In conjunction with November’s opening of ‘Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Boundless’ at the Saatchi Gallery in London, +Plus presents an abridged version of Julia Walker’s analysis of the Reichstag in Berlin Contemporary: Architecture and Politics After 1990 (Bloomsbury, 2021). Walker’s feature argues that Foster + Partners’ renovation, like Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s earlier wrapping of the building in 1995, calls upon a strategy of ‘lightening’ to negotiate the Reichstag’s historical gravity. Approaching its 25th anniversary in 2024, Foster + Partners’ renovation of the Reichstag announced a new era for Germany that both acknowledged and transcended the country’s painful political history.

21st November 2023

The Reichstag’s New Lightness of Being

What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness? The only certainty is: the lightness/weight opposition is the most mysterious, most ambiguous of all.

- Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

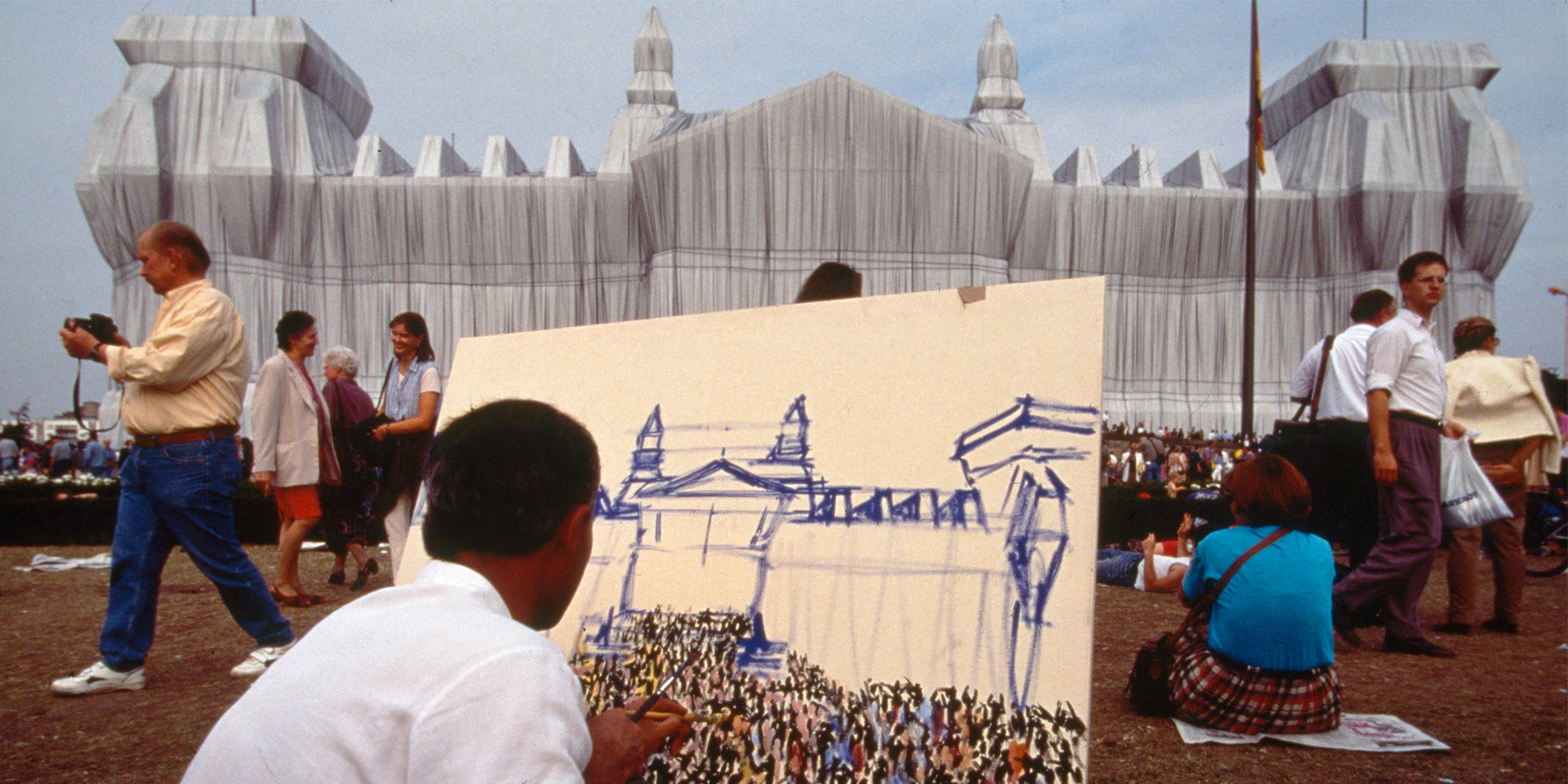

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping of the Reichstag has now become a standard chapter in the narrative of post-1990 Berlin, symbolizing a fresh start for German democracy. For the five million viewers who saw the work in person during its brief existence, it created a jubilant atmosphere and a sense of ease seldom experienced in self-conscious Berlin. For the artists, it was a tribute to the city and its visitors, auguring – so they hoped – a ‘lighter’ future for Germany. And for the British architect Norman Foster and his practice Foster + Partners, who would begin their renovation to make the building over into the seat of the new reunified German parliament the day after the project ended, the wrapping served as an auspicious prelude to his own efforts by establishing the appropriate atmosphere for the building’s renaissance. ‘The mood of the period in which it was wrapped was just unbelievable,’ he recalled in 1999. ‘It was an extraordinary experience, a signal for the transformation, the rebirth, of the Reichstag.’

Ultimately, the wrapping points to the key strategy at the heart of Foster + Partners’ renovation, which entailed posing lightness and both its opposites, weightiness and darkness, as antithetical conditions that could only be mediated by architecture. In the 1990s and still today, this mediation of historical weight was precisely the kind of effect that contemporary architecture aimed to achieve. Various iterations of the building are not merely serial views onto the same object, but rather are fundamentally interrelated instances of how its current significance has coalesced around a discourse of lightness.

A 'light sculptor' at the core of the Reichstag’s cupola reflects horizon light into the chamber. At night, this process is reversed. Beams of light are projected out across the city and the cupola becomes a beacon, signalling the strength and vigour of the German democratic process. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

On Lightness

