The idea that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature is not a new one. However, its conscious consideration in the field of architecture and design is relatively recent. In the face of numerous studies that prove the benefits of embracing nature in our built environment, the design teams at Foster + Partners are elevating an intuitive inclusion of biophilic elements to the level of specific design choices with measurable benefits.

29th April 2020

Biophilia in Design

Natural instinct

The term biophilia stems from the Greek ‘bio’, meaning ‘life’, and ‘philia’, meaning ‘friendship and affinity’. Coined in 1964 by the social psychologist Erich Fromm and popularised by biologist, naturist and writer Edward O. Wilson during the 1980s, the word describes an innate tendency within humans to seek interactions and connections with the natural world.

Wilson’s research – put forward in his seminal text Biophilia, 1986 – declared that rapid industrialisation and mass urbanisation had led to a disconnect between humans and the natural world. This had negative effects not only on the health and wellbeing of people, but more importantly, on our neighbouring species; with this disconnect came a disregard for our habitat and the beings with which we share it. Wilson’s book was primarily a plea for a conservation of ethics and the preservation of animal species in all their diversity, but its message resonates well beyond the realm of environmentalism.

‘The empirical evidence for the beneficial impact of nature on human health is plentiful.’

The idea that humans have an innate connection with nature seems inevitable. For the first few hundred thousand years of our existence, we lived in the wild, continuously interacting with nature – to feed, wash, build shelter and more. It is only within the last 150 years or so that we have started to detach ourselves from it, and our DNA has yet to get the message. The empirical evidence for the beneficial impact of nature on human health is plentiful, and spans the cognitive, psychological and physiological systems. Regular connections with nature provide opportunities for cognitive restoration, increasing our capacity for learning, analysing and creating. Psychologically, natural environments can assist emotional restoration, lowering anxiety levels, reducing fatigue and improving overall mood. Physiological responses to nature include the relaxation of muscles, lowering of blood pressure and a reduction in stress hormones. You have only to think of the soothing sound of crashing waves, or the exhilaration of a windswept walk to recognise and appreciate such benefits.

As modern society and technology developed, humans came to replace nature as the architects of our own environment. In the context of shelter, this had undeniable benefits for life expectancy and general health. And yet, the resulting crowded, often-sterile nature of our modern habitat is in direct opposition to human design. We have evolved to live in an expansive natural environment, and our genetics cannot keep pace with the speed and scale of this change. The result is negative effects on our health and wellbeing; there is a startling correlation between the rise of mental health disorders in Western societies and their transformation from small agrarian communities to large urban metropolises. The World Health Organisation predicts that mental illness will be one of the largest contributors to disease in 2020.

‘In the 1990s, the green building movement paved the way for better designed, user-focused architecture.’

That our environment has a significant impact on our health and wellbeing is unsurprising, but an increased understanding of the specifics of this impact has revealed just how important a role our buildings can play in our thriving. In 1984, a landmark study by professor of architecture and landscape design Roger Ulrich provided definitive proof of the healing power of nature within the context of our built environment. In his study of surgery patients in a suburban Pennsylvania hospital between 1972 and 1981, the recovery rates of those assigned to a room with a window and a view of a natural setting were faster than those without. Not only that, their interactions with staff were more amiable, and their reliance on painkillers much less. And it is not just in a healthcare setting that biophilia can improve human performance. In the 1990s, the green building movement paved the way for better designed, user-focused workplace architecture. In 2017, researchers from Harvard’s Center for Health and the Global Environment published a study that saw the cognitive function of workers in green buildings (structures that in design, construction and operation are environmentally responsible and resource efficient) was markedly better than that of workers in a conventional building setting. On average, cognitive scores were 61 per cent higher in green building conditions. As the study suggests, such findings ‘have far ranging implications for worker productivity, student learning and safety.’

