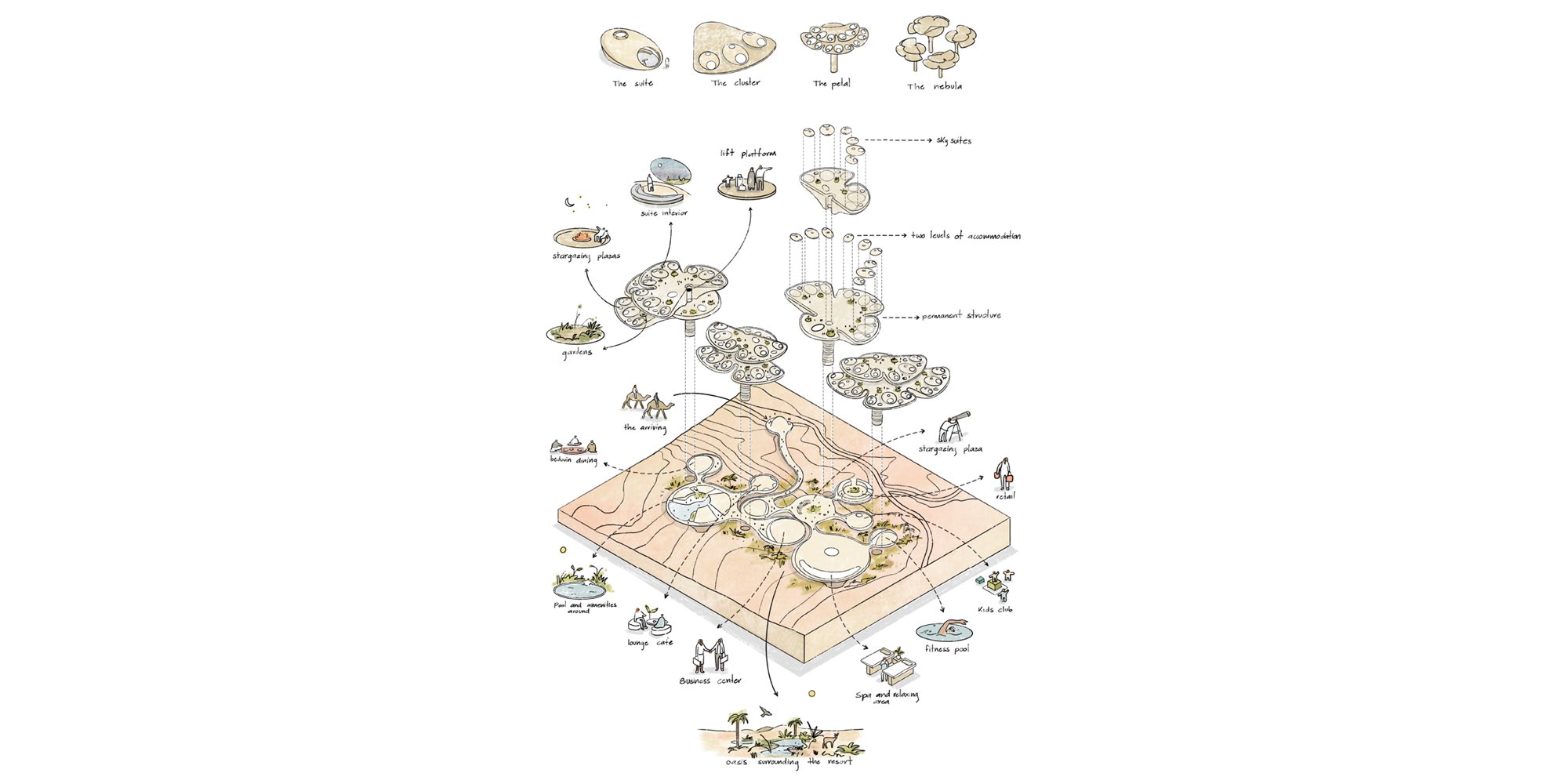

Examples of diagrammatic sketches created by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

Examples of diagrammatic sketches created by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

Examples of diagrammatic sketches created by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