Architecture itself was to be the means by which historical lightening was attained, both in the Reichstag’s wrapping and in its renovation. To achieve this sense of relief meant translating the idea of philosophical and historical lightness (associated with clarity, openness, and emancipation) into the visual language of architectural lightness. Lightness, of course, stands diametrically opposed both to heaviness and to darkness, and contemporary architects (including Foster + Partners) make use of the slippage between these two antonyms. In the most fundamental sense, weight itself is necessary for architecture to perform its most basic functions and is thus, to some extent, proper to the art. Lightness, therefore, is always a contradiction of architecture’s most immanent qualities; but the movement between physical and metaphorical registers is what marks the Reichstag project – understood broadly, including Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping – as a work of contemporary architecture culture. By designing a cupola formed of glass, facilitating circulation and transparency, and by putting certain physical marks of the past on display, the Reichstag self-consciously pits its historical gravity against its contemporary lightness.

Historical weight: “A building that could not decide what it wanted”

The Reichstag building was initially designed by Frankfurt architect Paul Wallot, and first opened in 1894. However, over the course of its completion, Wallot’s Reichstag had already developed beyond the initial design into a cluttered composition of Baroque details piled atop Renaissance massing. Wallot’s labored effort to synthesize modernity and history fell short; the building merged a hefty columned entrance with stout sculptural figures, and a segmented iron-and-glass dome. This stylistic heterogeneity, according to the Reichstag historian Michael Cullen, created:

A building that presented a different appearance on nearly every façade and yet another different one in the cupola. It was a building that could not decide what it wanted … it became merely an example of the deep division in the German Empire and of a parliament’s powerlessness to become master in its own house.

Over the course of the twentieth century, the Reichstag’s architectural reputation did not improve. It invoked several historical languages but seemed to speak none of them fluently; though it did not rise in architectural esteem, it nonetheless collected considerable historical baggage. It acted as a built bookend for the volatile Weimar Republic, proclaimed from its balcony on November 9, 1918 and ended by the calamitous fire of 1933 that enabled Hitler’s dictatorial power-grab. After the fire, the collapsed dome was reglazed but the building was only partially restored, a physical reminder of the utter futility of the Reichstag as a governing body under National Socialism. Soviet soldiers took particular aim at the building during the Battle of Berlin, after which the building slumped in a state of ruin for fifteen years. The dome was finally demolished in 1954, having been declared a public hazard.

