For 170 years, the site of the Transamerica Pyramid has been a witness to and a catalyst of San Francisco’s social and cultural history. Irma Delmonte, architectural researcher at Foster + Partners, considers how this unique history was centralised in the developing masterplan and restoration of the site.

14th March 2023

Story of a City Block: Foster + Partners and the Transamerica Pyramid

Transamerica then, Transamerica now

Architectural history admits to certain patterns – one rule being that any city landmark that is considered iconic today was once heavily criticised. St Paul’s Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, the Sagrada Familia, the Empire State Building, the Golden Gate Bridge: all were met with suspicion and resistance; all were daring visions that had as many detractors as supporters.

Designed by American architect William Pereira (1909-1985), the 260-metre- (850-foot-) tall Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco is one such building. It marked a moment for San Francisco – a time when the city was negotiating both its heritage and developing identity. Following its construction in 1971, and its consequent status as the tallest skyscraper in the city, the Transamerica was debated extensively. It was hated by some: the San Francisco Chronicle dubbed it ‘the world largest’ s architectural folly.’ It was embraced and defended by others; the city’s mayor, Joseph Alioto, argued that the building captured ‘that spirit and daring that make us perhaps a little different – a spirit and daring that welcome individuality and diversity.’

“It is this ‘spirit and daring’ that the client SHVO and Foster + Partners researched and expressed in their recent masterplan of the Transamerica site. Through considering the history preceding the Transamerica Pyramid’s design by Pereira, the true richness and depth of the team’s vision of the future of the Transamerica can be fully understood. The result: a masterplan that deftly blends an historical sensitivity to a place’s ‘spirit’ with technological and environmental innovation.”

Creative re-use during the Gold Rush

Today, the San Francisco Bay area – the epicentre of the global tech industry – is an incubator of innovative and creative thinking. This follows its well-documented modern history as a counterculture haven for artists, architects and writers. However, it was over a century earlier, in 1849, following the discovery of gold and the subsequent Californian Gold Rush, that the city’s now famous spirit was beginning to take hold.