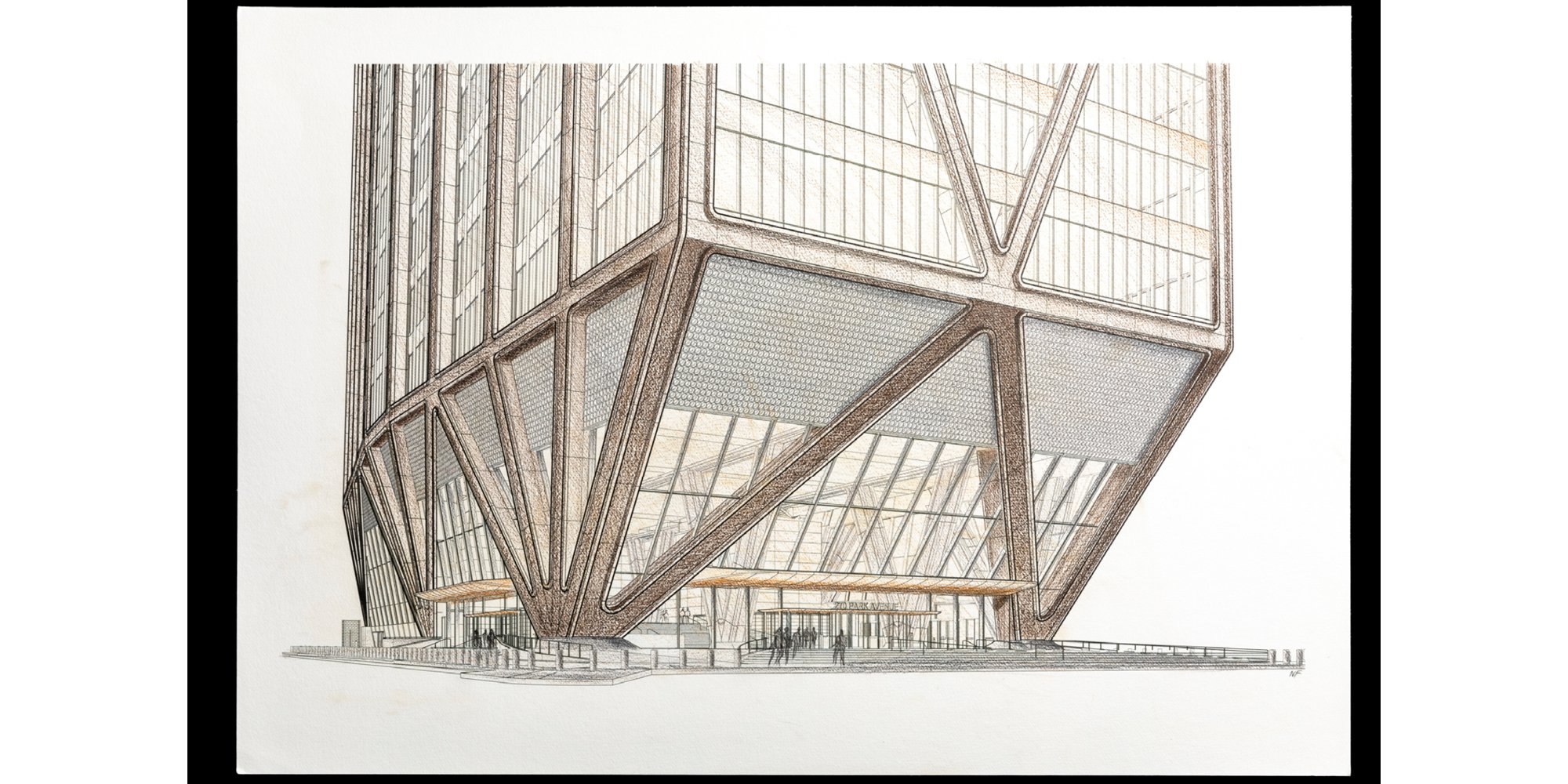

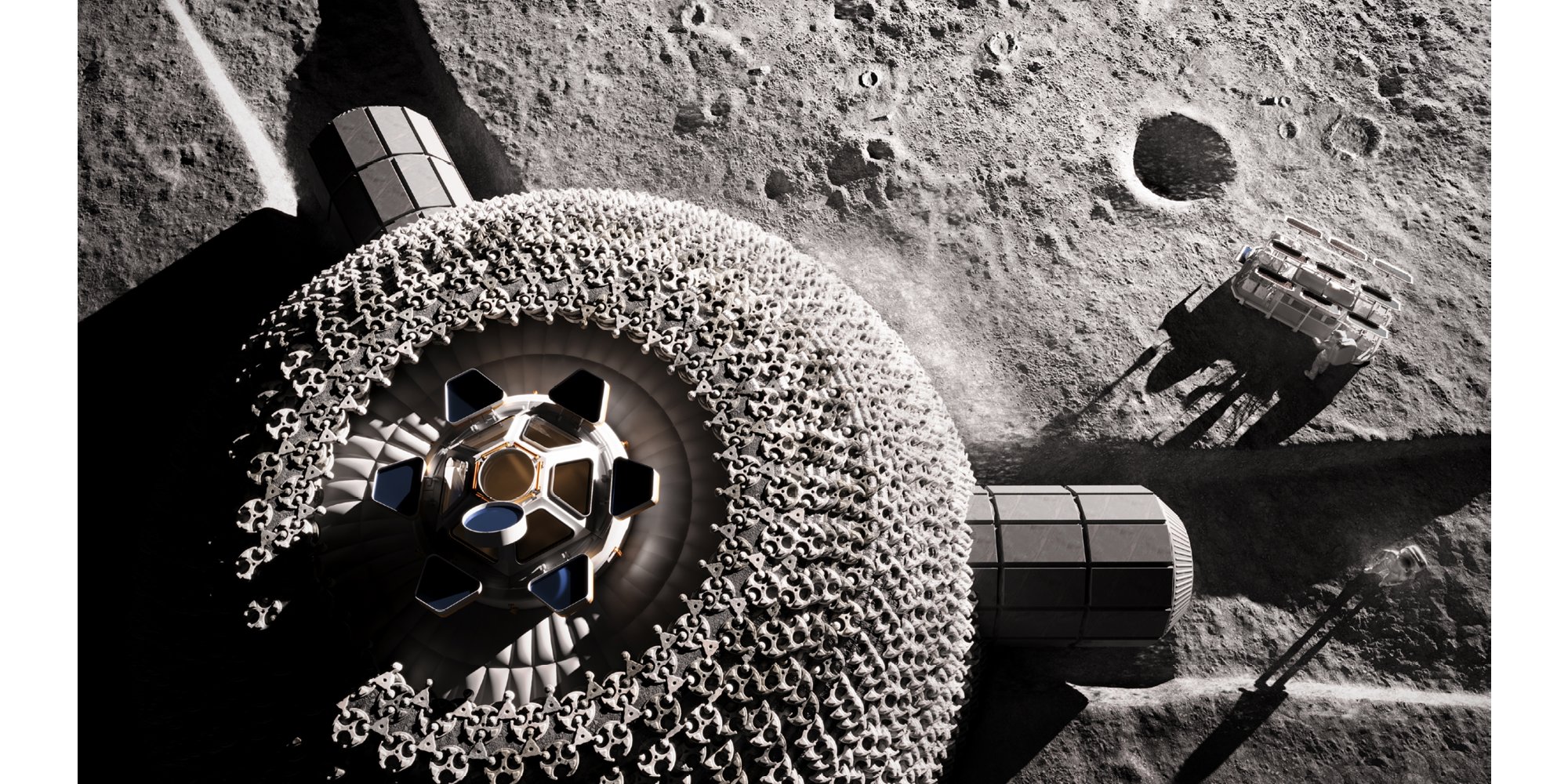

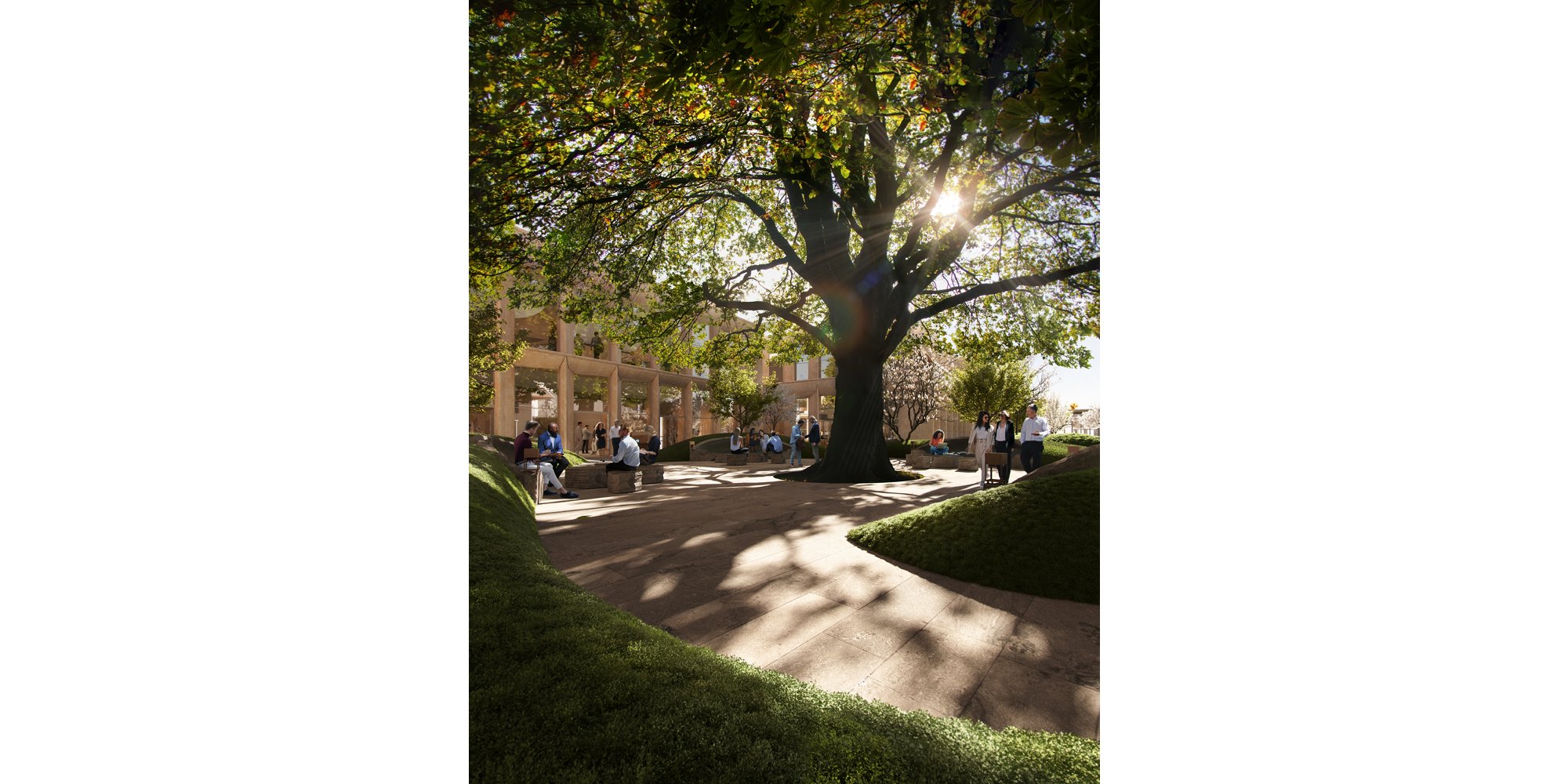

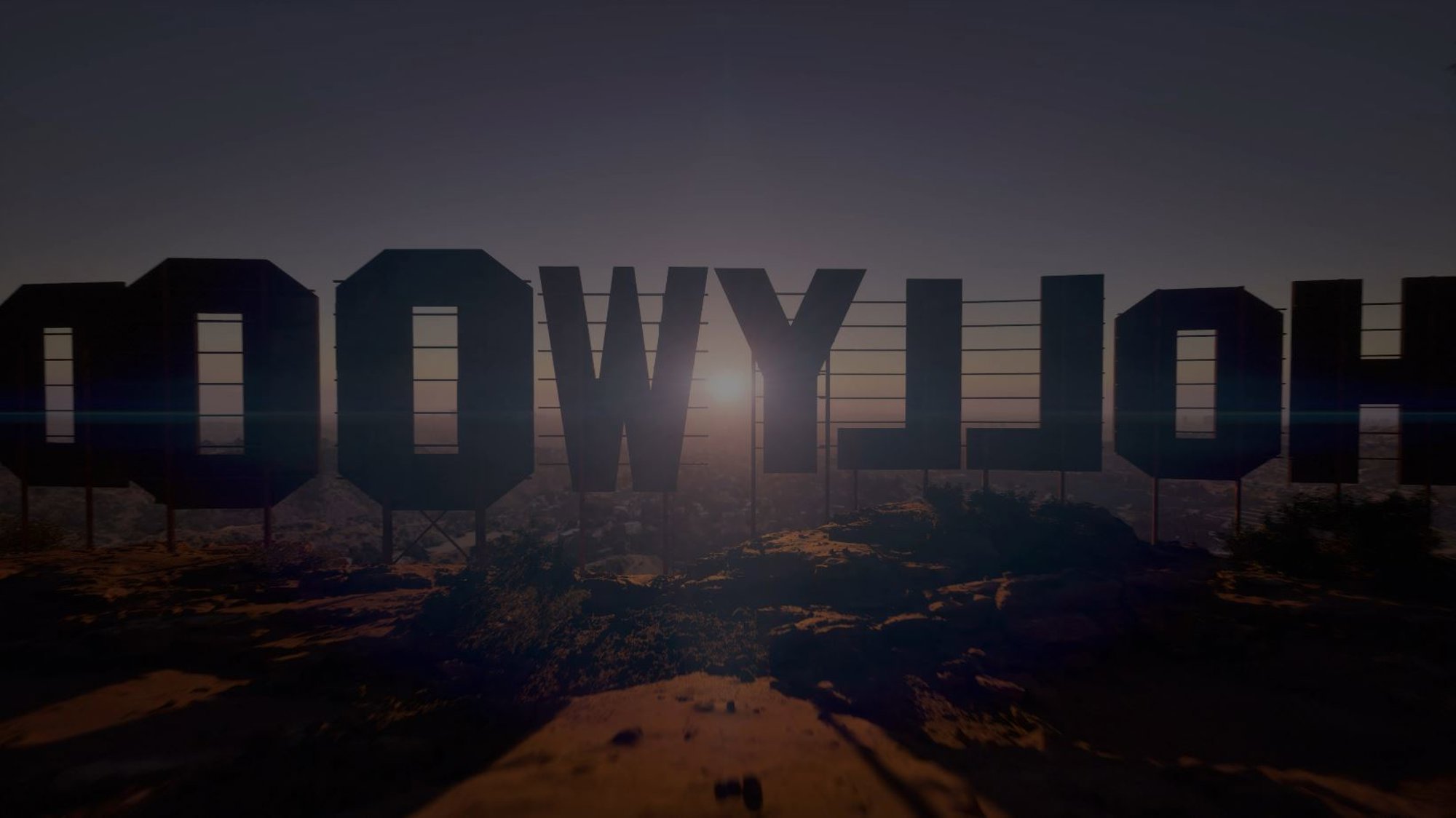

One step ‘further’ (though, as mentioned, this process is rarely linear) is a photorealistic projection of what might be possible. This medium asks: what will the design actually look like? Can we glimpse a potential end product? Victoria and Aurelio, both photorealistic artists, work closely with the rest of the team to ‘give life to the design’ through their drawings. This happens at an increasingly granular level of material textures, local vegetation, and lighting orientation. Photorealistic drawing, like concept art or moving art, must also addresses a question of atmosphere; Victoria gives the example of a stadium project, claiming that that ‘the details of the crowd and how the space is used are equally, if not more, important as the technical aspects of the design.’

Examples of photorealistic imagery created for a range of projects by the Design Communications team. Above, the Lunar Habitation, a project made in collaboration with the Specialist Modelling Group. © Foster + Partners

Examples of photorealistic imagery created for a range of projects by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

Examples of photorealistic imagery created for a range of projects by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

Examples of photorealistic imagery created for a range of projects by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

Examples of photorealistic imagery created for a range of projects by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

Examples of photorealistic imagery created for a range of projects by the Design Communications team. © Foster + Partners

In this photorealistic medium, questions of possibility (that are always present in a drawing) become increasingly pertinent. Is what is being built probable or realistic? As Victoria notes, ‘images like ours are important for winning competitions, and they are one of the best and most succinct ways to communicate a design.’ But such images, in the broader architectural field, are often installed with anxieties about making false promises long before the foundations have been dug. As ironically suggested by architectural photographer John Donat with the question ‘Why does it never rain in The Architectural Review?’ architectural imagery can often be idealised, void of people and context. As Aurelio adds:

We are very aware of avoiding propagandistic views and making claims that can’t be met. Part of this is avoided because many of us have architectural training, and we work closely with the architects at every stage of the process. So we can look at an image and know, at a functional level: “This won’t stand up, that’s not possible.”

Drawing in this way requires a degree of fact-checking against the real world. For Design Communications, the ongoing balancing of freedom and function is essential; it forms a democratic environment that prevents the domination of one strain of thinking. Across mediums and expertise, alternative directions, frameworks, and outcomes are considered. This does not mean, however, that endless, multiverse theories proliferate. ‘It’s about representing the life of the building, about understanding what kind of soul it might have,’ Aurelio reflects.

Drawing and Narrative

How else can the soul of a building find representation? Perhaps in terms of the life lived with and through it. One surprising form of architectural drawing that Design Communications offers is moving art – a medium which stretches once again what a ‘drawing’ might signify. Matthew is a member of the team who works in this way:

Drawing has always been a tool for representation, so as our technological, academic, and artistic sense of representation widens, so does the definition of drawing. We are now at a stage where my particular medium is generally accepted within the industry as a form of architectural drawing.

Still images can offer a supreme amount of detail and the opportunity to articulate a single space. Moving art's approach is different. ‘Spaces transform over time,’ Matthew reminds, ‘and moving art is a way to represent that.’ The sequencing and zooming 'in' and 'out' of spaces find ways to navigate a design story, with the focus being more on effect and user experience. ‘There’s also an auditory component that can be introduced,’ Matthew adds. ‘An analogue sketch can’t do that.’

'City of the Future' as conceived by Design Communications, led by Narinder Sagoo. © Foster + Partners