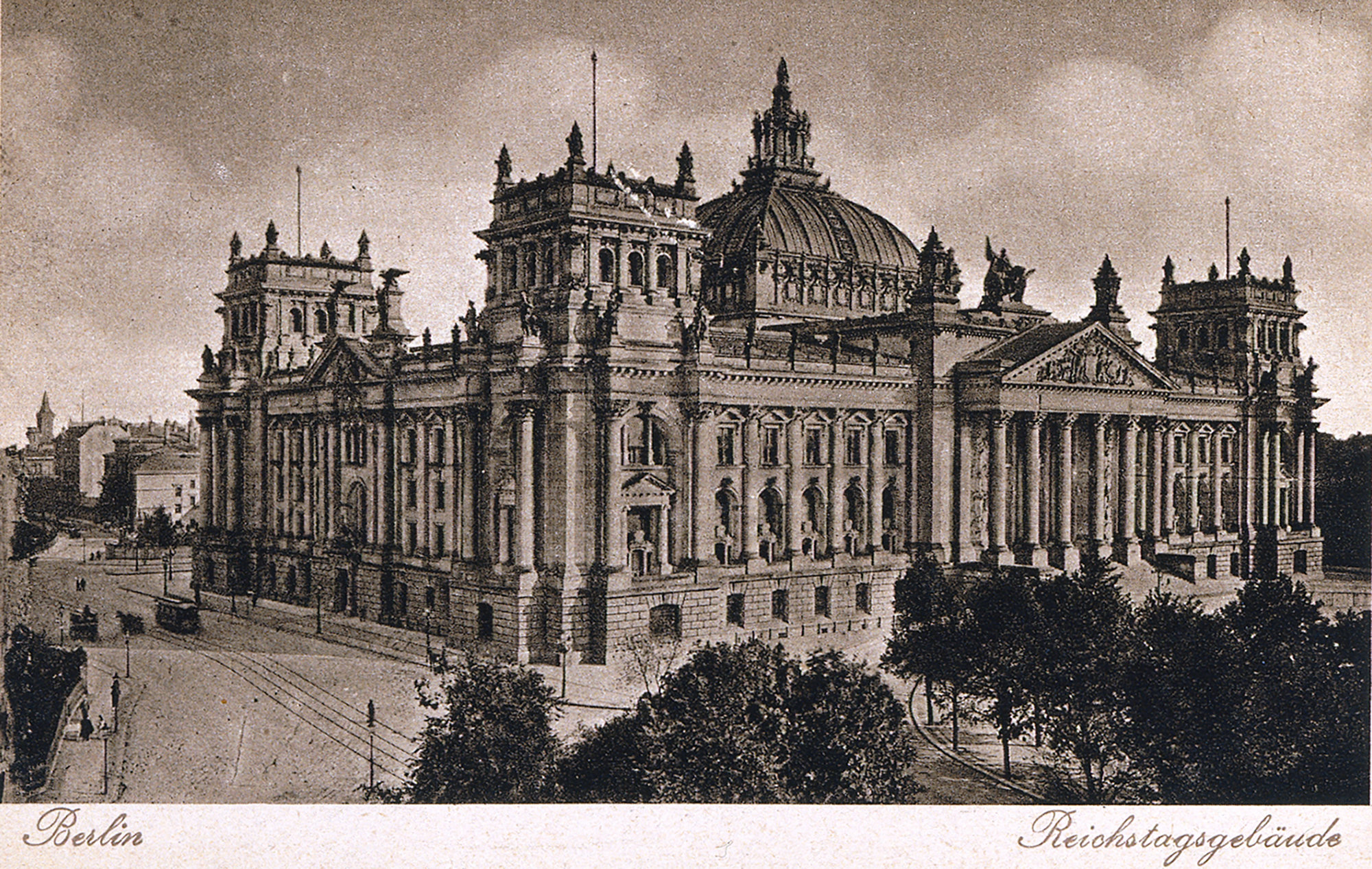

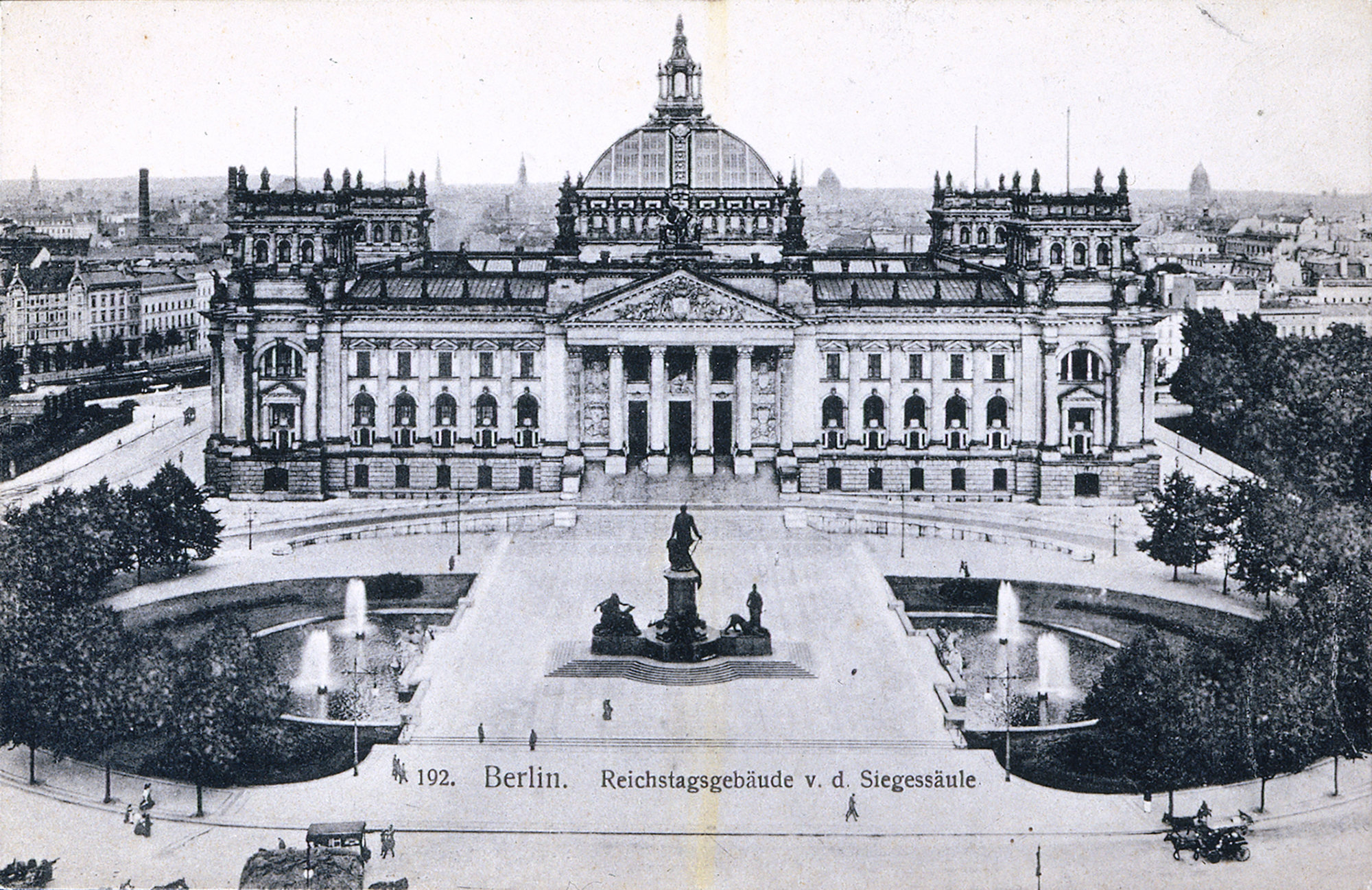

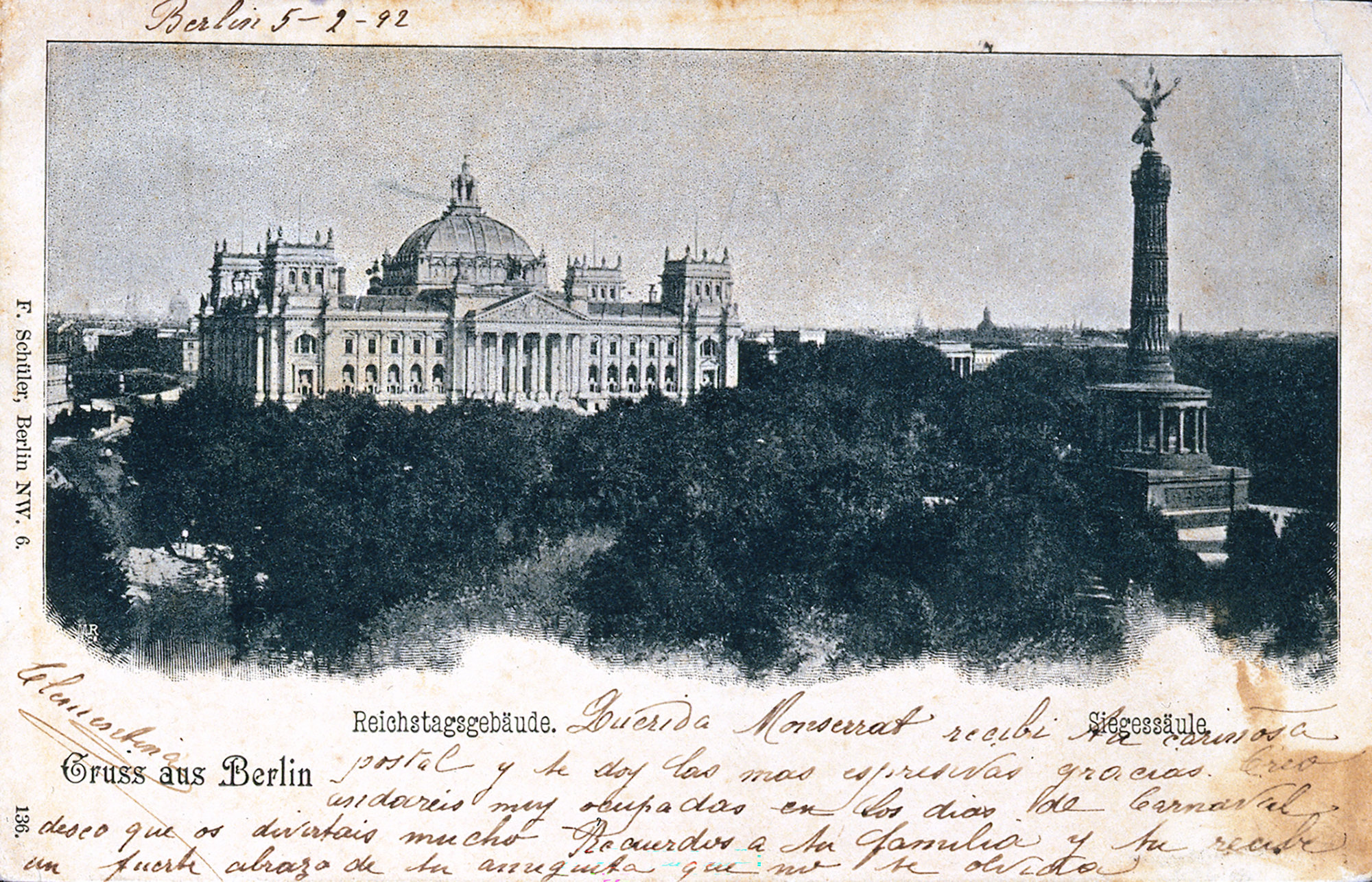

A series of nineteenth-century postcards of the Reichstag, collected by David Nelson, Head of Design, Foster + Partners.

A series of nineteenth-century postcards of the Reichstag, collected by David Nelson, Head of Design, Foster + Partners.