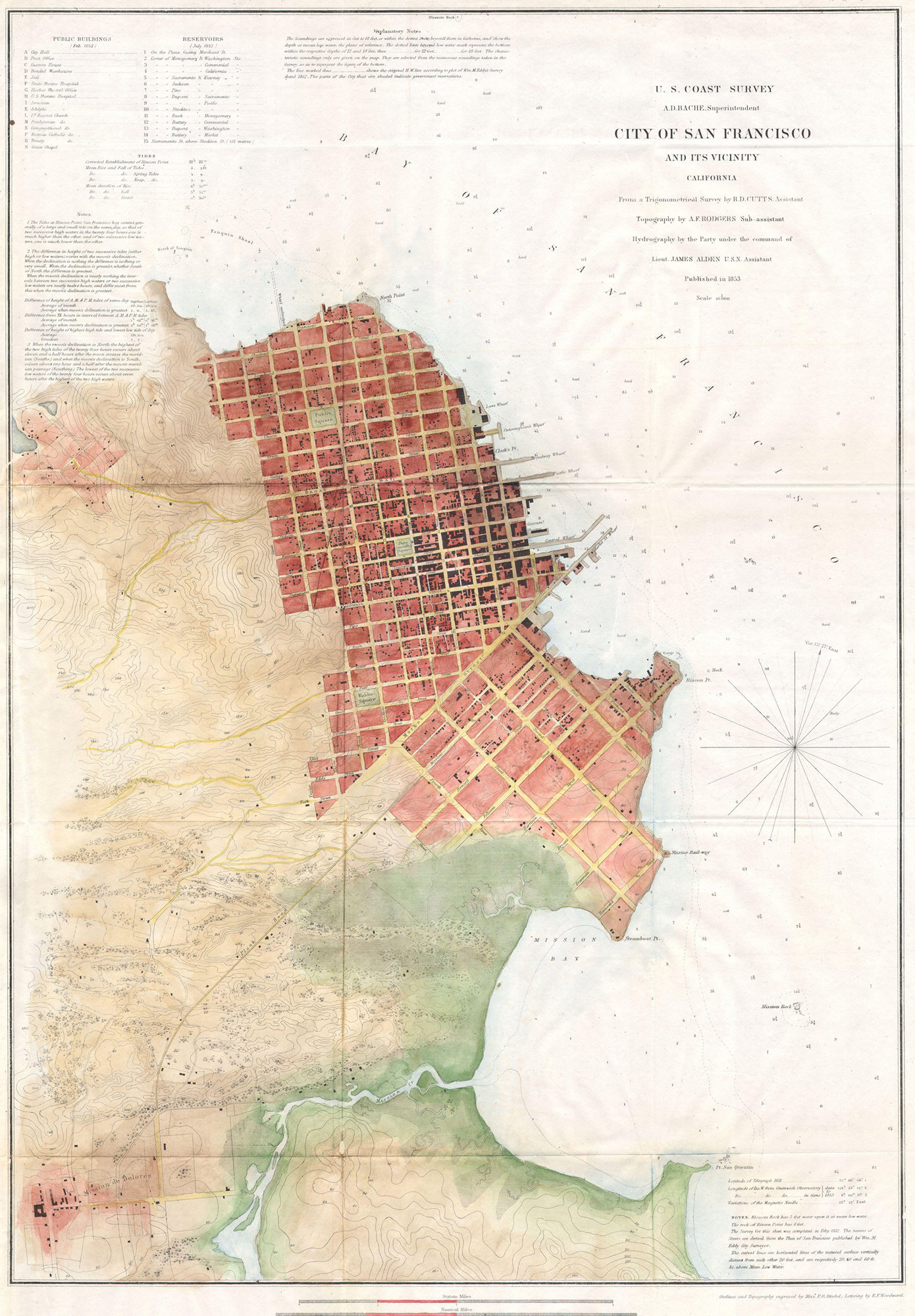

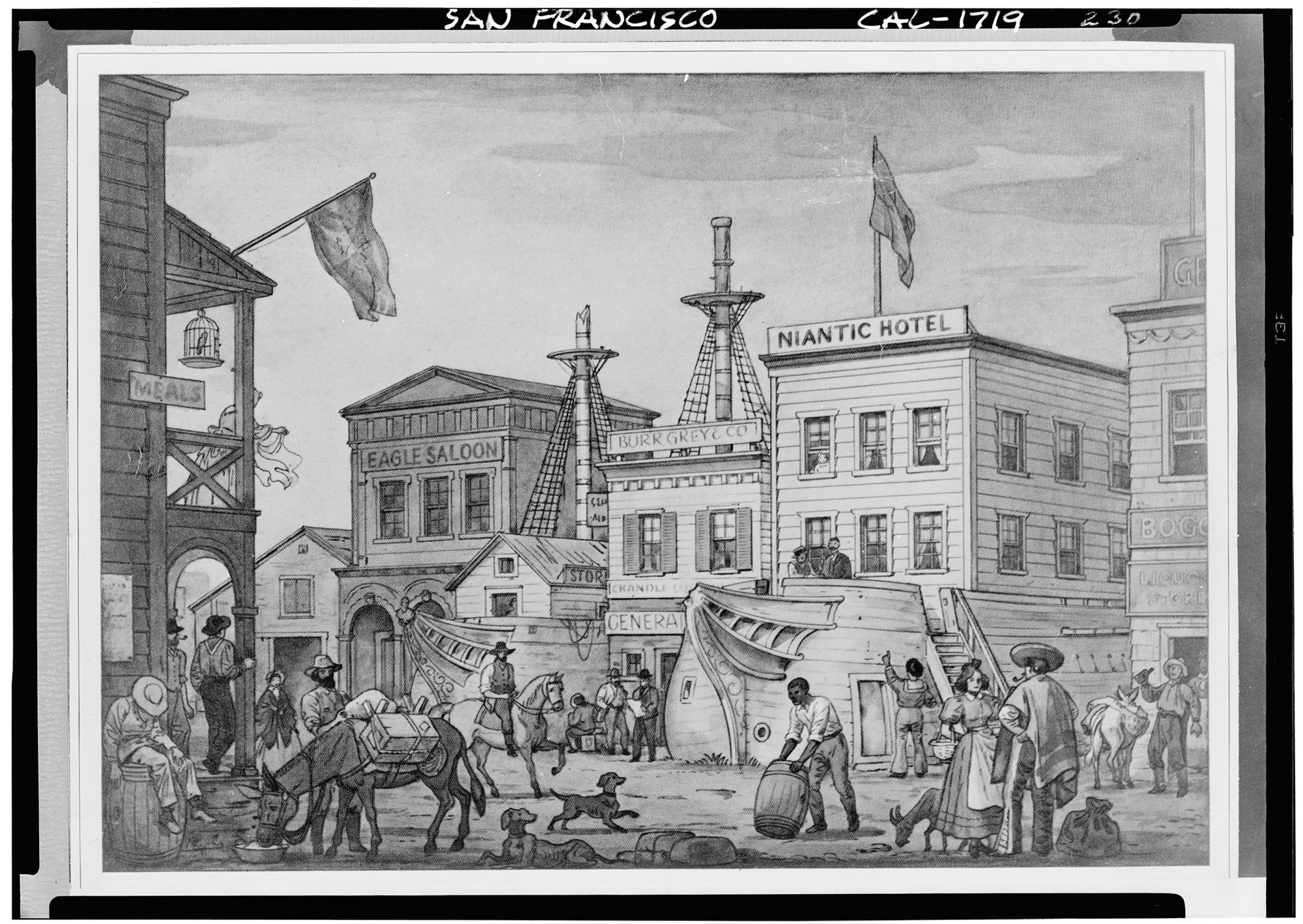

Yerba Buena Cove was a coastal inlet where a small village, Yerba Buena, was located – the germination of the city known as San Francisco. This site was one of several in the bay area that was inundated with ships, brigs, and barks. The beach of the cove was set back as far as what is now Montgomery Street between Clay and Washington Streets. Vessels, abandoned by their crews and officers (in favour of digging sites nearby), were bought from a master or owner's agent. Beached or scuttled in the shallow waters of the cove, a hull was transformed into a warehouse, hotel, restaurant, tavern, or store. Ships became floating buildings, wharves became streets. Such conversions were far quicker and less costly than buying a plot of land and hiring construction workers at premium rates.

The story of the Transamerica Pyramid springs from this culture, beginning with a vessel called Niantic. Once a whaling boat and a storeship, Niantic sunk offshore at what is now the intersection of Clay and Montgomery Streets, the current site of Transamerica. The rest of the ship, no longer needed for its original purpose, was creatively re-used as a warehouse, store and offices – an early example of a cost-effective, sustainable and adaptive way of building. During a series of fires between 1850 and1852, it repeatedly burned and was rebuilt as the Niantic Hotel, looking less like a ship each time. The hull of the Niantic has been rediscovered several times during the last century: firstly, after a city-wide fire in 1906, then again in 1978 during an excavation for the Mark Twain Alley (now at the Redwood Park). Its site, where the Transamerica Pyramid now stands, is marked by a plaque as a California Historical Landmark and a portion of Niantic's hull and rudder currently reside in the San Francisco Maritime Museum. It was on this site that Montgomery Block and, eventually, the Transamerica, was built.

Artistic Influences

The Transamerica site was not only an accelerator of urban and architectural metamorphosis, but also a hub for international creatives since the 1870s, largely owing to the development of Montgomery Block. In 1853, when the San Francisco shoreline was positioned at the edge of Montgomery Street, Henry Halleck built a block – also known as Halleck’s Folly – on a marshy land with redwood logs and the old ships below. Montgomery Block quickly filled its courtyards and halls with lawyers, scientists, engineers and bankers willing to rent offices. On the south-west corner of the block (the current corner of Montgomery and Washington streets) a Bank Exchange saloon was set up. It was here that the American writer Mark Twain (1835-1910) drank the city’s famous Pisco Punch (a mix of pisco brandy, pineapple and lime juice), invented by the saloon’s owner, Duncan Nicol.