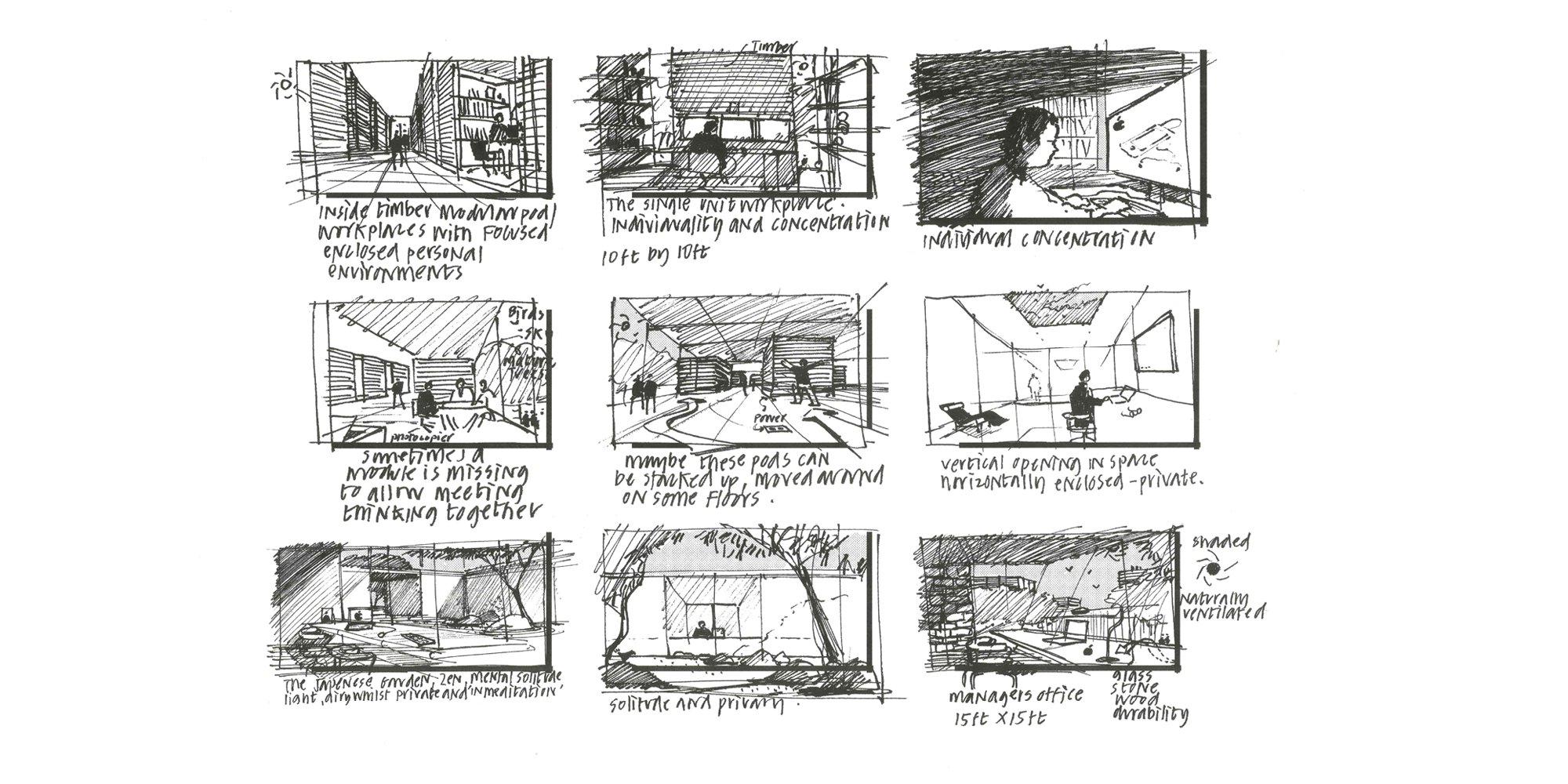

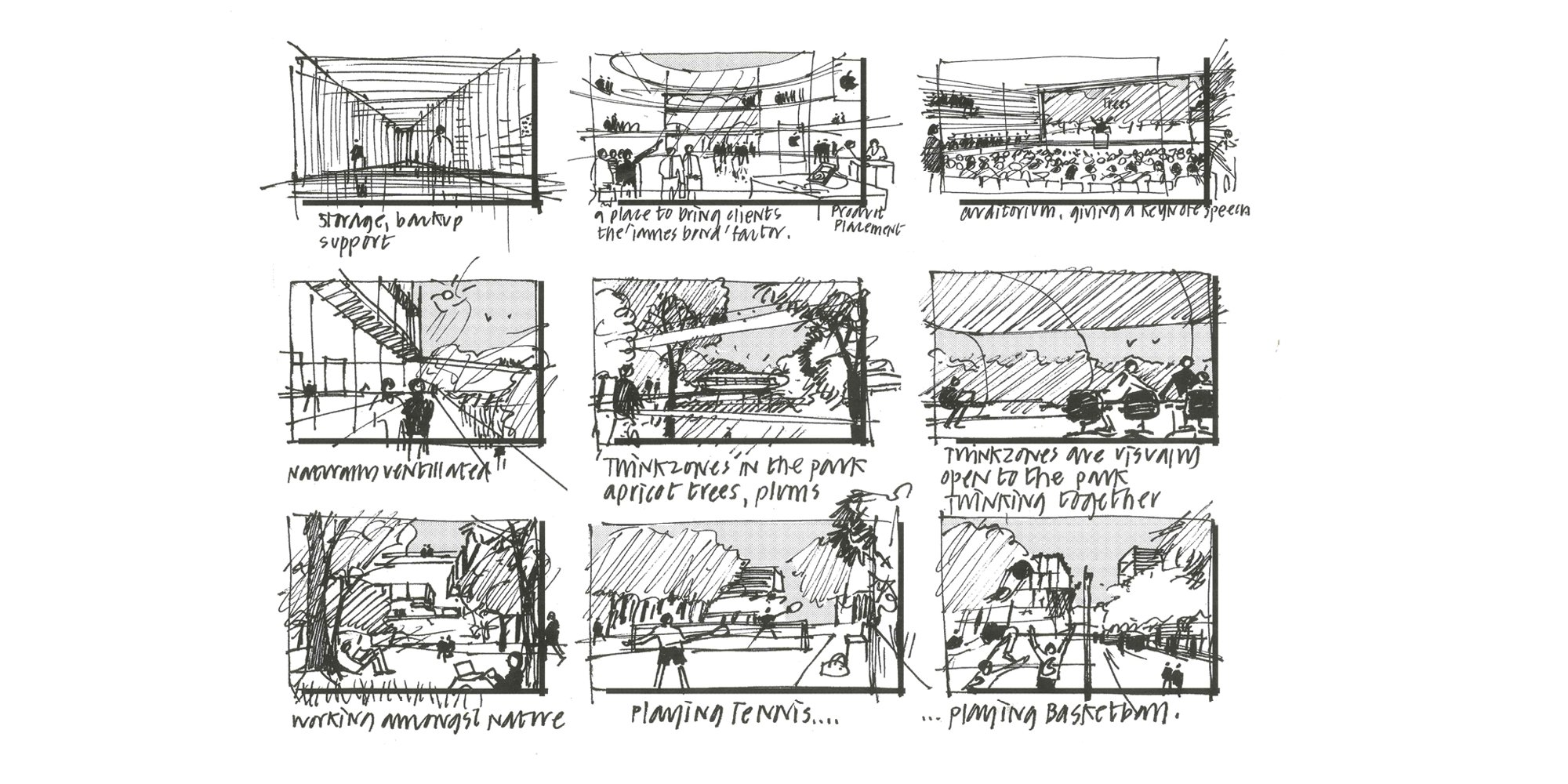

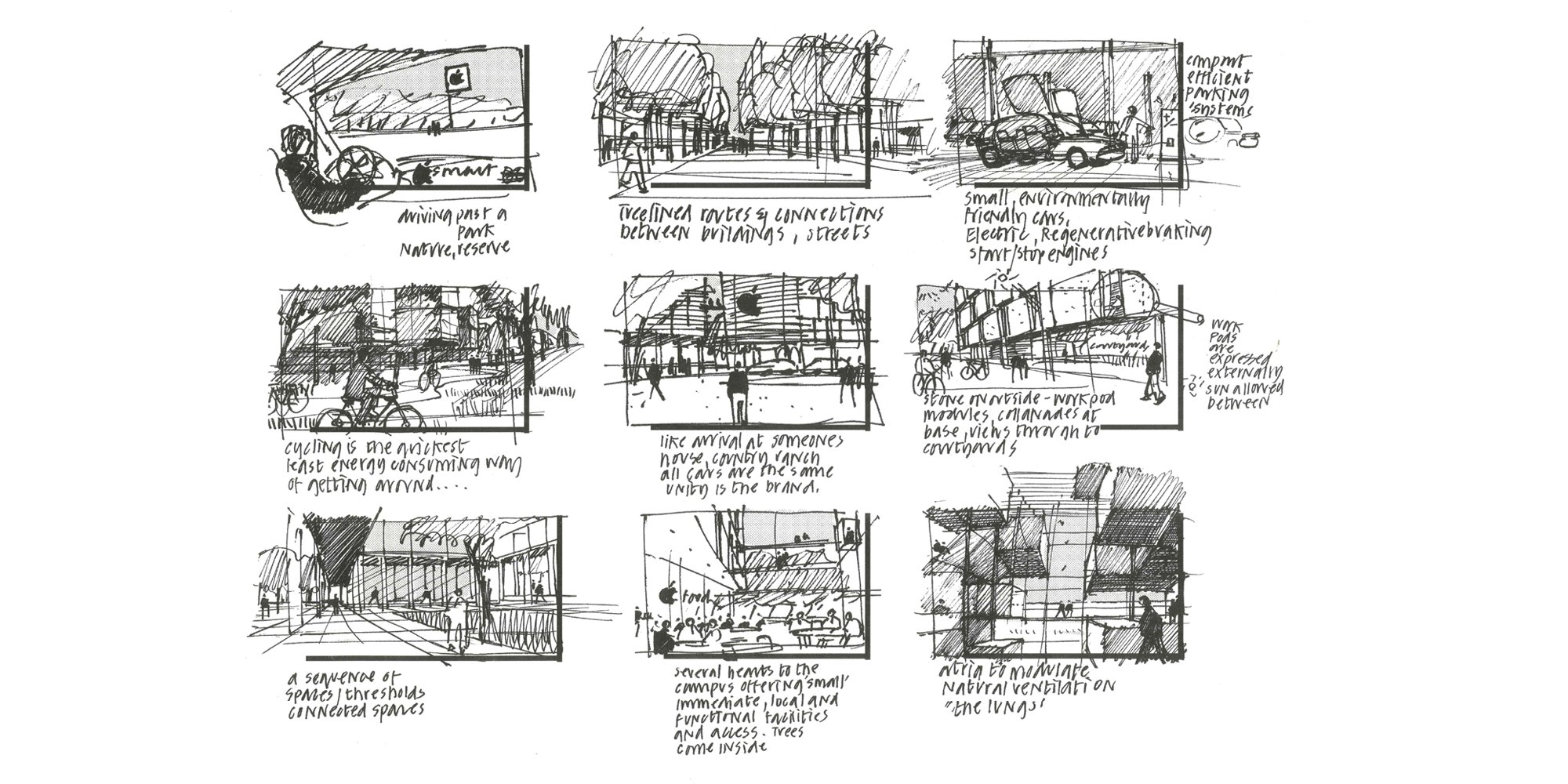

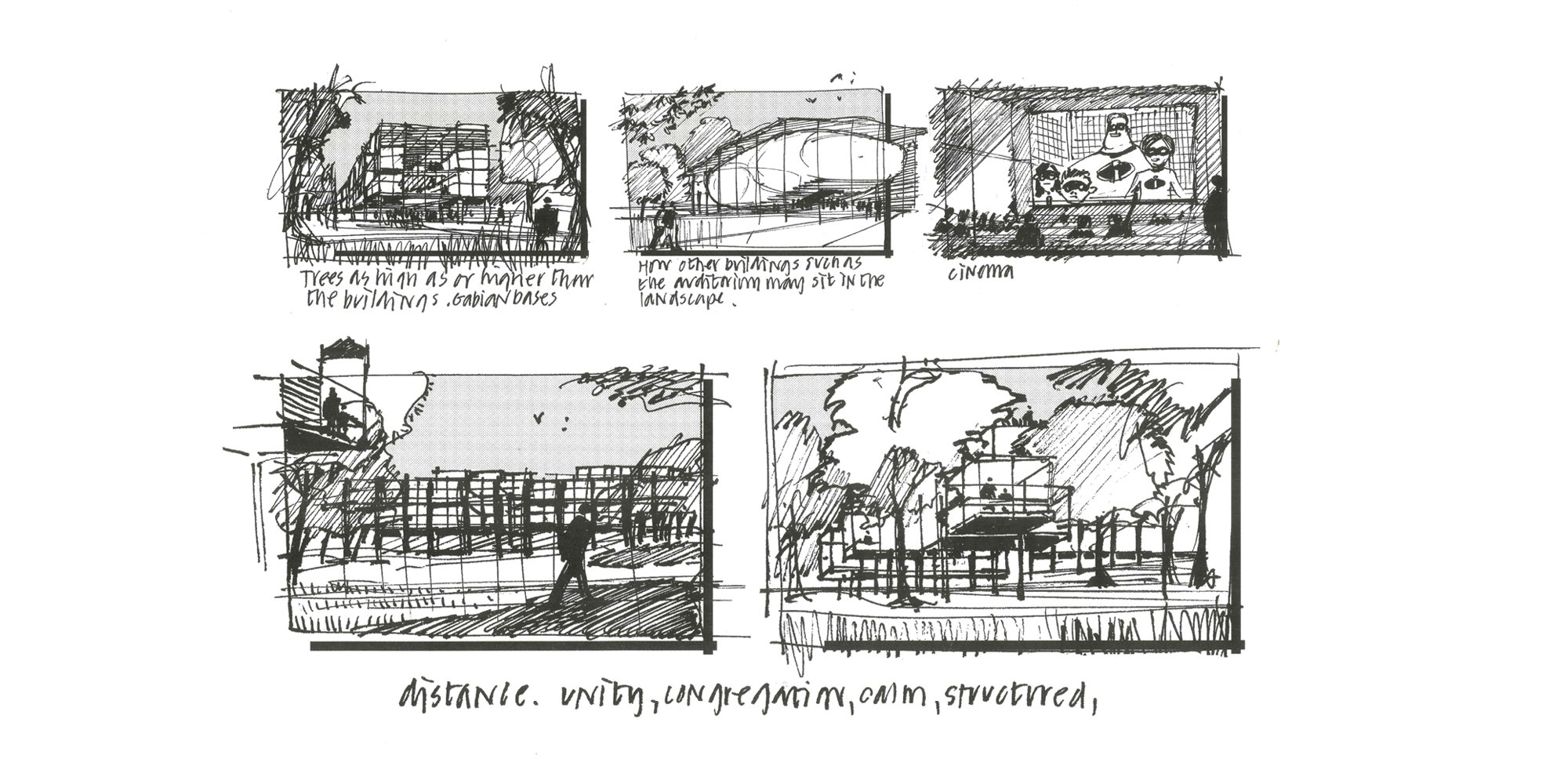

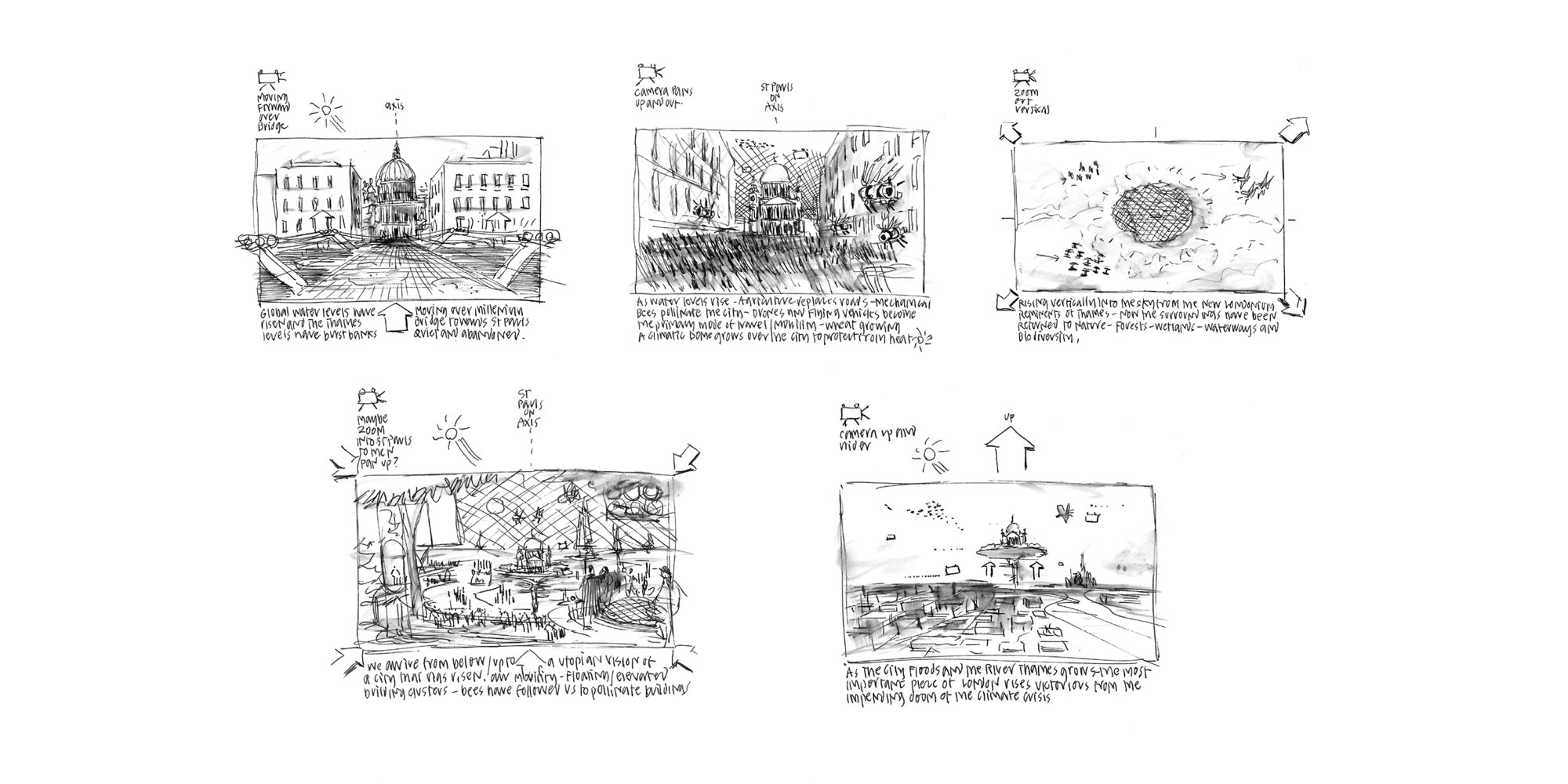

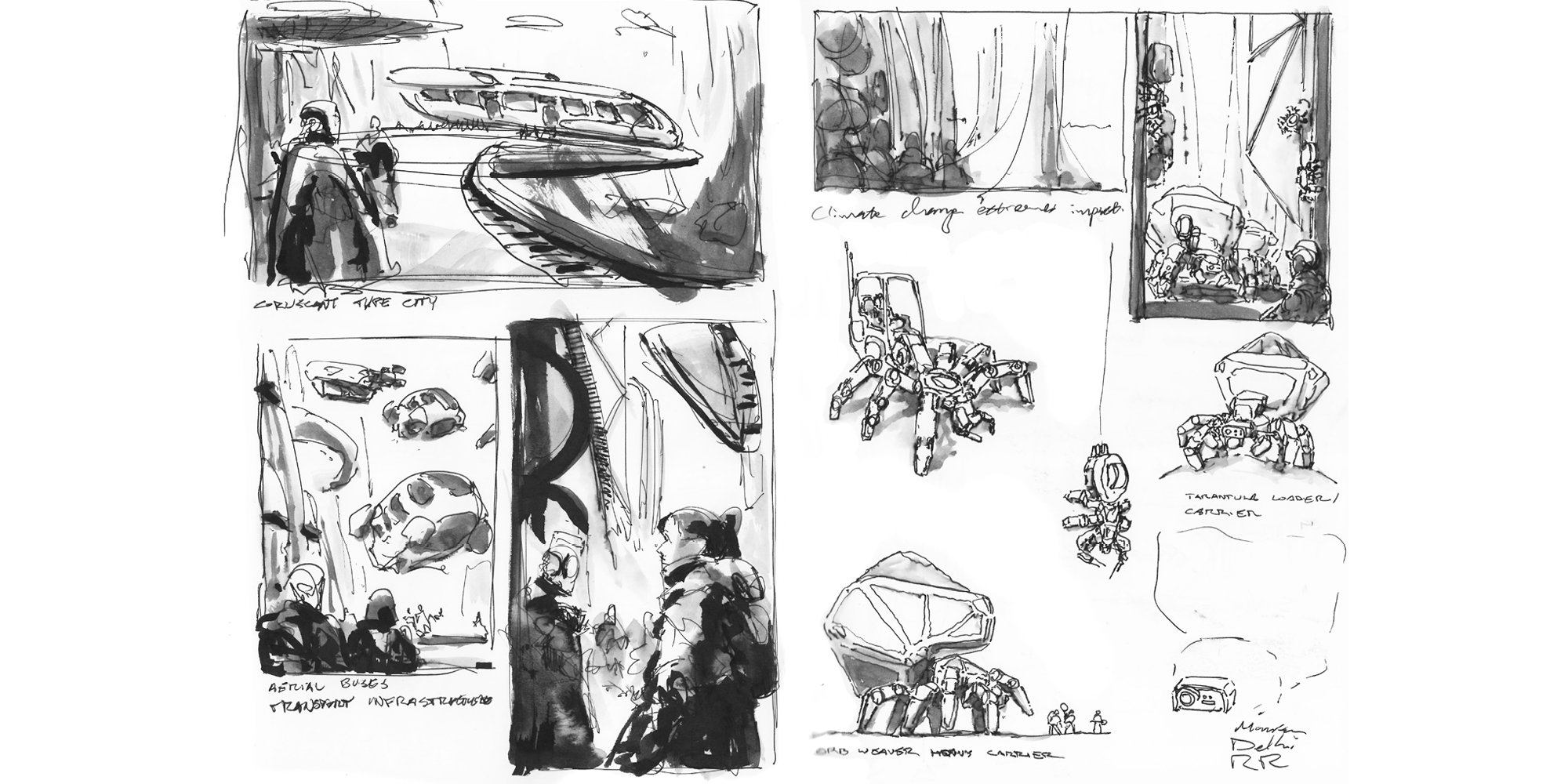

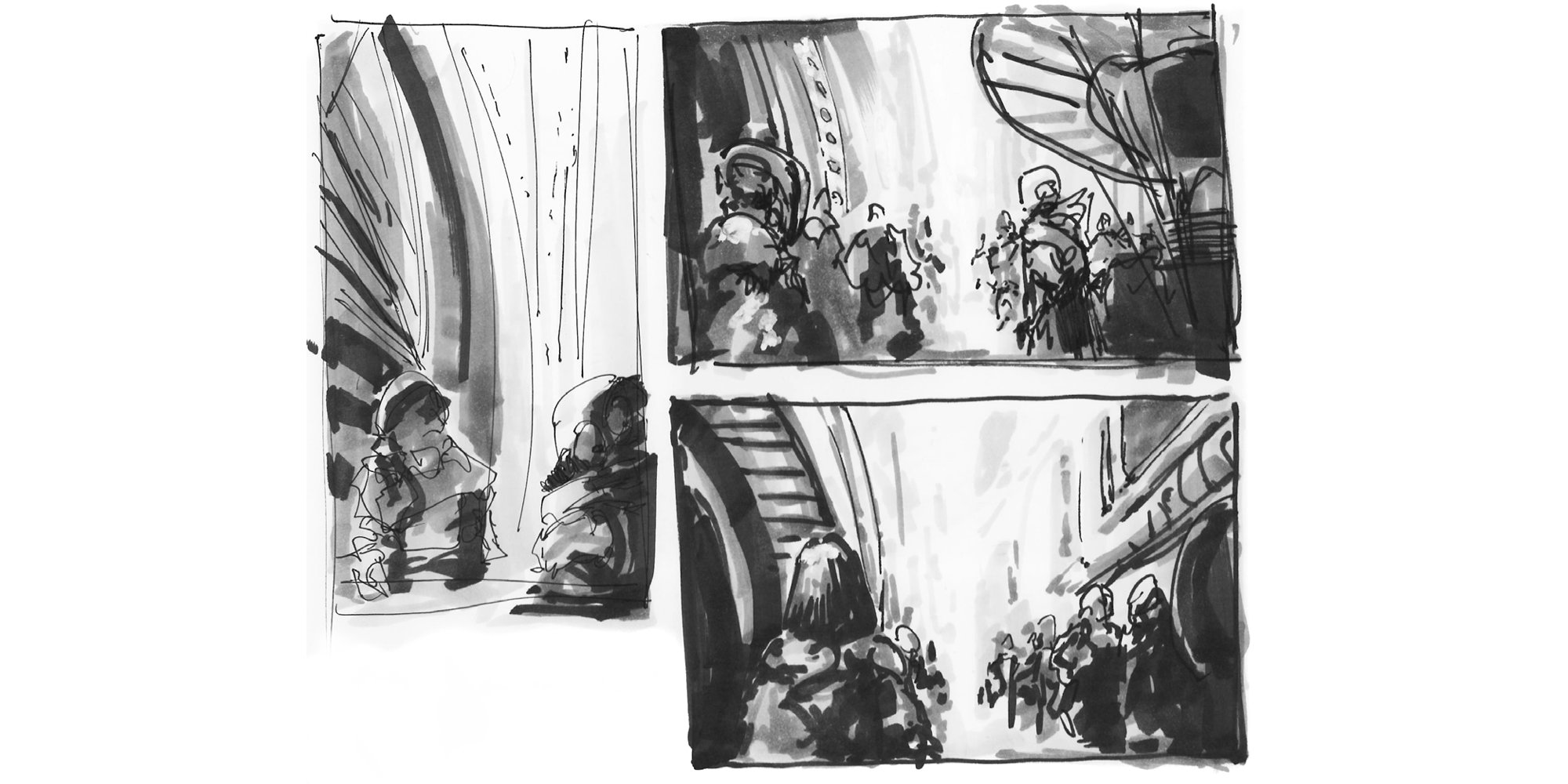

As definitions of drawing broaden in this way, the Design Communications team have absorbed and integrated practices from other domains. Often used to clarify how a theme might develop, a storyboard might more readily associated with the graphic novel, the comic strip, the film – and less so with architecture. However, the entire team use storyboards to think about how buildings and urban plans will be used, how sequences of spaces connect with one another, and how a project might develop over time.