The post-war years saw little resolution for the Reichstag’s use. In 1961, Paul Baumgarten refurbished the structure as the hopeful future home of the Bundestag. The renovation gutted the Reichstag’s damaged interior and covered its ceilings and walls with plasterboard. Ineffectual even to his own eyes, Baumgarten’s rehabilitation failed to endear the building to the public. It was in this condition that Christo and Jean-Claude first encountered the building, and, decades later, it was in this condition that it was wrapped.

Contemporary lightening: Wrapped Reichstag

Despite its present-day association with the politics of reunification, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s project had in fact been under development since 1971. The Reichstag’s position on the border between east and west rendered it, at least provisionally, an impossibility. It was only after reunification in 1990 that the work’s realization became feasible, leading to intensifying emotions as that feasibility increased. It faced serious opposition from powerful government officials. Interest in the project ran so high that the unusually impassioned debate in parliament over whether or not to approve the project was televised to the entire European Union. Peter Conradi (who was also a vocal supporter of Norman Foster) convinced his peers during discussion preceding the vote that the wrapping of the building would ‘send a positive sign, a beautiful, bright signal, that offers courage and hope and radiates self-confidence.’ The Bundestag voted 292 to 223 in favor of the wrapping.

Although critics debated the import of the project without consensus, most agreed that Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping was alchemical, transforming the building from a grandiloquent fossil into Berlin’s most stunning (and stunningly contemporary) attraction. Paul Goldberger reported in The New York Times that ‘this immense stone hulk, a heavy, bombastic building that epitomizes German excesses of the late 19th century, is rendered light, almost delicate.’ To Goldberger, the dialogue underlying the work was one between impossibly polarized terms; and indeed, the otherworldly effect of the wrapped Reichstag turned on its ability to transform the building into its apparent opposite – from hard to soft, from permanent to ephemeral, from monumental to fragile.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping was alchemical, transforming the building from a grandiloquent fossil into Berlin’s most stunning (and stunningly contemporary) attraction.

On July 7, 1995, after a run of only two weeks, Christo and Jeanne-Claude – refusing to extend the exhibition, despite exhortations from the public – disassembled the polypropylene and the steel skeleton that supported it, leaving the work to circulate in their trademark ephemera of drawings, photographs, and videos. The following day, demolition began on Baumgarten’s interiors to clear the way for Foster + Partners’ renovation. The stage had been set for the unveiling of their radiant, undeniably contemporary cupola, hovering ethereally over the building like a beacon of democracy.

“The Big Roof”

A competition for the building’s reconstruction was held in 1992. Though it is strikingly different from the final building, Foster + Partners’ discarded proposal nevertheless reveals many of the strategies of global contemporary architecture on view in the Reichstag as it was constructed. Out of many proposals, three projects – all by foreign architects – were initially awarded a joint first prize. Each proposed radical solutions to the Reichstag, all of which would have the effect of placing the historical building inside a viewing frame.

Pi de Bruijn, of the Amsterdam group de Architekten Cie, offered a project that drew openly on Oscar Niemayer’s National Congress for Brasília, in which a bowl-shaped plenary chamber rested on a podium in front of the Reichstag like a piece of public sculpture. Along the northern perimeter of the site, a horizontal strip would house the presidential wing, appearing almost as though one of Brasília’s twin parliamentary towers had been turned on its side and cut open for pedestrian traffic. The historical Reichstag was partially submerged in the raised podium, thus becoming another object in this catalog of historical references.

The Spanish-Swiss engineer and architect Santiago Calatrava’s competition entry likewise invoked modernist precedents, but with a lyrical expressionism absent from de Bruijn’s cerebral modernist citations. Calatrava proposed to rebuild the Reichstag’s interior in crystalline glass and reconceive the dome as four segmented glass shells floating above the plenary hall. These shells would open and close slowly like the petals of a flower, which he hoped would negate the building’s painful history, projecting instead a sense of openness, airiness, and naturalness. This ruin-gazing lens is elegiac but nonspecific, romantically juxtaposing the old and the new in a treatment of historic architecture that is common in contemporary architecture culture.