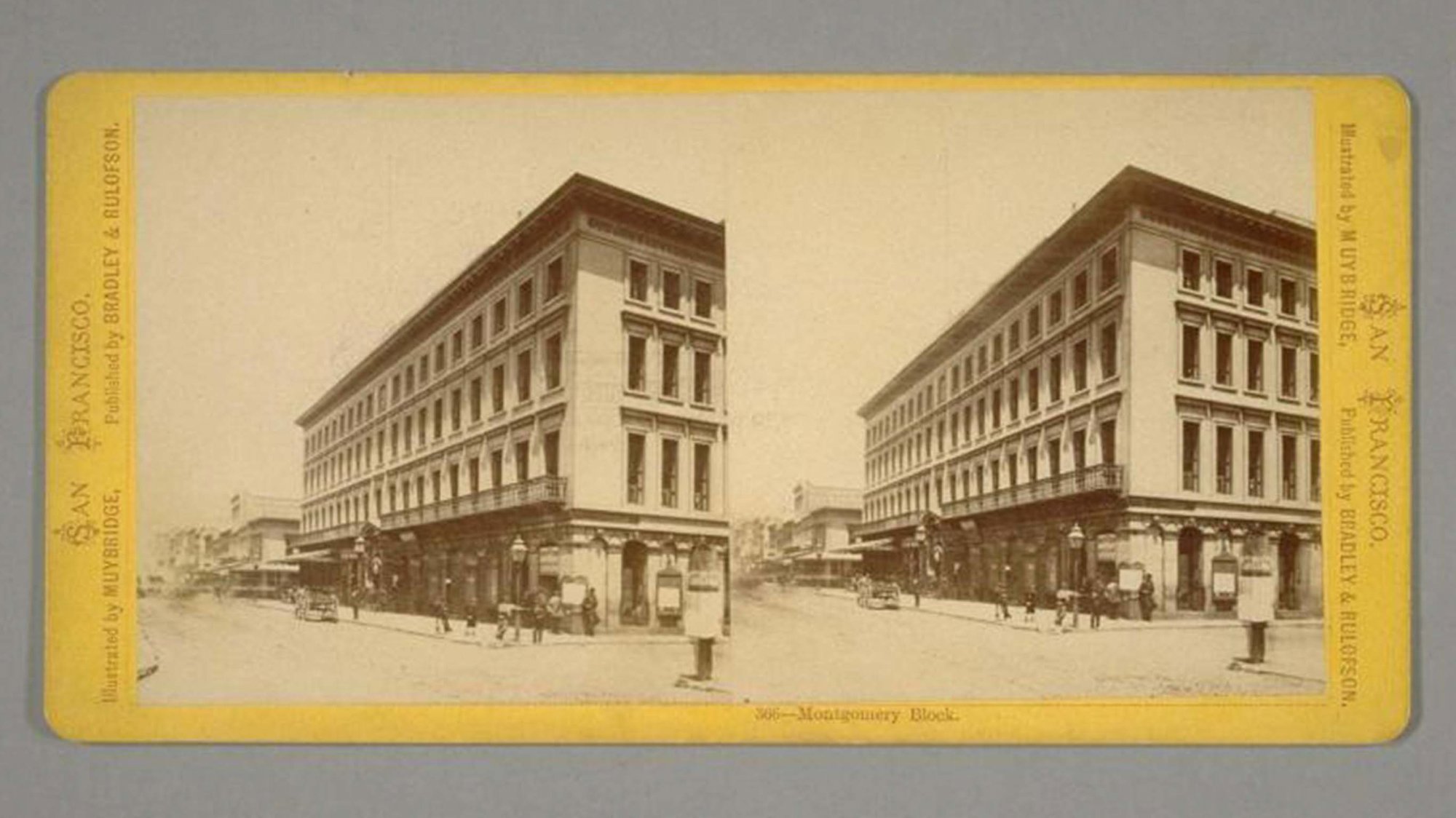

Montgomery Block by Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), the noted English photographer and pioneer of photographic studies of motion and motion-picture projection. Muybridge shot a famous combined thirteen-photograph panorama of San Francisco, where he lived for five years at 113 Montgomery Street. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library.

In the late 1870s, the business centre of San Francisco shifted south down to Market Street and a new era of tenants moved in. Thousands of writers, painters, photographers, sculptures, filmmakers, and musicians rented studios in Montgomery Block from the 1870s until the building’s demolition in the 1959. During those decades, Montgomery Block became the bohemian centre of the West Coast, establishing an artistic hub never seen before in the city.

Montgomery Block became the bohemian centre of the West Coast, establishing an artistic hub never seen before in the city.

Located on the ground floor of Montgomery Block, Coppa’s restaurant was the most famous bohemian haunt. The walls were covered in murals including one titled Bohemian Wall of Fame by Californian artist Xavier Martinez (1869-1943), which depicted famous writers and artists throughout history, ranging from Dante in the Thirteenth Century to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), and even contemporary locals like the American poet and playwright George Sterling (1869-1926). These murals were the manifesto of this leading bohemian generation, alongside a prolific production of poetry magazines, photographs, and music. In San Francisco, writers and artists were allowed room to breathe; it was the spirit of bohemianism held within the walls of Montgomery Block that cultivated such spaciousness.