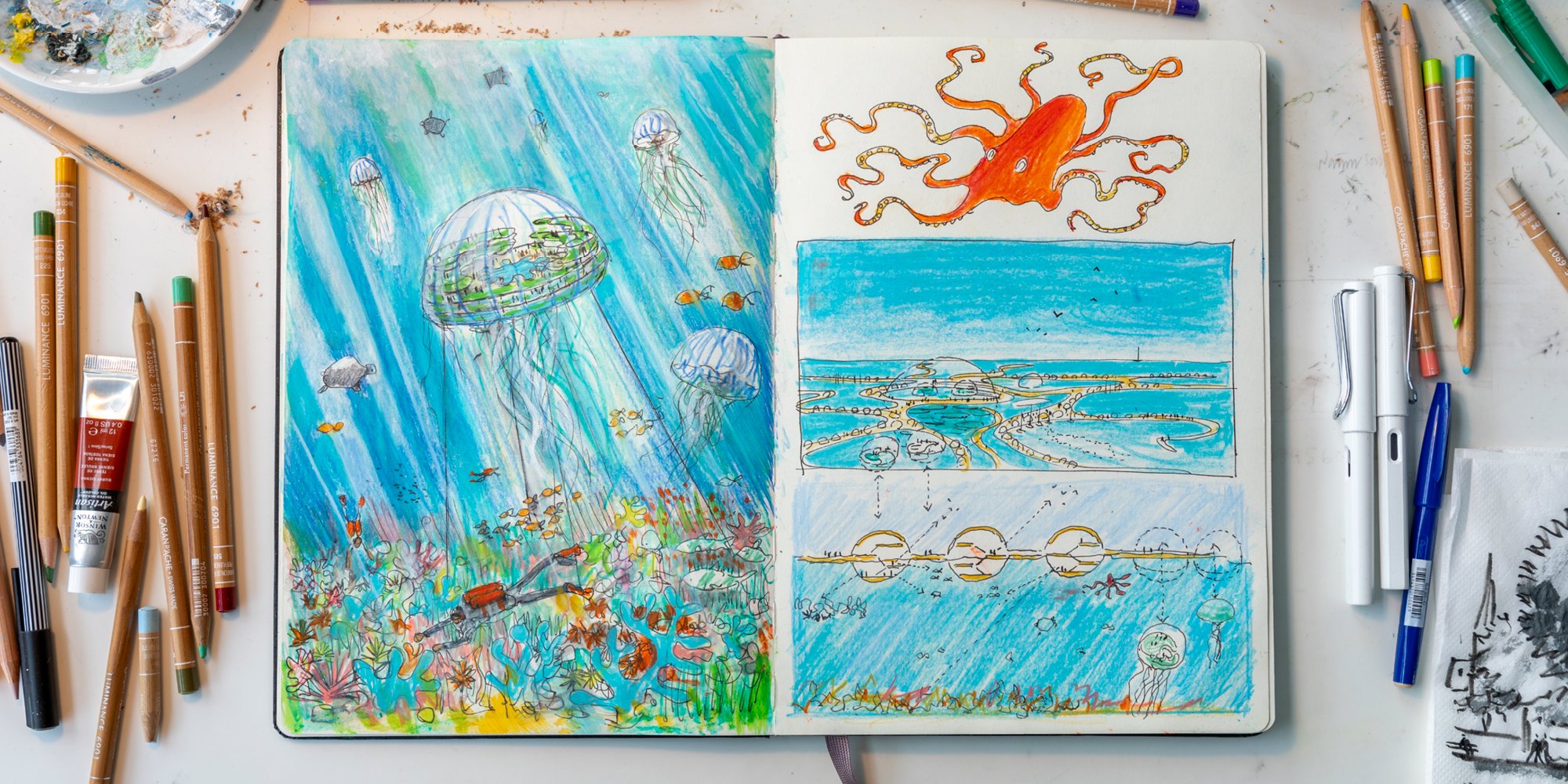

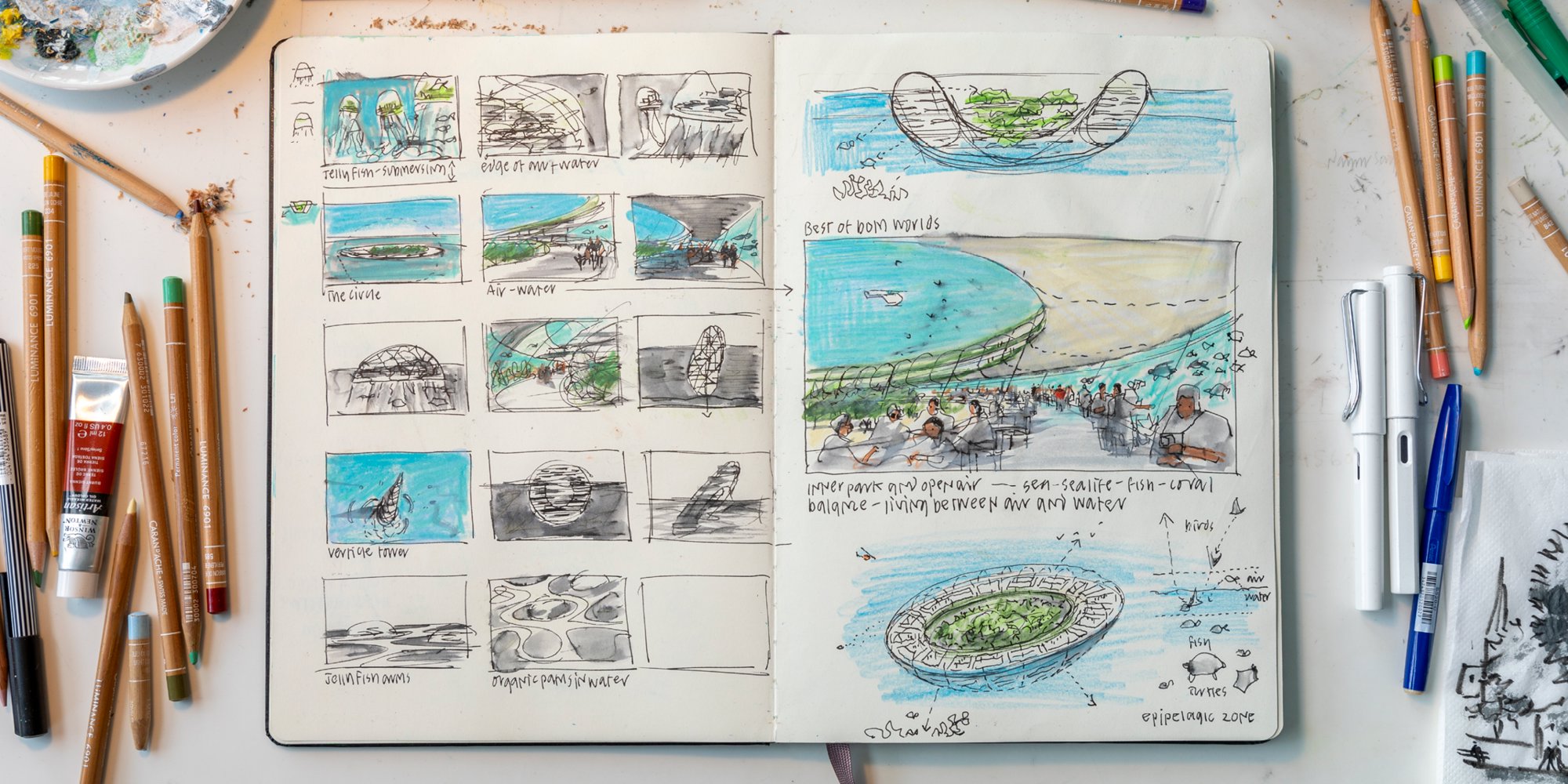

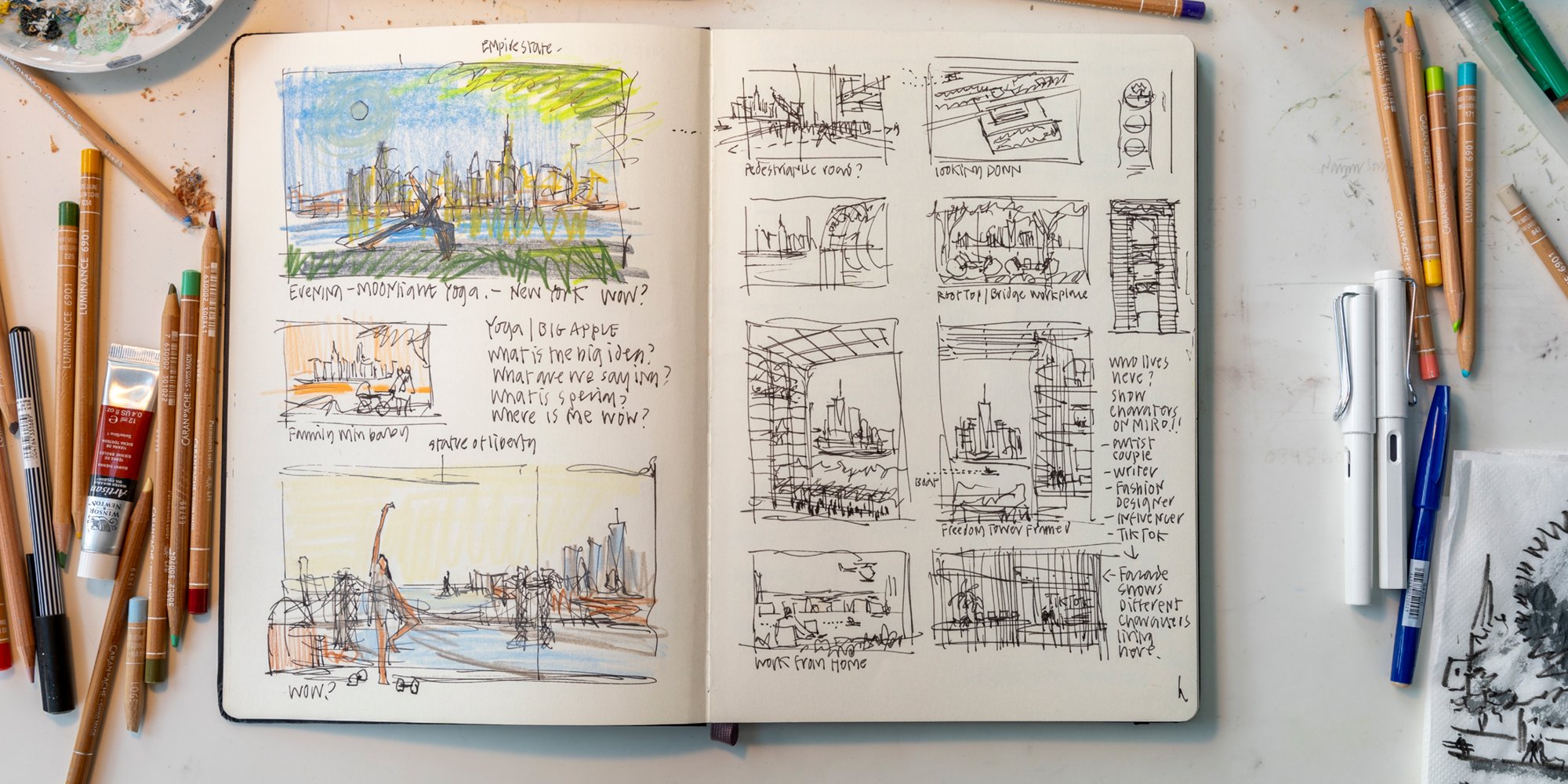

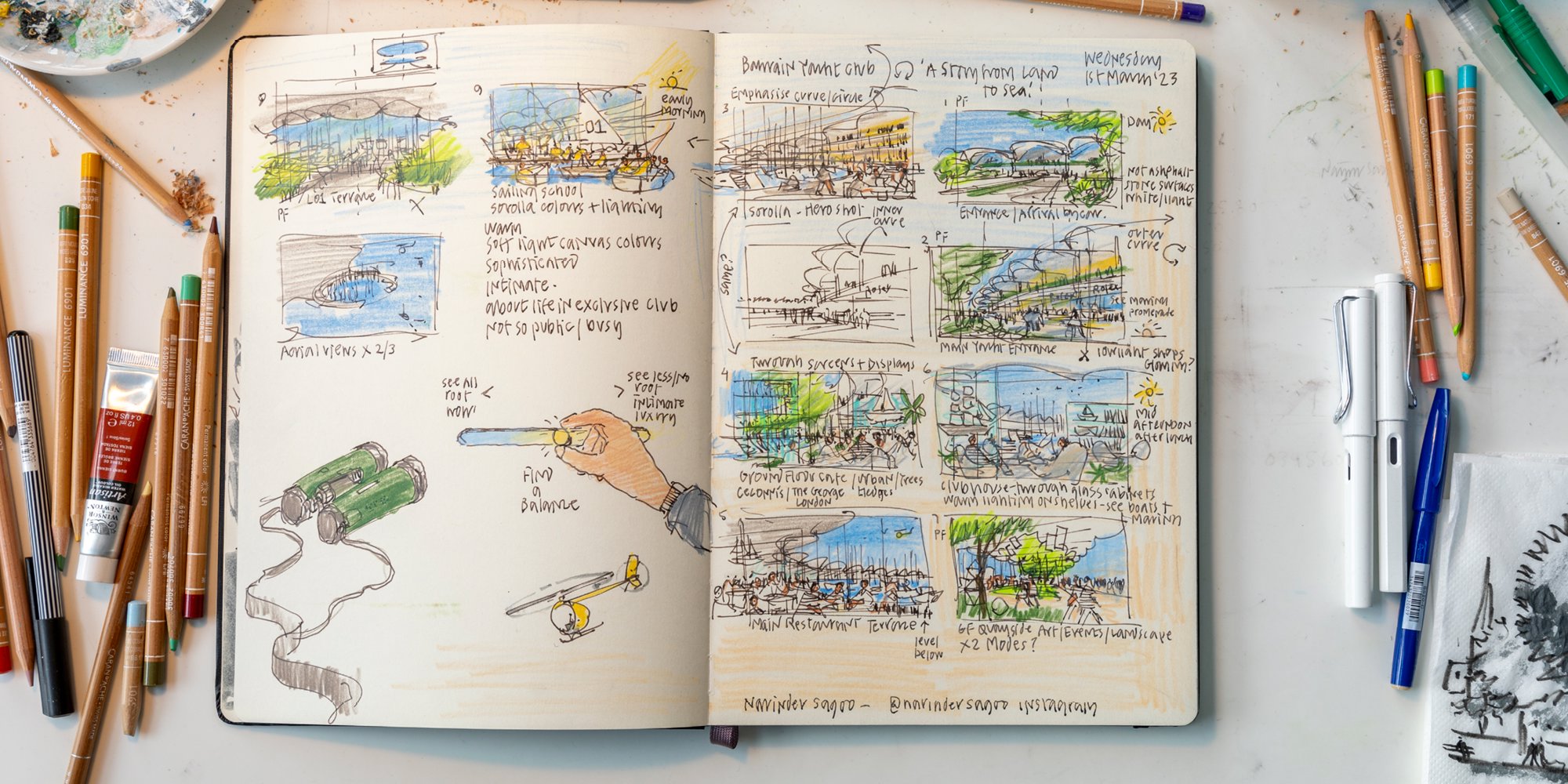

Storyboards are a way for the Design Communications team to navigate the spatial, visual, and narratological aspects of a design. © Foster + Partners

Storyboards are a way for the Design Communications team to navigate the spatial, visual, and narratological aspects of a design. © Foster + Partners

Storyboards are a way for the Design Communications team to navigate the spatial, visual, and narratological aspects of a design. © Foster + Partners

Storyboards are a way for the Design Communications team to navigate the spatial, visual, and narratological aspects of a design. © Foster + Partners

Storyboards are a way for the Design Communications team to navigate the spatial, visual, and narratological aspects of a design. © Foster + Partners

Storyboards are a way for the Design Communications team to navigate the spatial, visual, and narratological aspects of a design. © Foster + Partners

Grounded in Reality

In today’s world of architectural representation, there is a fine line between creative absorption and creating images for images’ sake. Most recently, the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) has pressurised this boundary. AI has already transformed much of the image-making world due to the unprecedented speed and increasing accuracy with which it can process and reconfigure billions of images. For those in the visual arts, the concerns are manifold. The training of an algorithm on images without permission from their owners or subjects has raised questions of artistic property; similarly, creating images that distort a reality (as AI has been leveraged to), has raised questions about influence, citation, and truth. These questions have always been present in art – though arguably never to this scale or potency. Even the definition of ‘art’ itself has come under new scrutiny, with the Oxford English Dictionary recently adding to their entry the qualification ‘human-made’.