Yet it was the third finalist, Foster + Partners, to whom the Bundestag would eventually award the commission. Describing his proposal for the Reichstag, Foster proclaimed that the building ‘could not shed the weight of its past associations but it had to be lightened symbolically,’ and this drive for lightness infused his response to the competition brief. Rather than enhancing the existing Reichstag building with major flourishes, Foster + Partners’ proposal conceptualized the old structure as the anchoring element of a raised plinth that created an area for public gatherings and reduced the bulk of the building from the ground level view. Although its proposal predated the actual wrapping of the Reichstag, the resonances in the atmosphere Foster + Partners’ intended to create around the building and those resulting from Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installation are conspicuous.

A 1:200 model of the Reichstag first-stage competition scheme with its oversailing canopy as seen from the north bank of the Spree. © Richard Davies

A translucent roof covered the circular plenary chamber, allowing visitors on the roof to peer inside during parliamentary debates, and an interior atrium surrounding the plenary chamber would create further publicly accessible space. Furthermore, the historical building itself was sited asymmetrically within the plinth and was intended to be just one component in an entire urban ensemble that would include theaters, cinemas, galleries, bookshops, riverside cafes, schools and daycares, and abundant underground parking for public use.

This lively public forum would be sheltered beneath what Foster termed ‘the big roof”—an immense, translucent canopy 250 meters long and 160 meters wide, intended to serve both practical and symbolic purposes. Functionally, the canopy would have played a crucial role in making the building ecologically sustainable, since its square panels would be implanted with photovoltaic cells to harvest solar energy and would permit diffused natural light into the building’s interiors. Symbolically, Foster and supportive Bundestag members believed that the canopy effectively united the old with the new, as well as lightening the mood of the existing building.

It was not to be. Despite its enthusiastic reception, Foster + Partners’ ‘big roof’ was slated for the cutting-room floor. In the first place, it conflicted spatially with Axel Schultes’ and Charlotte Frank’s master plan for the government district. Furthermore, economic pressures nationwide forced the Bundestag to reduce the budget for the building’s reuse by a drastic percentage and to condense the necessary space from 33,000 square meters to between 9,000 and 12,000.

In architecture, the political ideology of transparency has most often been expressed through the materiality of glass, which renders buildings visually penetrable and phenomenologically open.

After the original proposal, the form of the renovation changed utterly, but the essential strategy of lightening remained consistent throughout. Following several design phases, Foster + Partners began to examine possible forms for a new dome. Eventually, the Bundestag officially approved the renovation plans, whose primary exterior alterations included the glazed entrance façade and the now-acclaimed cupola, a transparent, ovoid volume whose steel oculus and ribs support the dynamic curl of the spiral ramp. Inside the cupola, a fountain-like mirrored cone issues from above the plenary chamber before cascading into the glass panels that comprise the dome’s exterior.

In architecture, the political ideology of transparency has most often been expressed through the materiality of glass, which renders buildings visually penetrable and phenomenologically open. The use of large expanses of transparent glass in architecture amassed meanings during the twentieth century that connected it, however loosely, with moral clarity, progressive social values, neoliberal economic policies, and permeable borders. Foster + Partners’ glass cupola thus extends the ideology of transparency while aiming to revitalize the concept for the Berlin Republic.

The practice’s proposal for the Reichstag, furthermore, serves an ecological as well as ideological function, decreasing the building’s carbon footprint and thus representing a different form of “lightness”—sustainability. In his view, the sense of ecological lightness resulting from minimalistic, environmentally high-tech architecture is both ethical and humanistic. His mentor Buckminster Fuller, a pioneer of lightweight tensile structures and passive sustainable designs, once famously inquired of him, “How much does your building weigh, Norman?” To Fuller, the calculation of the weight of a building involved its consumption of resources, the overall mass of its materials, and the stress it exerted on fragile ecosystems. But alongside these hard calculations, Fuller also contemplated the poetics of sustainability, investigating the metaphysical conditions under which humans could exist in harmony with their natural surroundings. Under Fuller’s influence, Foster continued to investigate the potential of high-tech design to actualize ecological lightness, and this green approach to design has been a hallmark of his career.

Faith in Graffiti

Since the process of amending Foster + Partners’ plan began, most critical and popular attention has remained focused on the vexed question of the dome. Yet for all the literal and figurative high visibility of the cupola, perhaps the aspect of the studio’s project that more fully reveals its strategy of reframing the Reichstag as a model of contemporary lightness has received little sustained scholarly treatment: its insistence on conserving the graffiti left by Soviet soldiers passing through the Reichstag during the Battle of Berlin. After the demise of the canopy scheme, it was these graffiti that provided the necessary pendant weight to accomplish Foster + Partners’ sought-after lightening, allowing Foster to pronounce the Reichstag a ‘living museum of German history.’