Over the last twenty years, more and more studies such as these have established a firm link between human health and productivity and the buildings and spaces in which we conduct our day-to-day lives. The connection is so clear that building standard certification bodies such as BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) now actively assess biophilic strategies in their awards process, and even better, new standards bodies – such as WELL Building Standard, established in 2016 – primarily ‘validate and measure features that support and advance human health and wellbeing’. As such, targeted biophilic design is now being championed as a strategy for combating workplace stress, improving student performance, assisting patient recovery, encouraging community cohesiveness and more.

Patterns in nature

It is estimated that by 2050, three-quarters of the world’s population will be living and working in cities. If we are to ensure the continued health and wellbeing of these communities, then it is essential that we incorporate biophilia into the design of our buildings. Natural themes in architecture – from internal courtyards and cottage gardens, to natural patterns and interior planting – have a long history. From the moment we stepped indoors, we have shown a desire to bring the outside in with us; consciously incorporating biophilia into the design of our structures and urban spaces is merely a calculated extension of this impulse.

In 2014, environmental designer and strategist Bill Browning and his colleagues at environmental consulting agency Terrapin Bright Green published a report which drew together years of research and analysis that defines the aspects of nature that most impact our satisfaction with the built environment. '14 Patterns of Biophilic Design' lays out a framework for designing spaces that optimise human health – be that at home, at work or in public spaces. These patterns are divided into three groups: nature in the space, nature of the space, and natural analogues.

Nature in the space ‘addresses the direct, physical and ephemeral presence of nature in a space or place’. This encompasses the presence of plants, water and animals, as well as notable sounds and scents. Nature can be mimicked in a space in various ways, through visual connections, aural stimuli, changes in air-flow and temperature, varying light conditions and more.

Nature of the space represents spatial configurations that occur in nature. We are designed to see beyond our immediate surroundings, often seeking the slightly dangerous, unknown or surprising. As designers of space, architects have unique control over these configurations, and can make obvious and deliberate choices that align with our unconscious needs.

Lastly, natural analogues refer to indirect evocations of nature that, although non-living, have a similar psychological and physiological effect on the brain. Materials, objects and shapes – be that furniture, artworks or textiles – can be chosen for specific characteristics and provide an indirect but no less meaningful connection with nature.

When simplified as such, incorporating biophilia into our building designs seems relatively straightforward. But as Browning and his team point out, good biophilic design draws on multiple perspectives – the surrounding natural environment, socio-cultural norms and traditions, the building’s function and resulting human rhythms and routines. If biophilic strategies are to be effective, they must successfully integrate with both people and place; identifying the users, location and purpose or operation of a space is key.

Work and wellbeing

Naturally, the healthcare sector has been at the centre of most study around the benefits of biophilic design. But one area of increasing interest is the workplace – biophilia impacts our health, and improved health (both mental and physical) results in enhanced performance. Foster + Partners has a long history in design for office and industry and many of our buildings have unconsciously incorporated the ingredients that Bill and his team have painstakingly identified and classified. In more recent years, this inclusion has moved from the implicit – elements that we have intuitively included in design – to the explicit – deliberate design choices that are based on an increasing understanding of the facts revealed through scientific and medical research.

Some of our earliest designs, such as the Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarters in Ipswich (1975), demonstrate an intuitive tendency towards design that mimics and incorporates natural structures. The biomorphic form of the building – itself a natural analogue – brings daylight deep into the building, with a visual connection to nature being made through the glimpse of sky. Elements of nature in space increase as one rises up within the building surrounded by internal planting, and higher levels reveal views on to the rooftop garden and surrounding landscape. The internal space is itself dominated by this progression from ground floor to roof, the escalators slowly revealing the mysteries of the space as you pass through it.

'We like, within reason, transient changes in our environment.'

More recently, we have developed a more quantifiable understanding of biophilic aspects of design, engaging them in a holistic vision for buildings. Research in these areas has included a close look at alliesthesia, a phenomenon that describes the change-seeking nature of the human body’s sensory and neural control systems. This essentially means we like, within reason, transient changes in our environments – not the static lighting, thermal and noise levels often specified for our buildings and enshrined in regulations and codes. A good example of effectively engaging alliesthesia is through natural ventilation, which can give a more natural and dynamic feel to a space and arouse the senses, improving cognitive function and productivity.