The discourse surrounding AI often dwells on its unregulated, obfuscating use. However, the technology does offer practical and responsible applications for Design Communications. AI can quickly generate details for three-dimensional photoreal artworks and offer a variety of composition options that the team can then compare. Rather than replacing the artist, the team consider AI to be another medium of drawing. ‘It is never an end-point, but a tool,’ Victoria reminds. An AI image generator cannot explain why one image will work ‘better’ as a visual composition, let alone as an architectural proposition. Nor can it think from scratch, or read between the (construction) lines, of what an architect might be thinking or what a client might want. The team’s drawings are always related to the design at hand, always sensitive to the reality of the project.

The properties of the drawing medium have a great deal to do with how architecture is created and how it emerges from thought to appear in the world.

David Ross Scheer, The Death of Drawing

Many members of Design Communications are trained as architects, though some hail from other artistic fields to offer alternative outlooks and techniques. Together, the team offer a composite understanding of how images work, how these images become architectural, and the consequences of architectural images on a design. From the conceptual stills that Jordan creates to the sketches that Nicte animates, to the moving art that Matthew edits, all the team’s drafted mediums require critical understanding and discernment to work effectively.

The Appeal of the Sketch

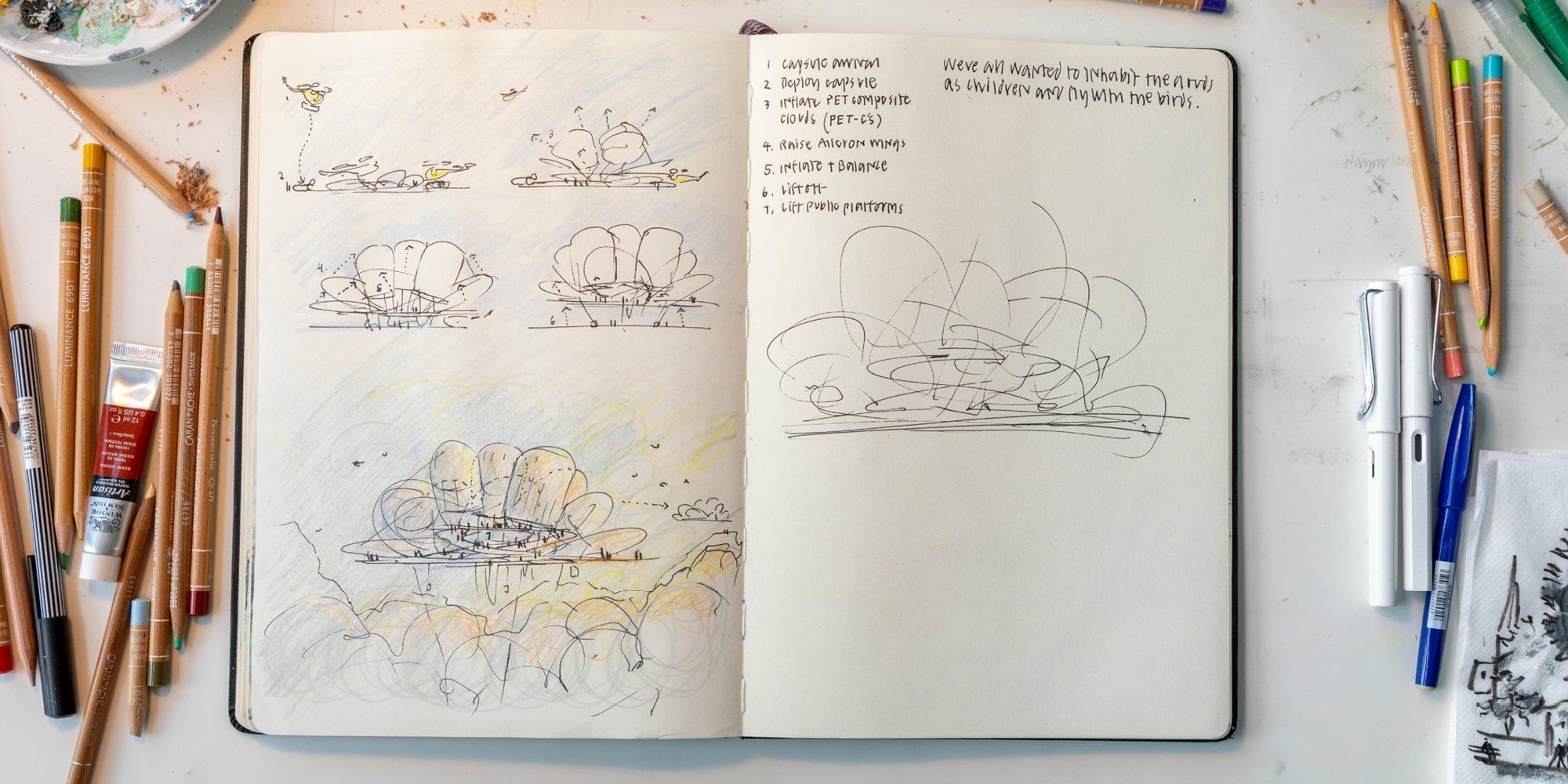

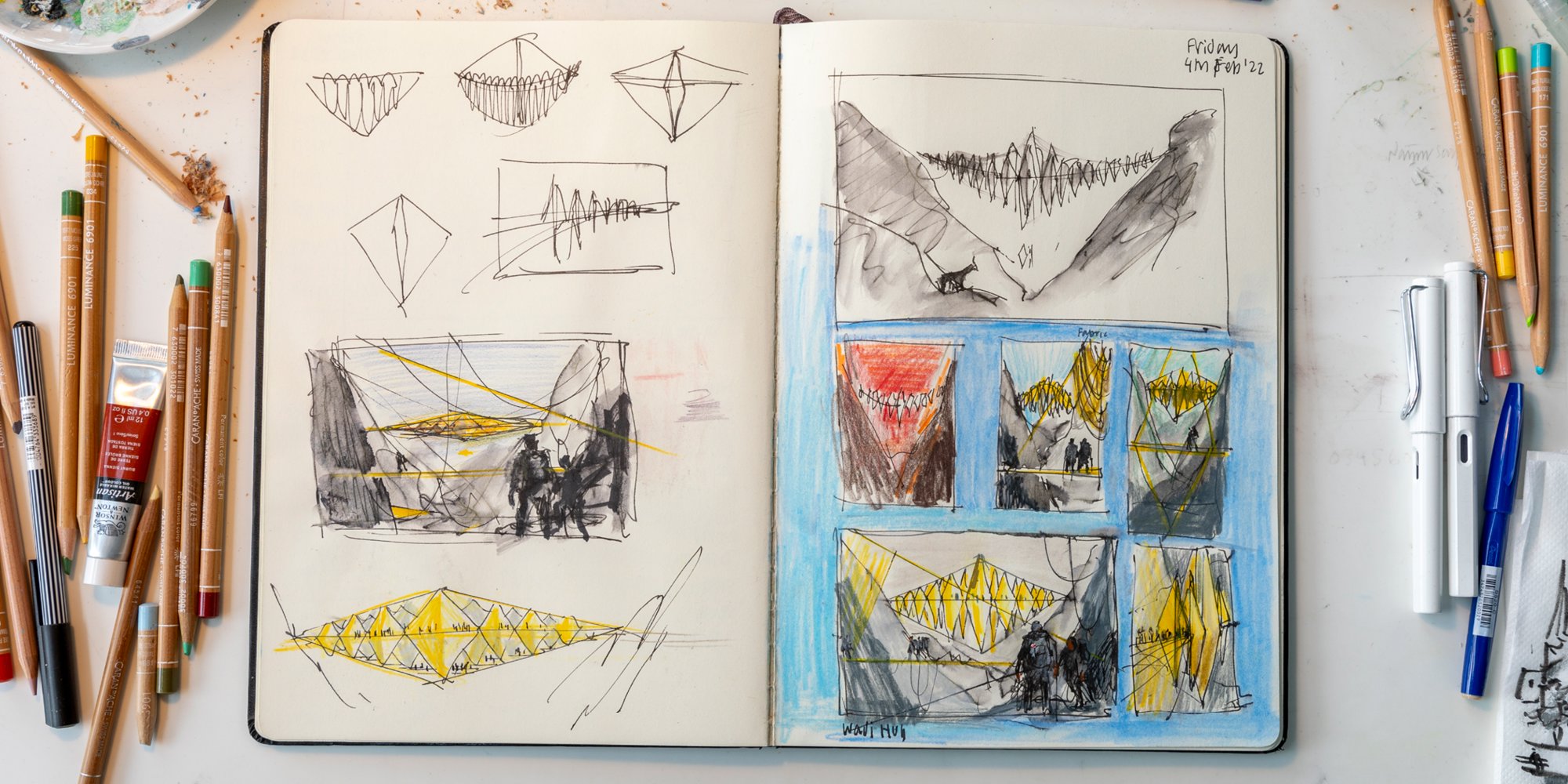

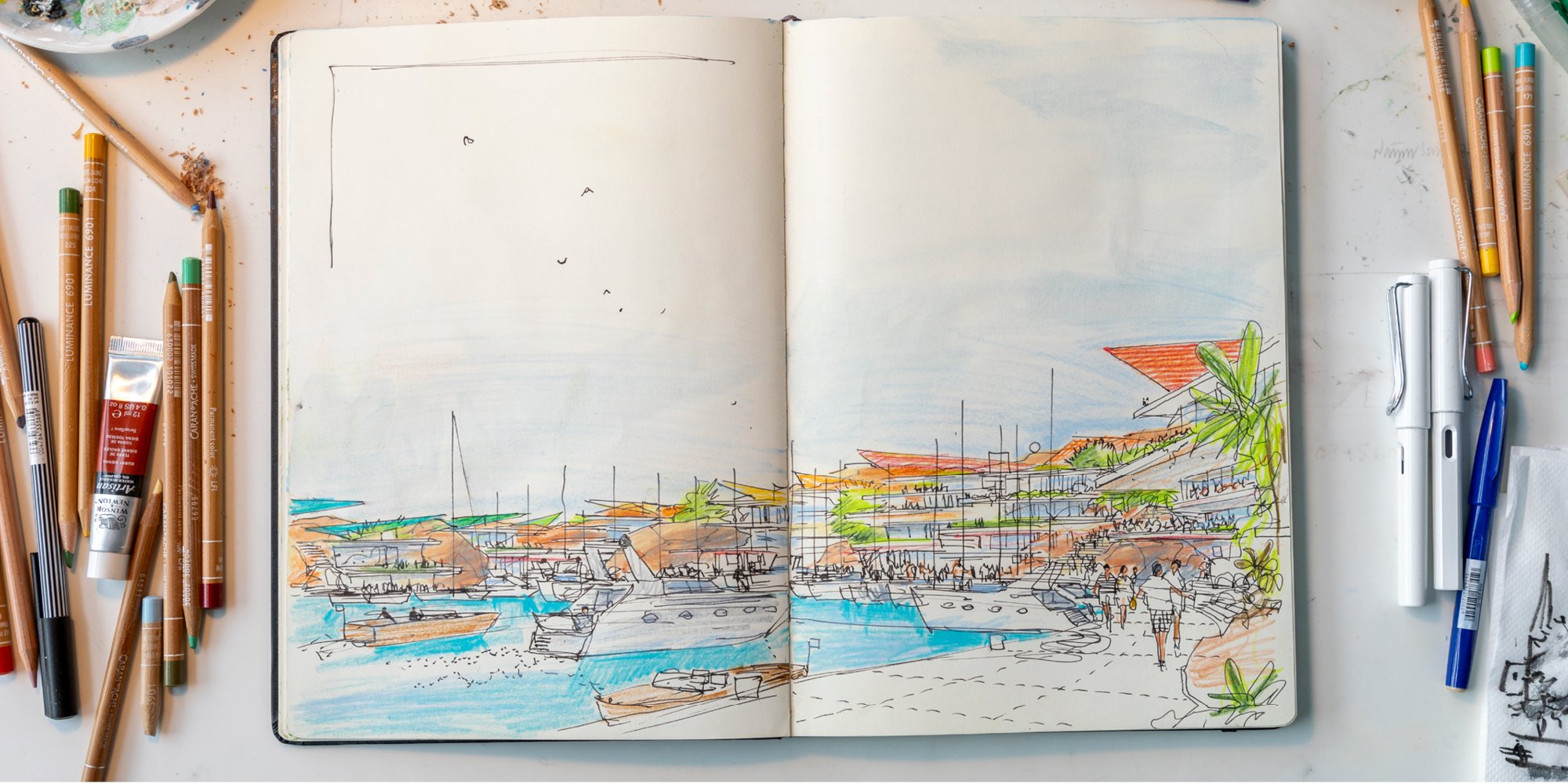

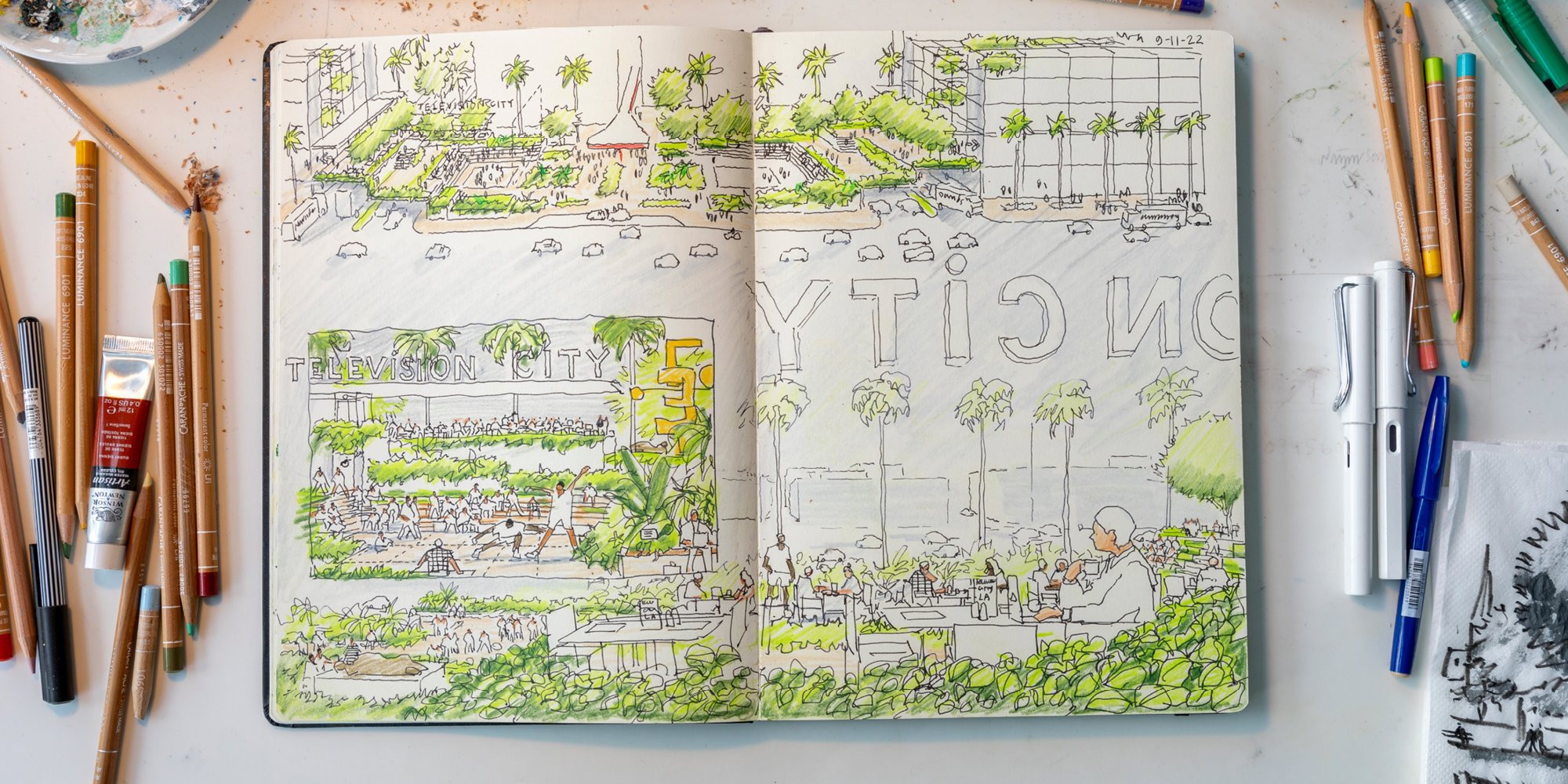

In a world of proliferation and technological acceleration, one architectural drawing practice remains indispensable: the sketch. Sketching is a reliable way to ‘figure out what we are thinking,’ as the team put it. In a studio environment where paper and a pencil are always within reach, sketching is a way to test and articulate ideas in real time. An idea moves from the mind – down through the spine, arm, wrist, hand, pencil, and finally – to the page. Sketching is a reciprocal activity between the page and the drawer that can be understood, perhaps, as a form of mediation between idea and reality. It is a key tool for any designer.