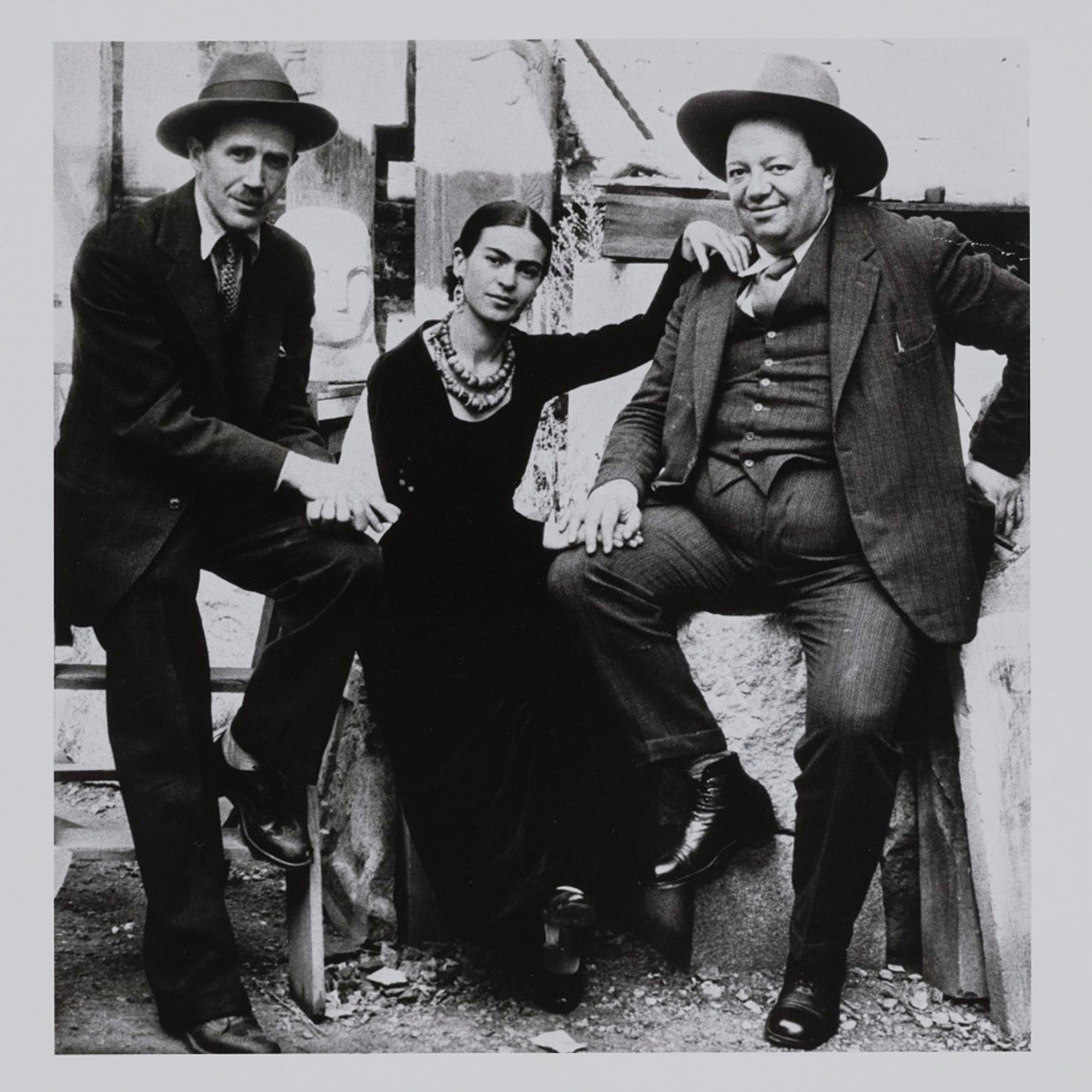

Photograph of American artist Ralph Stackpole (1885-1973), left, with Mexican painters Diego Rivera (1886-1957), right, and Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), centre, at Stackpole’s studio in the Montgomery Block, 1931. Emmy Lou Packard Papers, 1900-1990. Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Foreshadowing its high-rise successor and the present-day commission of an innovative studio like Foster + Partners, the Montgomery was architecturally and technologically advanced. For this reason, it was one of the few buildings to survive the 1906 earthquake and fire that destroyed most of downtown San Francisco. It continued to attract artists throughout (and despite) the Great Depression; Rivera and Kahlo resided there; the Beat generation followed. Montgomery’s spirit of anarchy, of countercultural radicalism, had been present from its beginning, as captured in the work of Twain – until the block was demolished in 1959 to build a parking lot.