The details of the renovated Reichstag call for the viewer to touch the graffiti, a haptic invitation that Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Reichstag issued as well.

According to Foster, his studio’s conviction that the graffiti must be preserved was more or less immediate upon its discovery. Their reasoning was straightforward: to erase or cover these marks, they argued, would be to obfuscate the historical events that the Reichstag building documented. Parliamentarians voiced vehement positions. After a series of debates, a narrow majority voted to preserve nearly all the remaining graffiti.

Here the walls and niches of the north corridor carry the scars of war – broken stones and Soviet graffiti – but also those from the 1960s, when all the ornamental carving was chiselled away. Suspended steel bridges inserted in the corridor at mezzanine level allow access to the public and press tribunes in the chamber, their lightweight forms a counterpoint to the heaviness of the existing masonry. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The decision to maintain the inscriptions came at considerable expense, especially at a moment in which the Bundestag was cutting budgets for building projects across the capital city. With no real precedent available, the Fosters team had to improvise the technology necessary for the graffiti’s conservation. Stabilizing the fragile marks meant going over each line with a fixative (thus uncannily recreating the original gestures of inscription), then cleaning the negative space by tracing the area around each letter with a minuscule sandblaster. Photographs documenting the process of conservation show hard-hatted and goggled workers in front of the walls with pencil-sized implements in their hands, contemplating the graffiti like artists poised to make the first brush stroke of a masterpiece painting. Other images show workers on ladders or scaffolds, like conservators tending the frescoed interior of a church. This obsessive level of detail – the artisanal slowness of the process of conservation, in contrast to the speed with which the graffiti were originally scrawled – imparts a sense of handcraft to Foster + Partners’ otherwise high-tech renovation. Like much of contemporary architecture, the Reichstag reveals a surprising nostalgia for the bodily intimacy of craft as manifested in ornament.

In this way, the graffiti also act to validate the Reichstag’s historical significance, positioning the building as a reliable and objective eyewitness to the events of the past. The renovated building bears these inscriptions along with other emblems of its age, such as fragments of original moldings, mason’s marks, and even bullet holes. These ‘scars of damage and disruption,’ in Theodor Adorno’s words, act as a ‘seal of authenticity,’ corroborating the building’s narrative of a trauma overcome. In fact, it is the corporeal intimacy of the graffiti, the way in which each mark supposedly retains the indexical power of human touch, that allows it to fulfill this authenticating function. The role of architecture, then, is to facilitate this closeness, allowing the audience to ‘experience’ the marks of history on view. Many critics, and Foster himself, have noted that the details of the renovated Reichstag call for the viewer to touch the graffiti, a haptic invitation that Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Reichstag issued as well.

Architect as Historian

Foster + Partners’ renovated Reichstag demonstrates that the very idea of historical transparency belongs to the contemporary. The contemporary architect’s concern, therefore, is not only design, but also the amassing, selection, and distillation of historical information. Using ‘authentic’ elements of the past, the historian-architect makes a claim to objectivity that is in itself a romanticizing narrative of history. That story then forms the basis of a new national myth, emphasizing cultural rather than political unity and soft power as gentle as Wrapped Reichstag’s billowing fabric. But perhaps this fusion of objectivity and romanticism is one of contemporary architecture’s most important functions, fostering the belief that glass walls and steel frames can make history tangible, knowable, and ineradicable. If we believe such buildings, they will tell us the truth; if we believe in them, then the past will remain ever-present – in other words, the faith of contemporary architecture.

Author

Julia Walker

Author Bio

Julia Walker is Associate Professor of Art History at The State University of New York at Binghamton, USA. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary architecture, emphasizing the persistence and transformation of modernist ideas within contemporary practice—and the ways in which this modernist inheritance informs, inflects, and destabilizes claims to political meaning. Her current projects examine the underrepresentation of women in architectural practice and explore the history of architectural criticism as a genre.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George