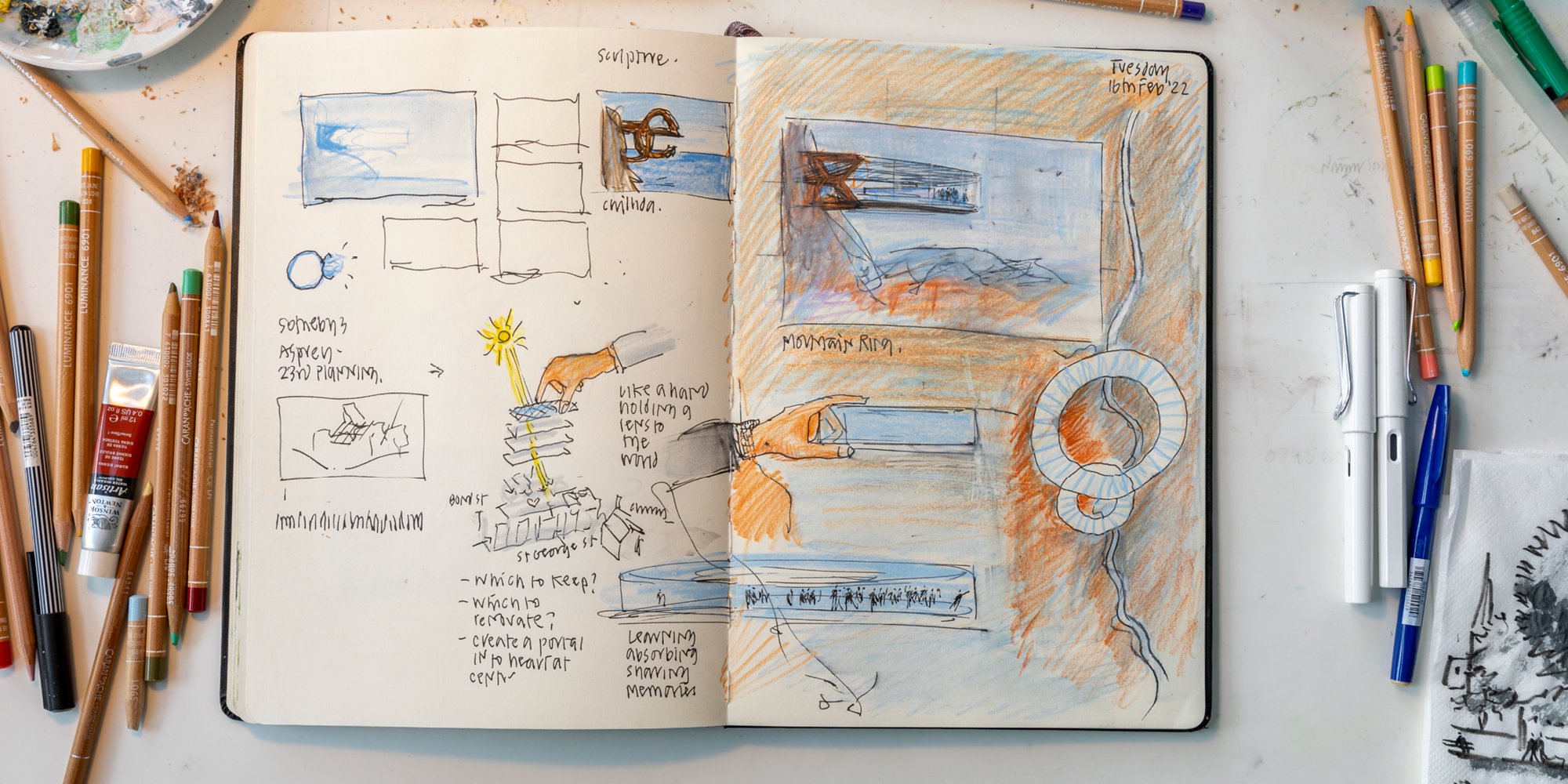

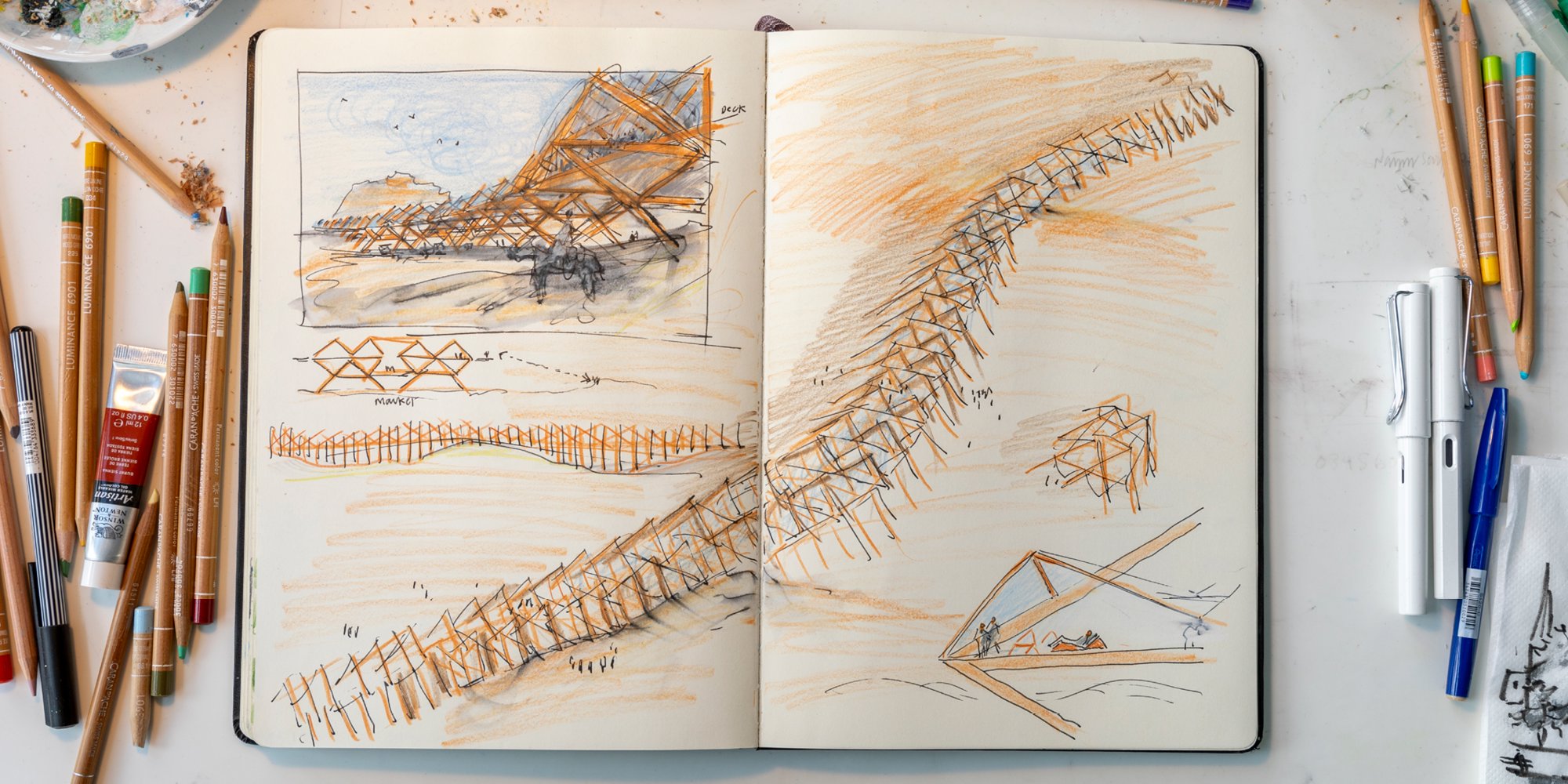

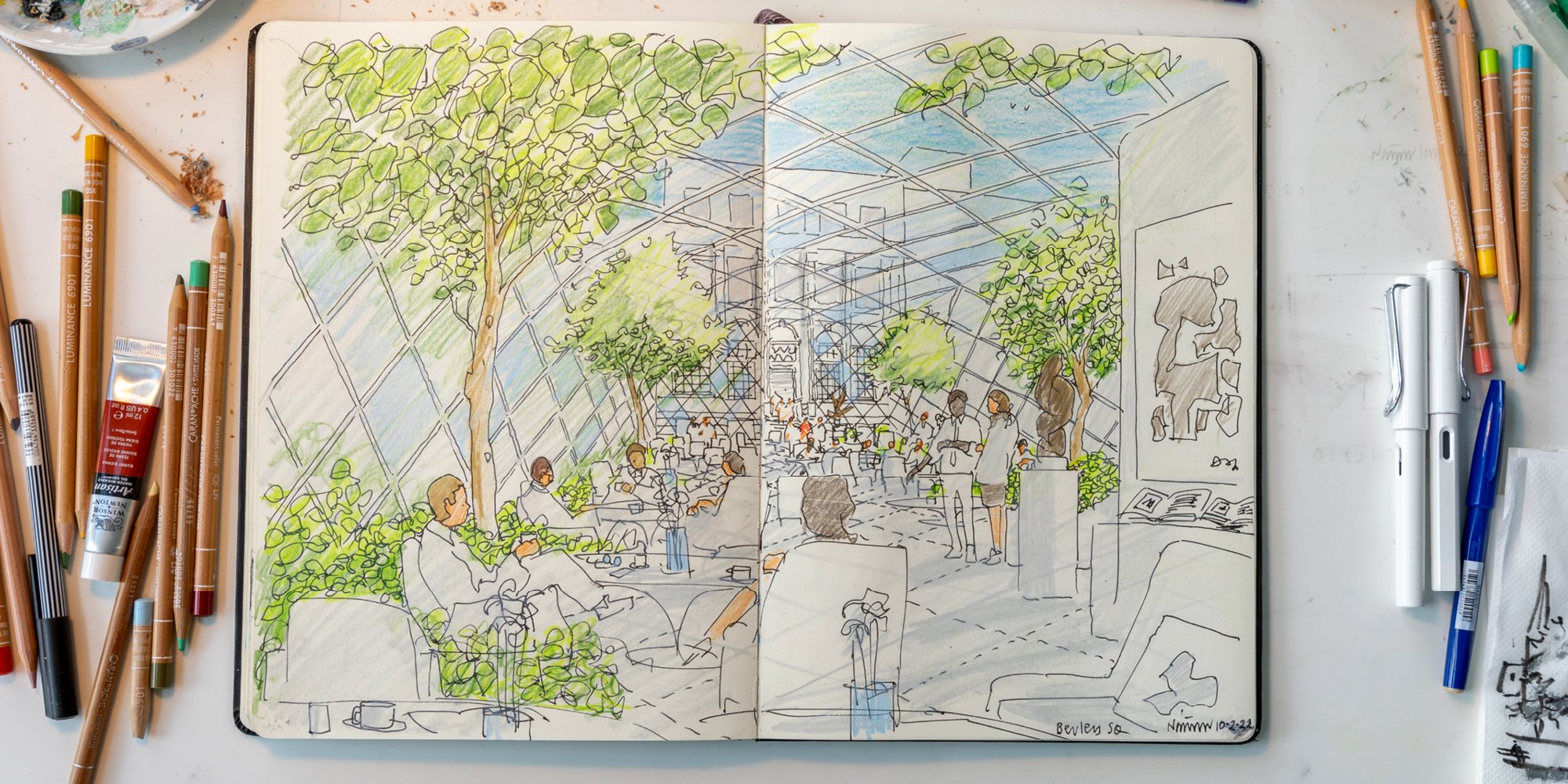

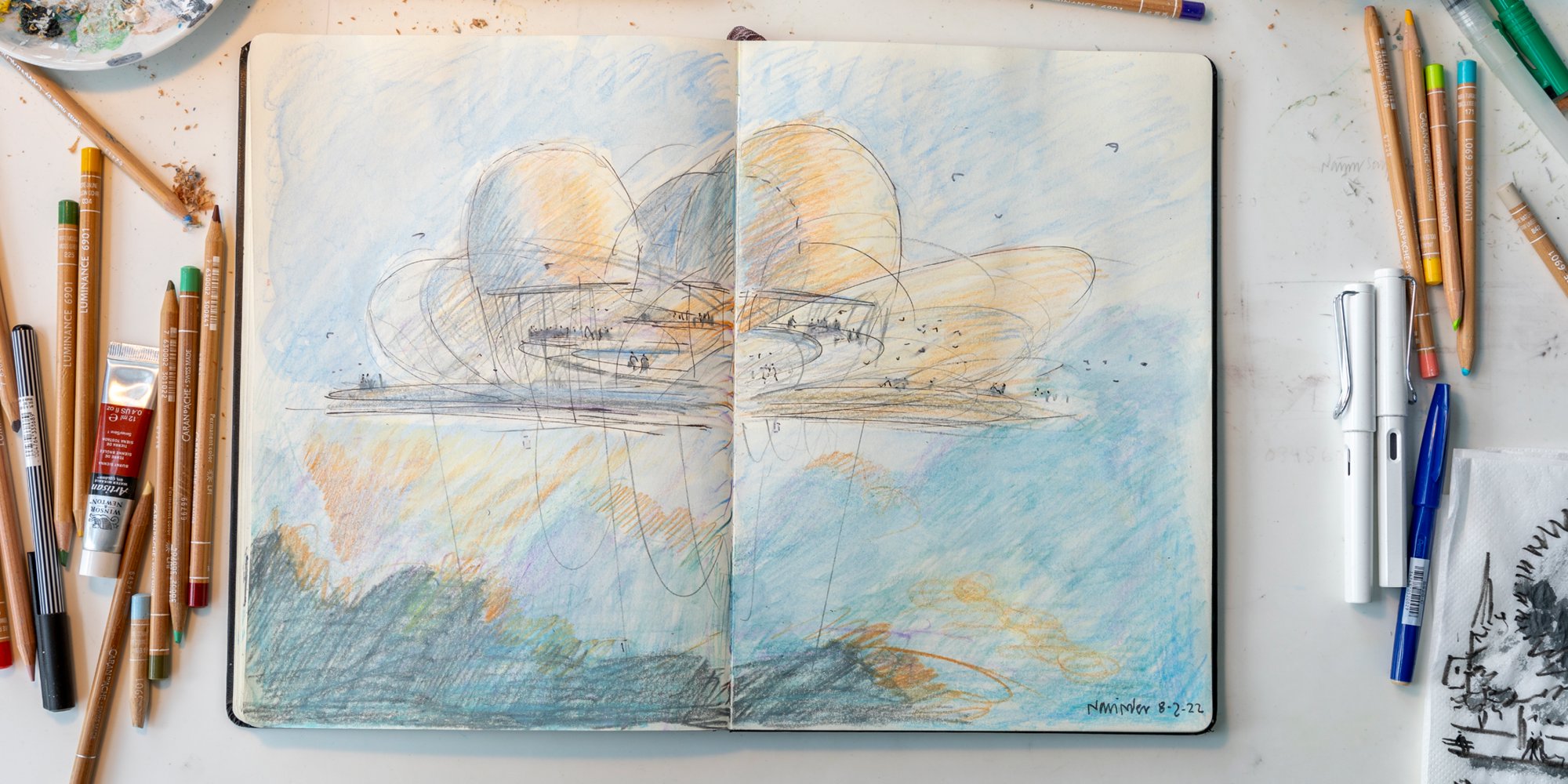

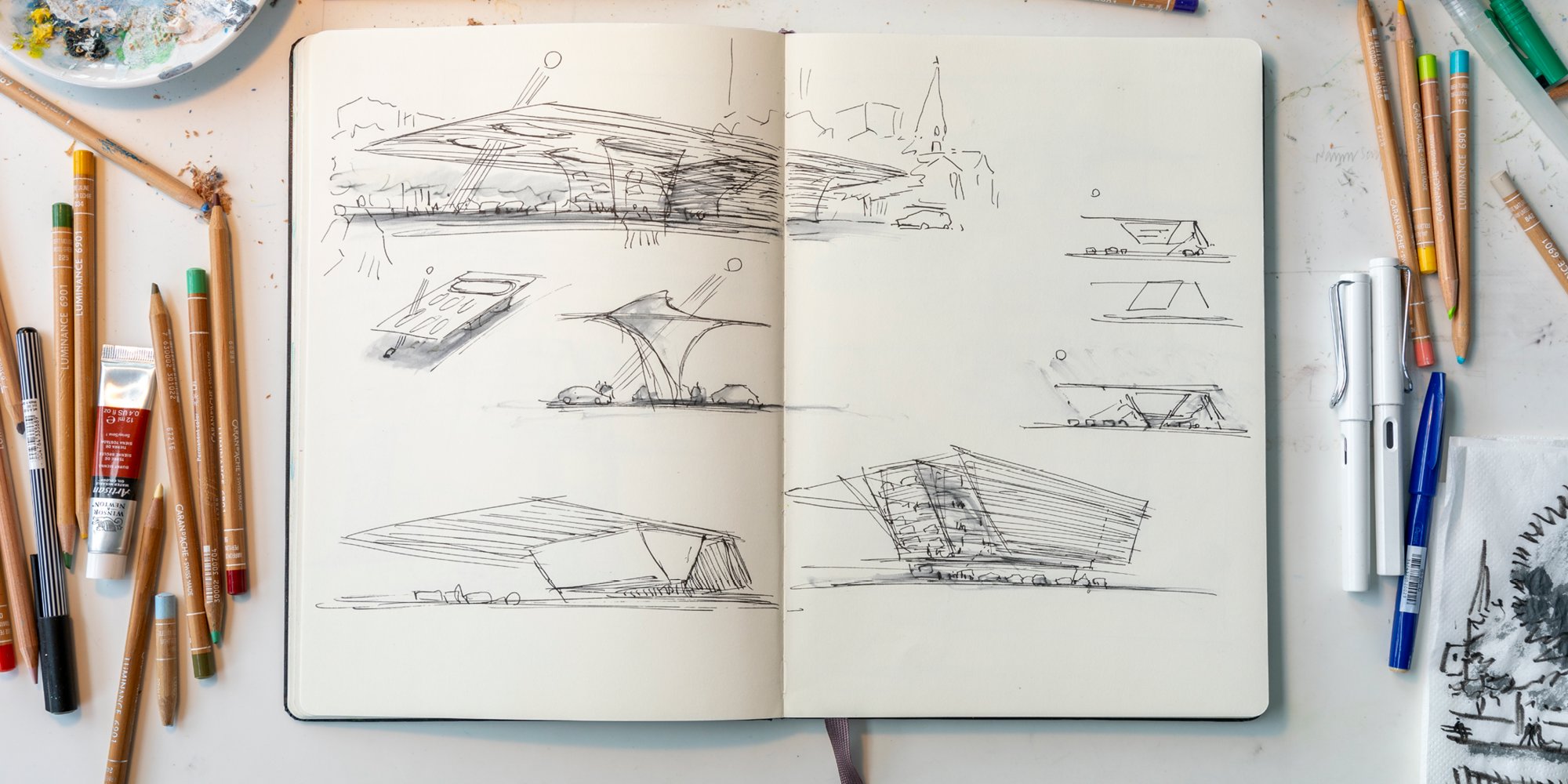

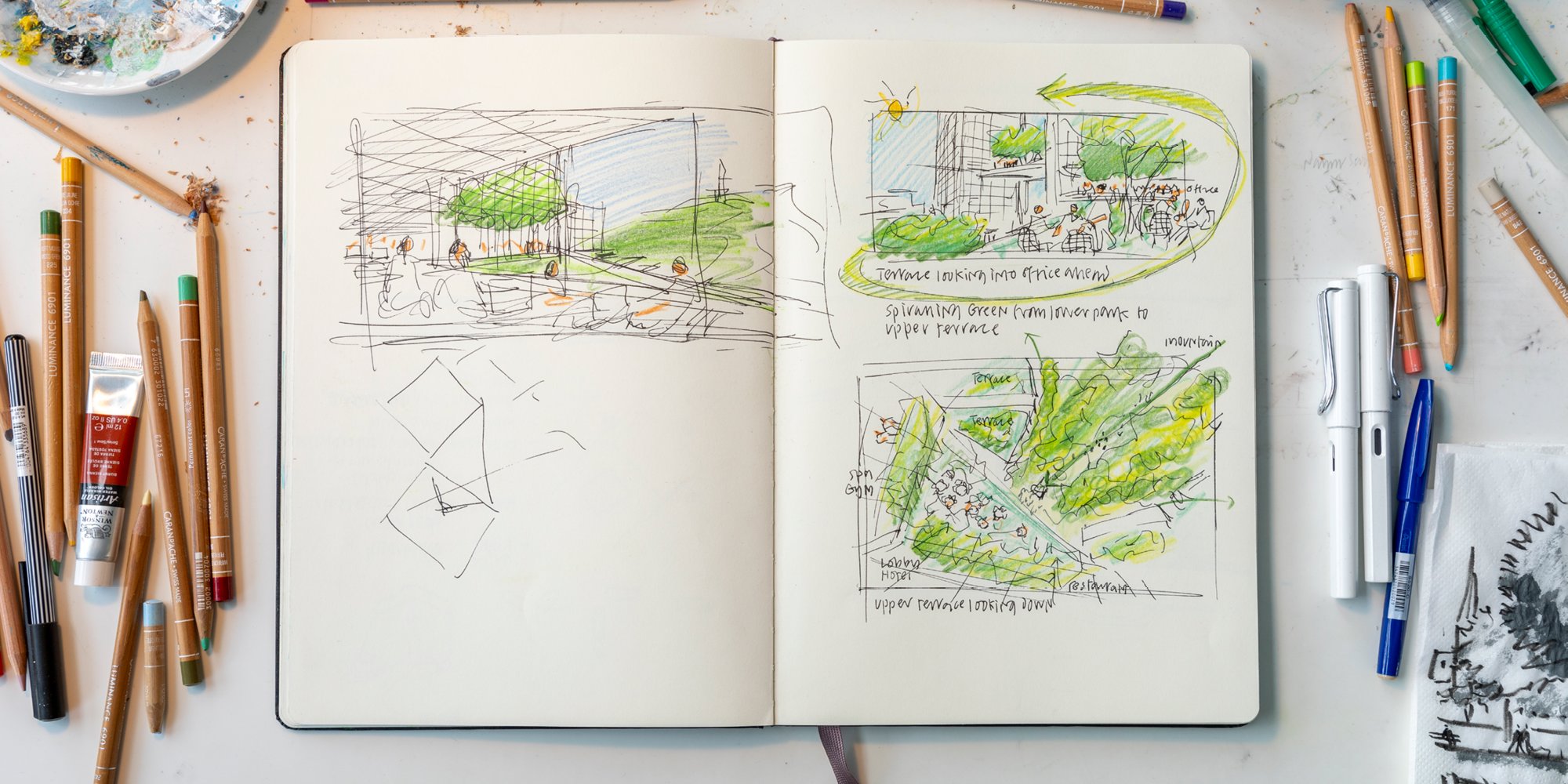

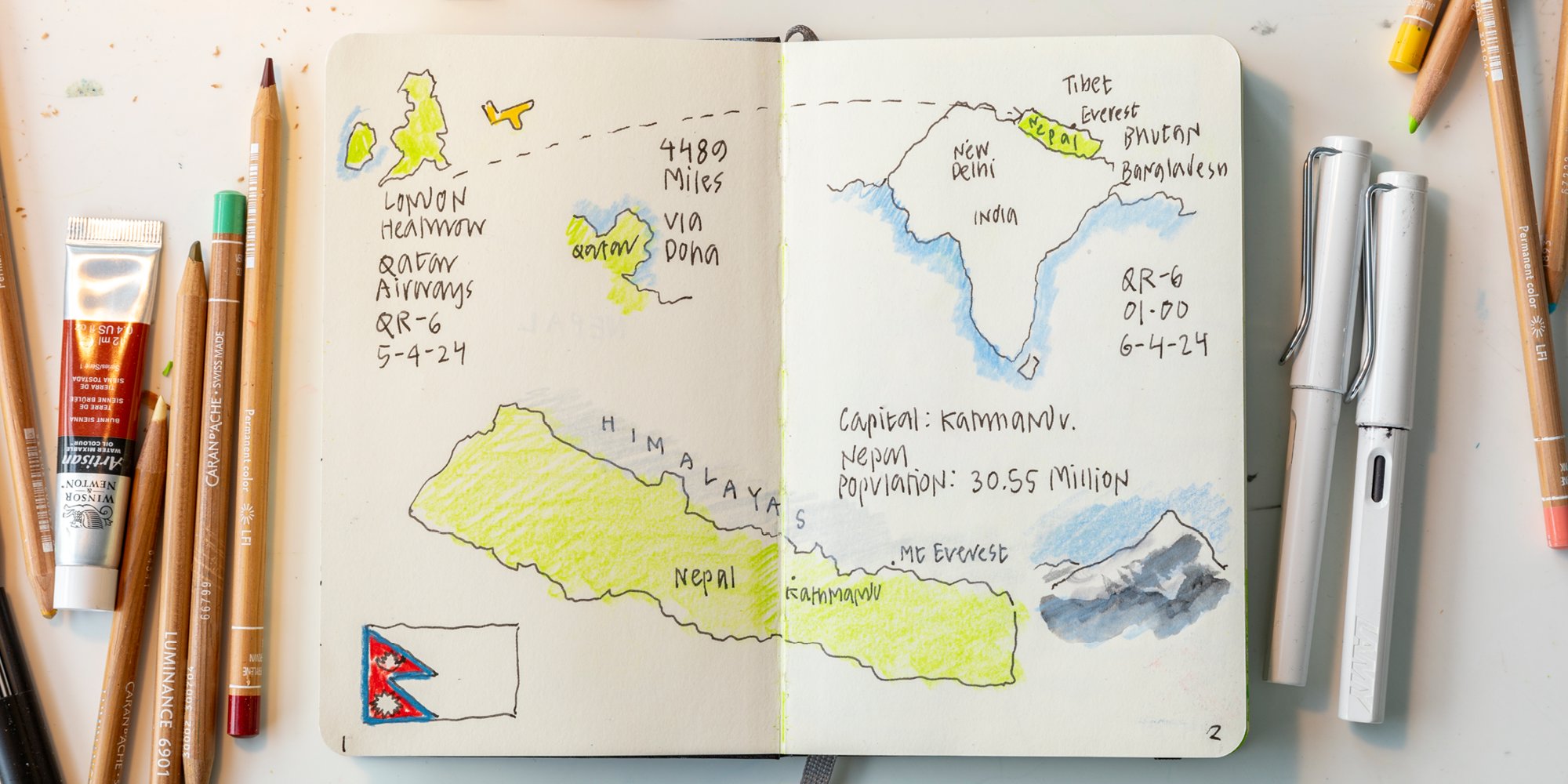

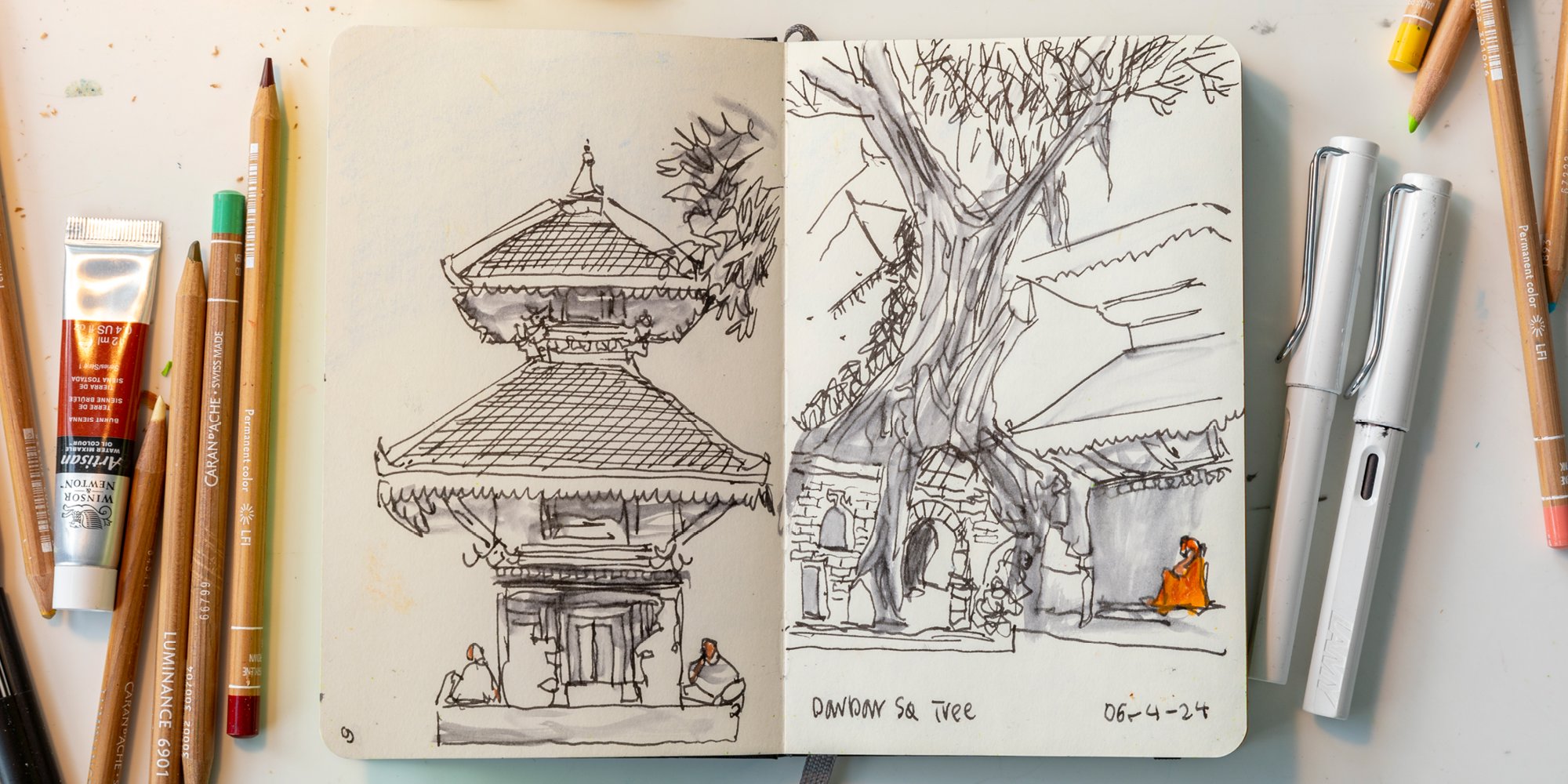

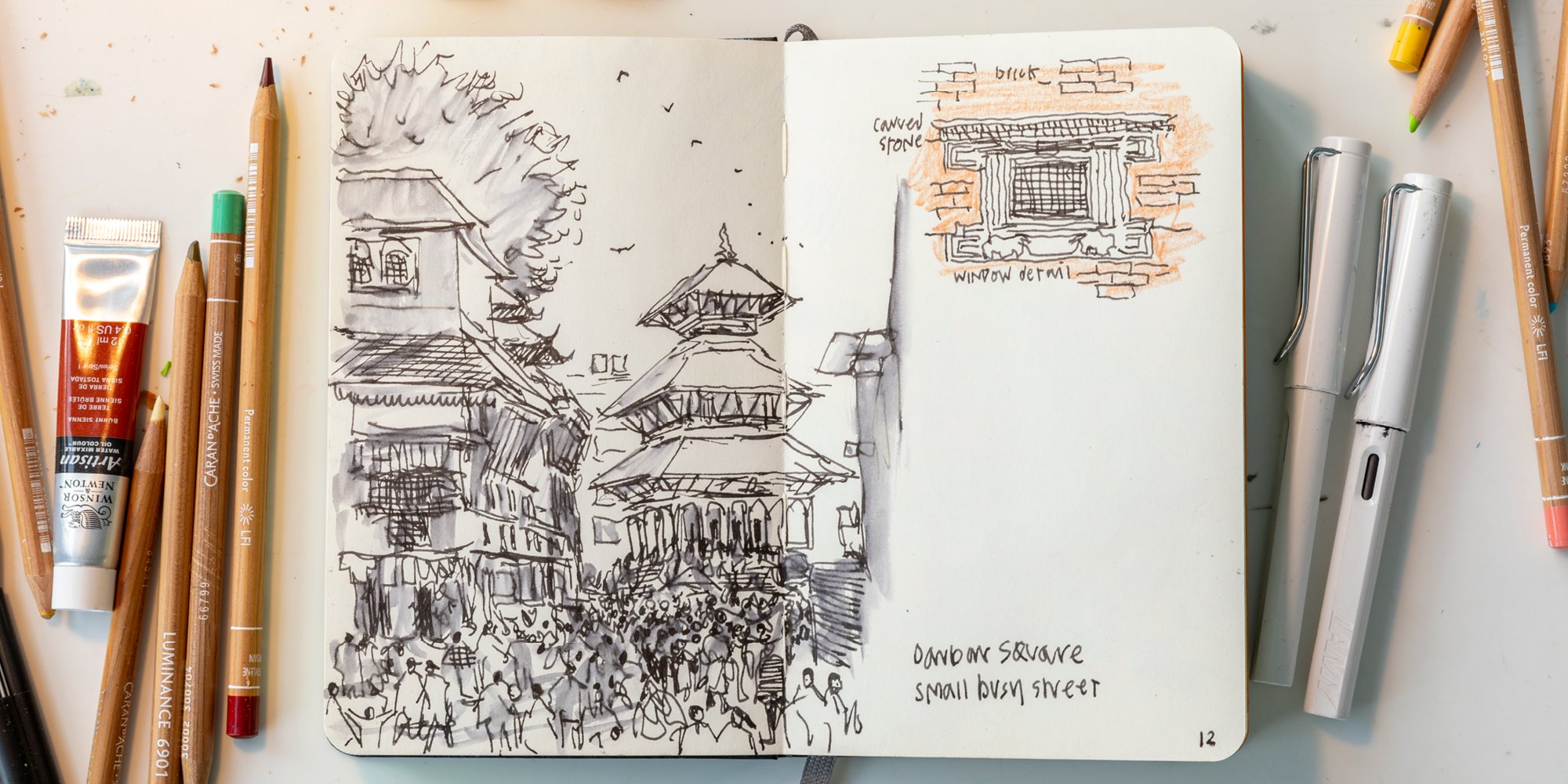

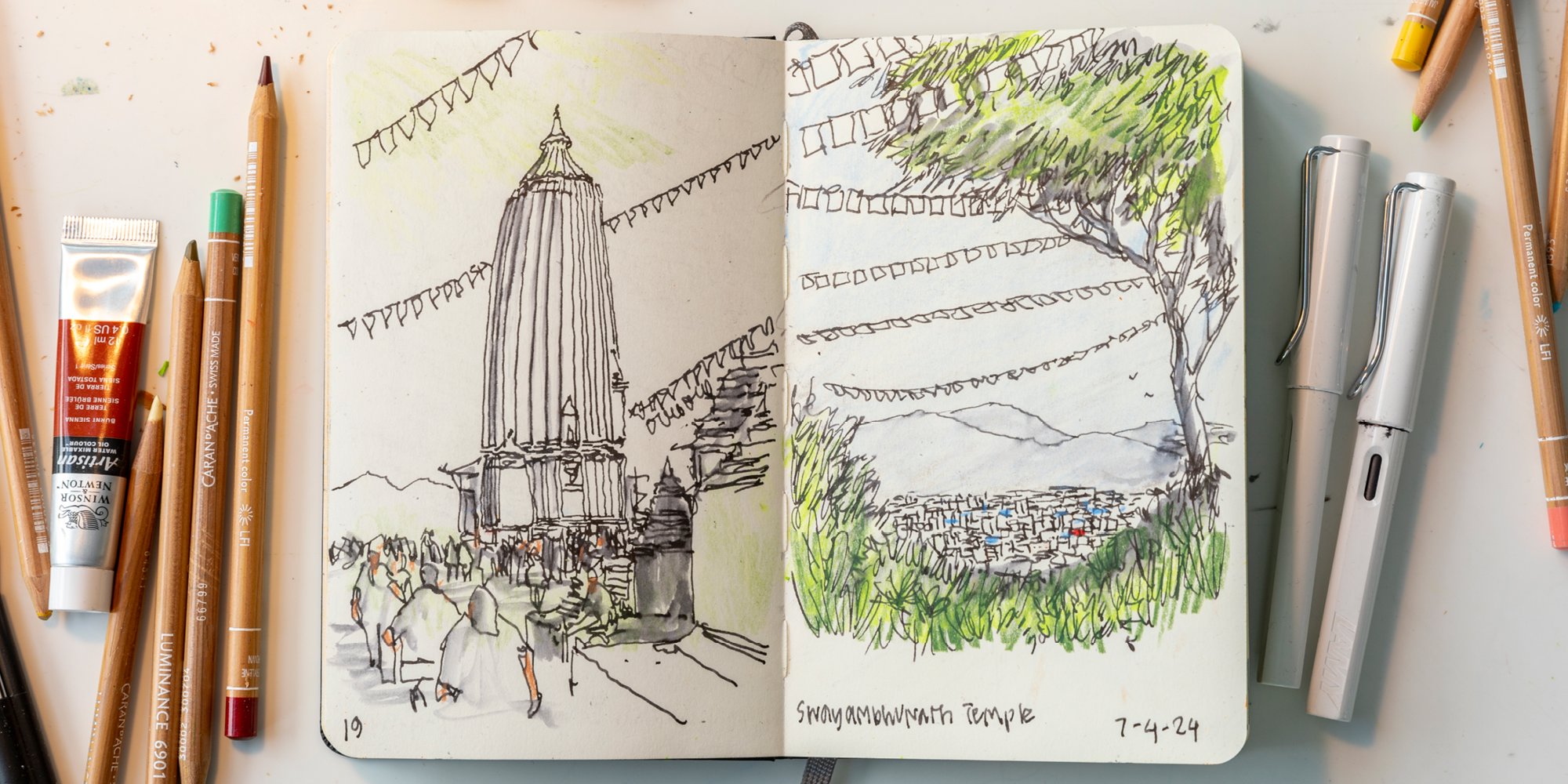

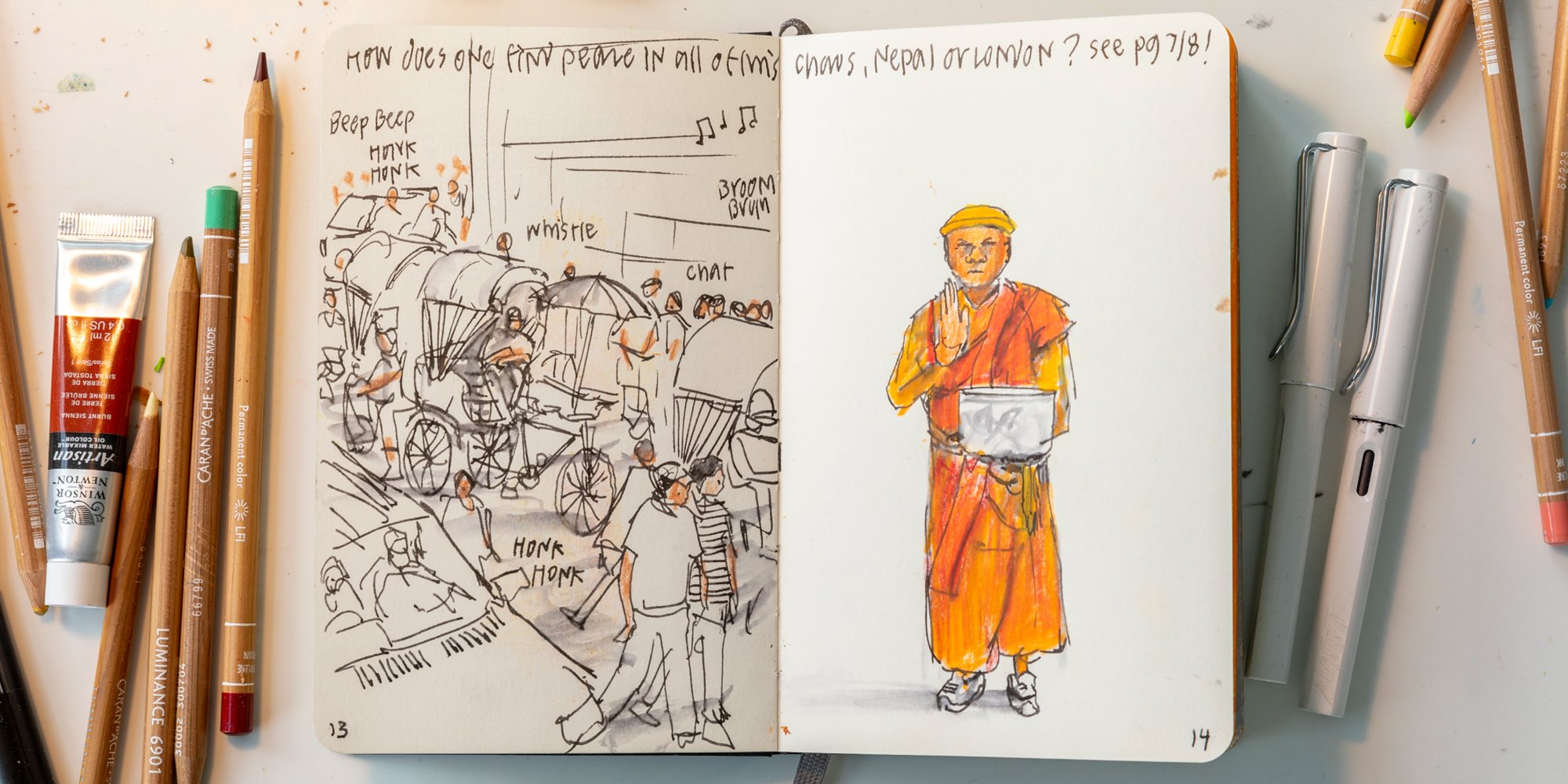

Sketchbook from Narinder Sagoo's recent trip to Nepal in support of [CHARITY NAME]. Sketching, for Narinder, is a tool for creativity and expression that can bypass the constraints of verbal language. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Sketchbook from Narinder Sagoo's recent trip to Nepal in support of [CHARITY NAME]. Sketching, for Narinder, is a tool for creativity and expression that can bypass the constraints of verbal language. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Sketchbook from Narinder Sagoo's recent trip to Nepal in support of [CHARITY NAME]. Sketching, for Narinder, is a tool for creativity and expression that can bypass the constraints of verbal language. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Sketchbook from Narinder Sagoo's recent trip to Nepal in support of [CHARITY NAME]. Sketching, for Narinder, is a tool for creativity and expression that can bypass the constraints of verbal language. © Aaron Hargreaves / Foster + Partners

Similar to storyboarding, sketching is the communal grammar of the team. Members often sketch during conversations and reviews with the architects and with one another – translating between the verbal and the non-verbal, the stated and the implied. This receptivity to sketching allows ideas to germinate and, in turn, to influence and contribute to the design process. The relative freedom permitted by sketching is important for the team. As Nicte reflects:

Many architects in the broader field are quite nervous about drawing – especially on the spot. Perhaps this is because drawing is a skill that is rigorously monitored and graded at university, which can make people self-conscious and block their creativity. You have to know and understand the techniques of drawing, of course, but you also have to develop a confidence that is not necessarily taught. This comes from practice, and from making mistakes – which are never mistakes, but an essential part of the job.