A system for effective natural ventilation was a key feature in our design for the European headquarters of the financial media company Bloomberg in the City of London (2017). A mixed-mode design, the building is capable of being either naturally or mechanically ventilated dependent on external conditions. Natural ventilation is introduced around the perimeter of the building from the second floor and above. Air inlets are either through the bronze fins, which form the building’s distinctive facade, or through stone walling elements near the lift shafts placed around the perimeter of the building. The air then exits the building through and around the atrium at level eight, the highest occupied floor. A variety of air quality monitoring stations are in place to ensure outside air is only admitted to the building when it is of acceptable quality. Thus far, the perception of natural ventilation has been positively received by the occupants.

'The Park was designed with a deep care towards both its staff and the environment.'

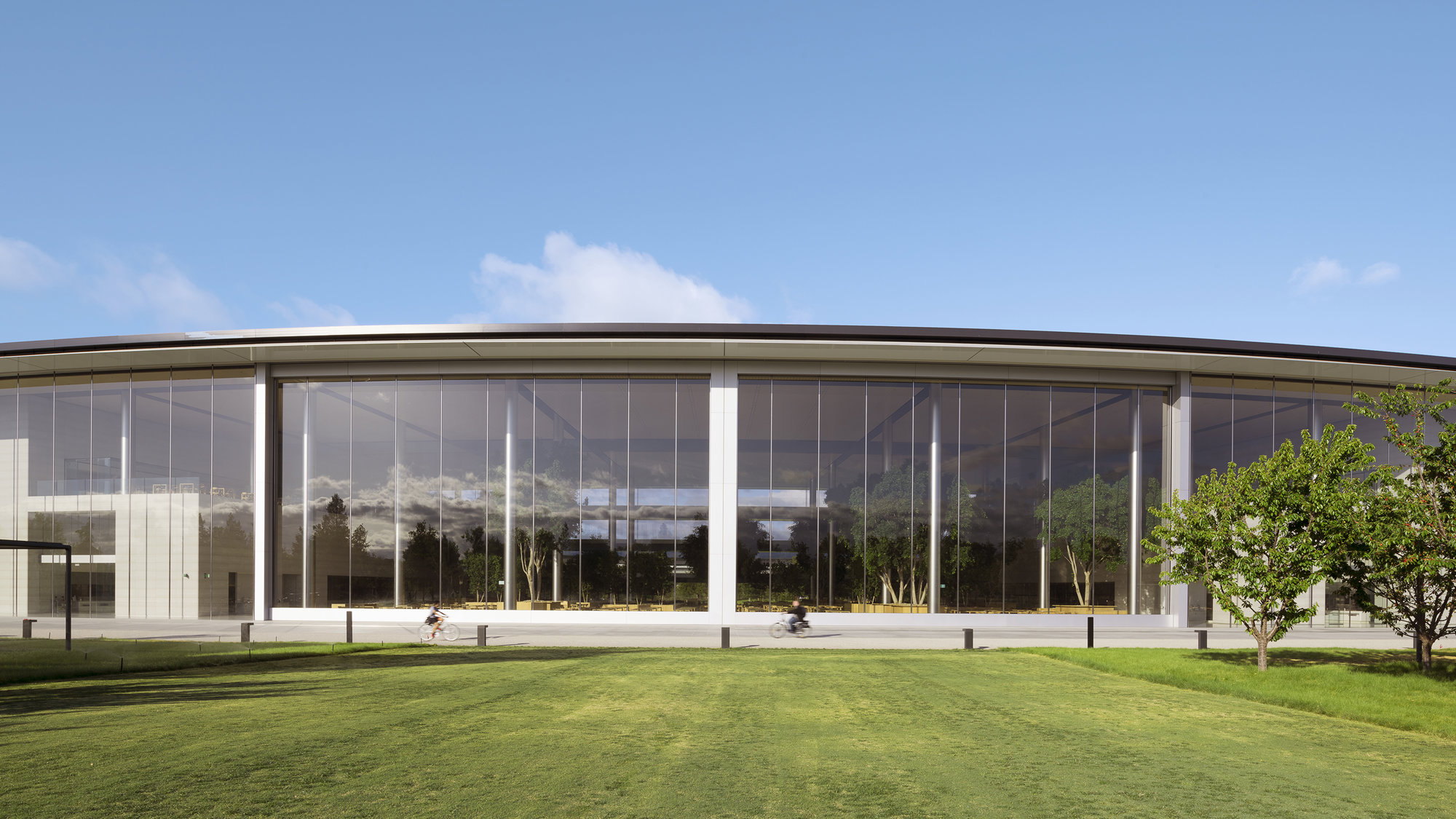

Features such as natural ventilation, radiant cooling systems, dynamic lighting capable of circadian programming with diffuse appearance, and ceiling systems with textured appearances – all which mimic conditions found in nature – are now consistently incorporated into our designs for corporate clients. A recent, successful example of some of these strategies can be seen at Apple Park in Cupertino, California (2018). An exemplar of sustainable design, the Apple campus is powered by 100 per cent renewable energy, and is on track to be the largest LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Platinum-certified building in North America. Importantly, Apple realised the importance of employee health and wellbeing in its success as a company, and the Park was subsequently designed with a deep care towards both its staff and the environment.

In terms of the ’14 Patterns’, Apple Park delivers on several levels – particularly regarding nature of the space. Its landscape and buildings form a seamless whole; the architecture is surrounded by parkland (the green space of the original site has increased from 20 to 80 per cent), sitting low amid tall trees and allowing invigorating views through its glass facades. In the Ring Building, full-height (four-storey) atria create light-filled entrance commons that connect the park outside to a large garden space within. These direct connections to nature, and natural light rhythms, are complemented by interior strategies including natural ventilation. Like Bloomberg, the Ring Building operates a mixed-mode strategy, relying on natural ventilation when and where possible, alongside integrating radiant cooling with the concrete ceiling. The system is intelligent enough to consider seasonal rhythms, creating a connection with nature and minimising what scientists call ‘thermal boredom’.