Reimagining the office block

On the site of the demolished Montgomery Block, a plan for the Transamerica Pyramid, an owner-occupied building for the Transamerica insurance company, was proposed by Pereira’s architectural studio. The iconic Pyramid form was first conceived in the late 1960s when the CEO of the Transamerica Corporation, John Beckett, visited Pereira’s office to explore an office tower design for its San Francisco headquarters. He saw in the studio a model of a pyramidal structure for the American Broadcasting Company that was initially intended for a site at 66th and Columbus Avenue in New York. Beckett was enthralled, imagining the pyramidal form as a dramatic new corporate symbol for the company.

Above all, a corporation’s headquarters needed to represent and house the ideals of its owners and their affairs. Corporate clients throughout history would commission the best architects to design their headquarters; many classics of the Modern Movement were born as a result, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Lever and Seagram building (1958) in New York, Gio Ponti and Luigi Nervi’s Pirelli Tower (1961) in Milan, or the Willis Faber & Dumas building in Ipswich – designed by Foster + Partners (then known as Foster Associates) in the 1970s. In the USA in particular, corporations were instrumental in shaping the development of office architecture, requiring architects to closely reflect the organisation in its building. Key examples include Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building (1904) in Buffalo and the Johnson Wax Company (1939) – one of his most notable and inventive projects.

The Pyramid received a favourable response from the Transamerica Corporation. However, the citizens of San Francisco were slower to agree. Dozens of residents protested the construction zone in pyramidal dunce caps; the Chronicle’s architecture critic testified against the building at City Hall; San Francisco’s own city planner called the tower ‘an inhumane creation’, ‘hideous nonsense’, ‘authentic architectural butchery’, and ‘an affront to San Francisco.’

Today, of course, the Transamerica Pyramid is an icon within San Francisco’s cultural and architectural heritage. This is arguably due to the clarity of its original design. Pereira’s goal was to create a building of simple, classical form that delivered a graceful silhouette with minimal obstruction to the skyline. At that time, more standardised office buildings in American cities were characterised by a repetitive fenestration system. Rejecting the ‘notion that all buildings must be a cube’, Pereira departed from the common rectangular shape of International Style and Modernist traditions found in San Francisco’s Financial District.

Pereira’s goal was to create a building of simple, classical form that delivered a graceful silhouette with minimal obstruction to the skyline.