In recording a line of thought, an artist’s sketch can suspend and frame instances where ‘problem’ and ‘solution’ interact, and often be used to ask questions of a design. Within this careful suspension between skill and receptivity to new information, the temporality of the sketch is itself hard to outline. Sometimes, surprises and resonances strike mid-conversation, and a design logic is revealed. However, not all drawings fall into this alluring myth of the architecture ‘napkin sketch’; sketching is more often the outcome of an extended period of intense research and practice or a ‘working out’ stage that transforms and communicates between mediums. Sometimes, a sketch from a different design stage, or a different project entirely, might find relevance and application elsewhere. This is why sketching – and drawing more generally – resists neat temporal frameworks or clear citation. Rather, it represents the continued freedom to question ‘what might be possible’ for a design all stages.

The drawing reveals qualities and relations unimagined beforehand, moves can function as experiments.

Donald Schon, The Reflective Practitioner

For all its mysteries, drawing serves a key function in the practice – as it did when Norman would first sketch in conversations with other architects and engineers. Alongside the architectural, engineering, and visualisation teams (that draw vital components of any design submission), Design Communications bring their specialist training to an architectural scenario in ways that might respond to and influence that design. It is this conversational and reciprocal element that the architectural drawing retains, and that makes it a particularly ‘transitive and communicative’ tool for the practice, both then and now.

Author

Aurelio Cavallaro, Victoria Dykalo, Jordan Hughes, Nicte Loya Chable, Narinder Sagoo, Matthew Simpson

Author Bio

Aurelio Cavallaro is a Senior Artist at Foster + Partners. Beginning his career as an architect, Aurelio's passion for visual storytelling led him to specialise in 3D visualisation. After completing his post-Master Course in Digital Drawing at IUAV in Venice, he began his journey in Berlin, then joined the Design Communications team at Foster + Partners in 2021.

Victoria Dykalo is an Artist Assistant at Foster + Partners. After graduating as an architect from Lviv Polytechnic National University in Ukraine, Victoria began her career in 3D visualisation. She joined the Design Communications team in 2022, and now creates photorealistic artwork for architectural and design projects worldwide.