Nature is nurture

In the context of the workplace, biophilic design features are not only beneficial, but as the designs here demonstrate, increasingly achievable. And as more and more studies make the link between nature, health and wellbeing, and human performance, more and more businesses are recognising the importance of incorporating such strategies into their working environments. Importantly, the implementation of these features has revealed the larger potential of biophilia in design – one that transcends boundaries of typology to encompass not only healthcare and industry, but also education, culture, residencies, civic properties and urban masterplans.

Our dedication to sustainable, holistic design that is respectful of both people and the environment has led to designs that naturally complement a biophilic programme; at Sulis Hospital Bath (formerly Circle Hospital Bath) (2009), a health centre in the UK, a central double-height atrium draws in natural light through circular skylights. The interior colour palette is a warm and friendly mix of ochre and rust, with natural wood acoustic panels above, interspersed with glass panels that provide a visual connection to the atrium from the bedrooms arranged around it above. At the South Beach complex in Singapore (2016), a wide landscaped pedestrian avenue – a green spine – weaves through the site and is protected by a large canopy, which captures prevailing winds and directs air flow to cool the ground level spaces. The highly permeable pedestrian realm provides comfort and shelter for busy workers and residents.

As the designs profiled here age and evolve, further evidence of the benefits of biophilia in architectural design are sure to emerge. In the meantime, we are committed to restoring the instinctive human-nature connection in the built environment wherever possible, so that we might live healthier, more sustainable and more considerate lives.

Author

Chris Trott

Author Bio

Partner Chris Trott is a Sustainability Engineer within the Sustainability Group at Foster + Partners; working directly with the design teams, the group delivers insight, informs direction and measures improvements to develop a sustainable vision for projects carried out by the practice.

Editors

Tom Wright and Anna Watson