Pereira and Foster: simultaneous innovation

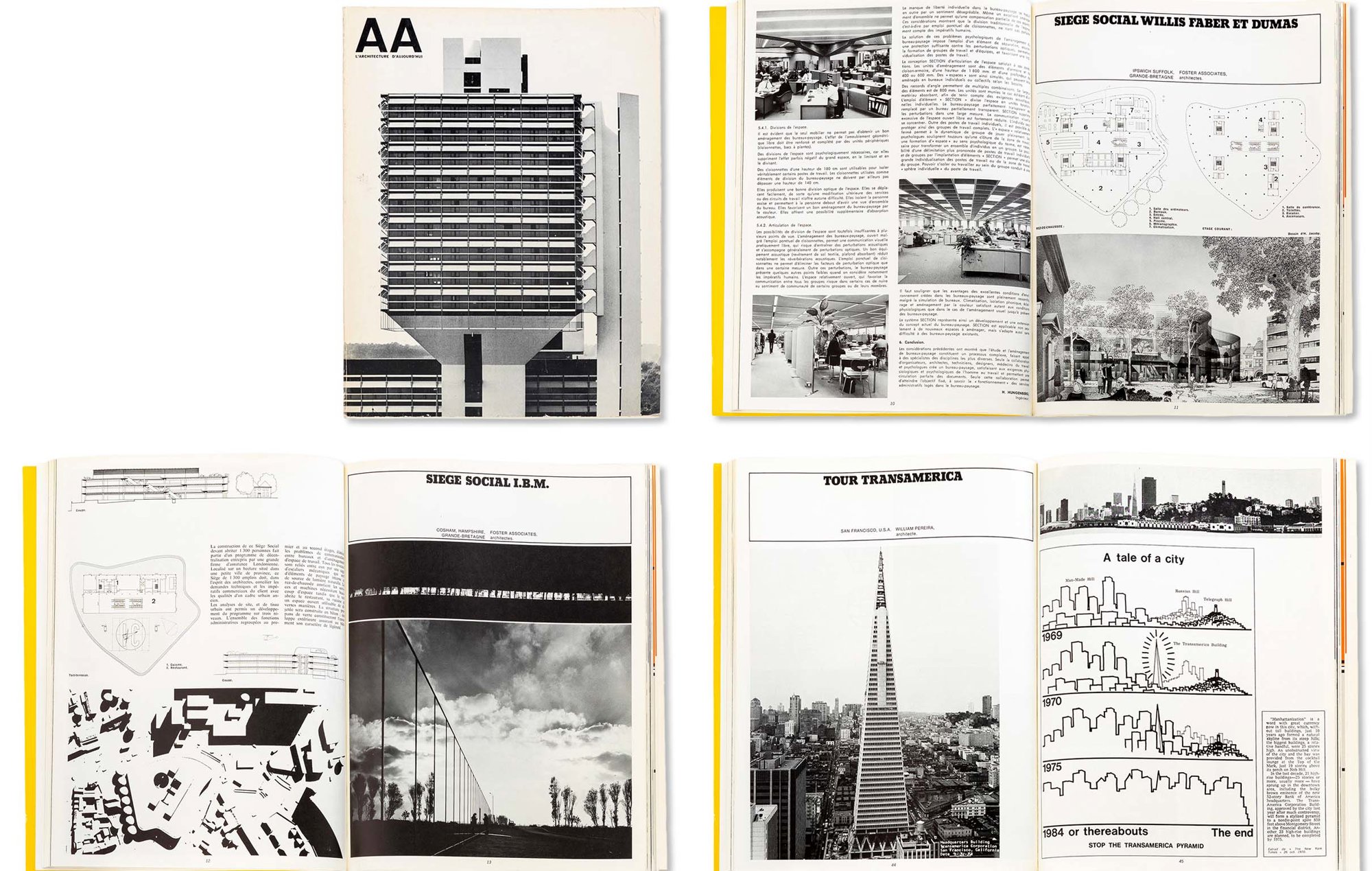

This innovation of office-based architectural form was noted in contemporary publications. In January 1973, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui collated architectural projects that had successfully redesigned ‘Environment du Travail’ (The Working Environment). Foster Associates’ Willis Faber building in Ipswich, UK, and IBM Pilot Head Office in Cosham, UK (1971), were printed in this edition, closely followed by images of Pereira’s Transamerica Pyramid and an essay by Jean-Pierre Cousin on the symbiosis between working conditions and office design.

The publication of Foster Associates’ and Pereira’s projects in the same volume hints at their buildings’ shared qualities: they are commissioned by corporate clients that inspire the values of the design; they carefully consider the interventions and continuations that the buildings effect on the site; they all design with accessibility and indoor-outdoor connections in mind, enhancing the experience of the building’s user.

As shown in the pioneering Willis Faber and IBM projects of the 1970s, Foster + Partners actively pursues research and development programmes through its commissions. Over the decades, as technologies and agendas have evolved, this has manifested itself in different ways. For example, the diagrid structure developed for the Hearst Tower in New York (a steel-core building with a diagonal perimeter system forming four-storey-high triangular frames) emerged as a very practical solution because it provides greater strength and greater structural redundancy.

Completed in 2006, the tower is the headquarter of the Hearst Corporation and used 20 per cent less steel than a conventional post-and-beam structure – a saving of approximately 2,000 tonnes of steel. It was also designed to use 25 per cent less energy than it would had it minimally complied with the respective state and city energy codes. This has earned it a gold certification under the US Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED). It was the first occupied building in New York to receive this certification and since earning that prestigious honour, the building also received LEED Platinum certification in 2012 for operations and maintenance. These achievements reinforce Foster + Partners’ observation that it is often owner-occupiers – of the likes of Willis Faber, the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Commerzbank and, in Pereira’s case, Transamerica – who can be relied upon to pioneer innovation, often setting new standards that will later be adopted by the market.

Lively then, lively now: reinstating the unique heritage of the site

Pereira and Foster + Partners met in print decades ago; today that relationship is far more tangible. Tasked by SHVO with renovating the Transamerica site, together the team endeavoured to recreate a neighbourhood that both acknowledged the rich history of the site and brought contemporary values and technology to it.

“Since it was first designed by William Pereira, the Transamerica Pyramid has been about the people and community it serves, from its generous design which allows light onto the street and redwoods below, to its bold form which serves as a tribute to San Francisco’s futuristic spirit,” said Michael Shvo, Chairman & CEO of SHVO. “Honouring this intent informs every aspect of the revitalization program we are carrying out in collaboration with Norman Foster and his team.”