Nicte-Ha Loya Chable is an Architect and Illustrator, with eight years of experience in the industry. Working as a Artist at Foster + Partners, Nicte combines her architectural knowledge and her passion for drawing by working closely with the designers to translate ideas and concepts to a more visual language.

Jordan Hughes is a Concept Artist and Architect with a decade of experience within the architecture industry; he has gained two master’s degrees in architecture and won multiple international design competitions. Jordan joined the Design Communications team as an Artist Assistant at Foster + Partners in 2022.

Narinder Sagoo MBE, an architect by training, is the Art Director of the Design Communications team and Senior Partner at Foster +Partners. With over 27 years of experience working alongside Lord Foster, Narinder's unique drawing skills have been instrumental in illustrating and communicating architectural visions for numerous projects. Renowned for his perspective drawings, Narinder has produced over 15,000 illustrations for more than 2,200 architectural projects, many of which have been showcased at the Royal Academy of Arts and exhibited internationally, earning him recognition as one of the finest architectural artists of his generation. Beyond his creative endeavours, Narinder is an active Patron for The Big Draw and passionately dedicates his spare time to inspiring the next generation of artists and designers nationally. As an External Examiner at the Bartlett School of Architecture and a member of the RIBA Validation panel for 2008, Narinder continues to contribute to the architectural education landscape. Recently, he has taught at prestigious institutions like Yale University in the USA and the Cambridge School of Architecture in the UK.

Matthew Simpson joined Foster + Partners as an Artist Assistant within Design Communication's newly formed Moving Art team after completing his master’s at the Bartlett School of Architecture in 2023. Working across concept, storyboarding, 3D modelling, Realtime animation, compositing, editing, and musical composition, Matthew applies his understanding of cinema's various tools, methods, and sensibilities to anticipate, imagine, and tell an emotional story to any given project.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George