Foster, Founder and Executive Chairman of Foster + Partners added: “With this reimagination, we will create a dynamic new neighbourhood within San Francisco that brings together elements that support the community’s wellness, sustainability and social fabric – in other words, returning the entire block to the traditional idea of a city. Our hope is to carry forward the spirit of William Pereira’s original vision as the Pyramid embarks on its next fifty years of looking to the future.”

The team has worked on the masterplan of the Transamerica site including The Pyramid itself (One Transamerica), 505 and 545 Sansome Street (Two and Three Transamerica, the former also designed by Pereira), and Redwood Park. Site-specific solutions were implemented to sustain a holistic balance between the cultural, architectural, and environmental elements across these buildings and the urban space between.

Inside the Transamerica Pyramid, for example, Foster + Partners’ design draws upon the building’s unique structural geometry and scale by carefully restoring the historic lobby. Decades of cladding were stripped away to reveal the original beams and cross-bracing beneath – a move which both reclaims valuable space and distils the essence of Pereira’s vision. An indoor-outdoor approach, suitable for San Francisco’s climate, was also adopted. The existing colonnade – made of triangular modules – was made visible inside the arrival area; a bridge has also been installed to re-connect the interior lobby with the Redwood Park outside. Through this restoration, users are brought closer to both Pereira’s design and the natural world.

The Foster + Partners team endeavoured to recreate a neighbourhood that both acknowledged the rich history of the site and brought contemporary values and technology to it.

The grand geometric scale of Pereira’s project appears at all stages of the design process. The interiors of the Sky Bar on L48, for example, incorporate pyramidal and triangular details in the edges of the counter, stools, and lighting fixtures. Materials have also been considered; quartz precast cladding and bronze metal comprise the building’s façade, both evoking and updating the 1970s detailing and harking back to the bohemian glamour of Coppa’s in Montgomery Block.

The Foster + Partners team endeavoured to recreate a neighbourhood that both acknowledged the rich history of the site and brought contemporary values and technology to it.

Outside, Foster + Partners paid close attention to the original plans for Redwood Park and, consequently, proposed an urban space that reconnected the separate buildings of Transamerica Pyramid Center. The overall strategy was based on three connected values: heritage, environmental conservation, and social interaction. Firstly, the landscape team brought back the original layout of the park as sketched by Pereira and his colleague, landscape architect Anthony Guzzardo – honouring the ground-level history of the site as much as the iconic pyramidal structure above.

Understanding both Pereira’s vision and the contemporary San Francisco climate, Redwood Park – with its famous redwood trees – was enhanced through the proposed planting of native vegetation. This increased the ecological diversity index of the habitat which will promote the ecological succession of local flora and fauna in the coming years. This has a wonderful effect on people, too. Not only does the park provide shade and naturally filtered air, but it creates valuable space for socialization, meditation, and re-connection with nature.

These sustainable, contextual and climate-responsive interventions combine to create a unique project that considers sustainability in truly holistic terms. People, place, and nature are carefully balanced; the vital relationship between the social and the ecological is reintroduced at the heart of San Francisco. Whether enjoying a Pisco Punch in the Sky Bar or having lunch in Redwood Park, users can access a deeper appreciation of the Transamerica site, feel emotionally attuned with their environment, and, consequently, with themselves and others.

Transamerica renewed

From the 1849 Gold Rush, through the century-long rise and fall of the bohemian Montgomery Block, to Pereira’s maverick pyramidal project in 1972: the Transamerica site has long been a witness to and a catalyst of San Francisco’s social and cultural history. Foster + Partners’ recent masterplan of Transamerica was, consequently, a challenging pitch; the team had to both honour and understand the history of the site and, somehow, continue to evolve that legacy. Their restorations in Redwood Park and numerous interior interventions achieve just this. Foster + Partners bring both historical sensitivity and technological and environmental innovation to this unique project and take part in San Francisco’s long-running ‘spirit and daring.’

Author

Irma Delmonte

Author Bio

Irma Delmonte is an architectural researcher at Foster + Partners. The research team explores a broad range of topics – across history, design, urbanism and cultural studies – to support designers in their understanding of site and context and collaborate in the development of complex research narratives. She obtained her BArch in Architecture and Conservation from University of Venice, where she worked on historical buildings of the city. She then gained her MA in Architectural History, Theory and Criticism from the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Editors

Tom Wright and Clare St George