For centuries, the library has mediated knowledge by providing space for its storage, retrieval, and exchange. How can this mediative nature be discussed in architectural terms? And how, given the dramatic shifts in our production, consumption, and attitude towards knowledge, might the library be evaluated today?

28th August 2023

Architectures of Knowledge: Designing the Library

Boundary conditions: What should a library be?

Foster + Partner’s House of Wisdom in Sharjah, UAE, was completed in 2021, as global restrictions on movement were beginning to ease. This new ‘House’, a community library formulated as part of a UNESCO World Book Capital initiative, coincidentally offered an alternative to the mental confinement in the ‘home’ brought about by the pandemic. The completion was timely; it testified to a sustained – perhaps even growing – need for flexible spaces where people could learn and commune. It asked how knowledge is conceptualised, accessed, and shared in a built environment. And it (re)imagined the library in its contemporary context as a space not just for books, but for people.

Described by architect and writer Michael Spens as the ultimate ‘repository for social values,’ the library is a key interface, a contact point, between an individual and their broader social and cultural field. This fundamental condition of the library as the border space between worlds – real, instructive, or imaginary – has manifold spatial consequences. As social historian Ken Worpole comments:

Libraries operate on the boundary between the secular and the sacred, between the archival and the exploratory, and between upholding the irreplaceable tradition of the book whilst embracing new media and technology…. The library has to imbue all its spaces both with a sense of pluralism as well as universality.

In accommodating these various oppositions (one might add conservation/interaction, focused research/chance encounter, materiality/ephemerality to Worpole’s list), the library must provide both a wide range and a specificity of experience for its users. It has, as a result, become an architectural form that is acutely aware of its own function as a mediative space; it is always, like the very act of reading that it facilitates, on a ‘boundary between.’

Claims made for a library’s mediative spatiality, though relevant to a broader discussion of how knowledge is encountered, risk abandoning the library building itself. A space characterised by liminality is still designed, built, and used; discourse surrounding the concept of the library should not eclipse the more practical questions of accessibility and navigability (not to mention funding) that are essential to its daily functioning. Altogether, the library architect must produce a coherent, legible space that considers a library’s specific collection and the community that it serves. So how, given these philosophical and practical concerns, can we discuss and evaluate these architectures of knowledge?

A history of the library is a history of knowledge

‘Long considered primarily as repositories for books and periodicals, the role of libraries in the life of contemporary communities has changed dramatically,’ observes Senior Executive Partner and Head of Studio, Gerard Evenden. And yet ‘the idea of a library of the future is inextricably linked with spaces that allow people to gather, learn and exchange ideas.’ These are timeless architectural ideals that go back to our most foundational civic, cultural, and educational edifices.

Haeinsa Temple, Hapcheon County, South Korea was built in 802 AD. Haeinsa is most notable for being the home of the Tripitaka Koreana, the whole of the Buddhist Scriptures carved onto 81,350 wooden printing blocks, which it has housed since 1398 AD. © CC BY 2.0

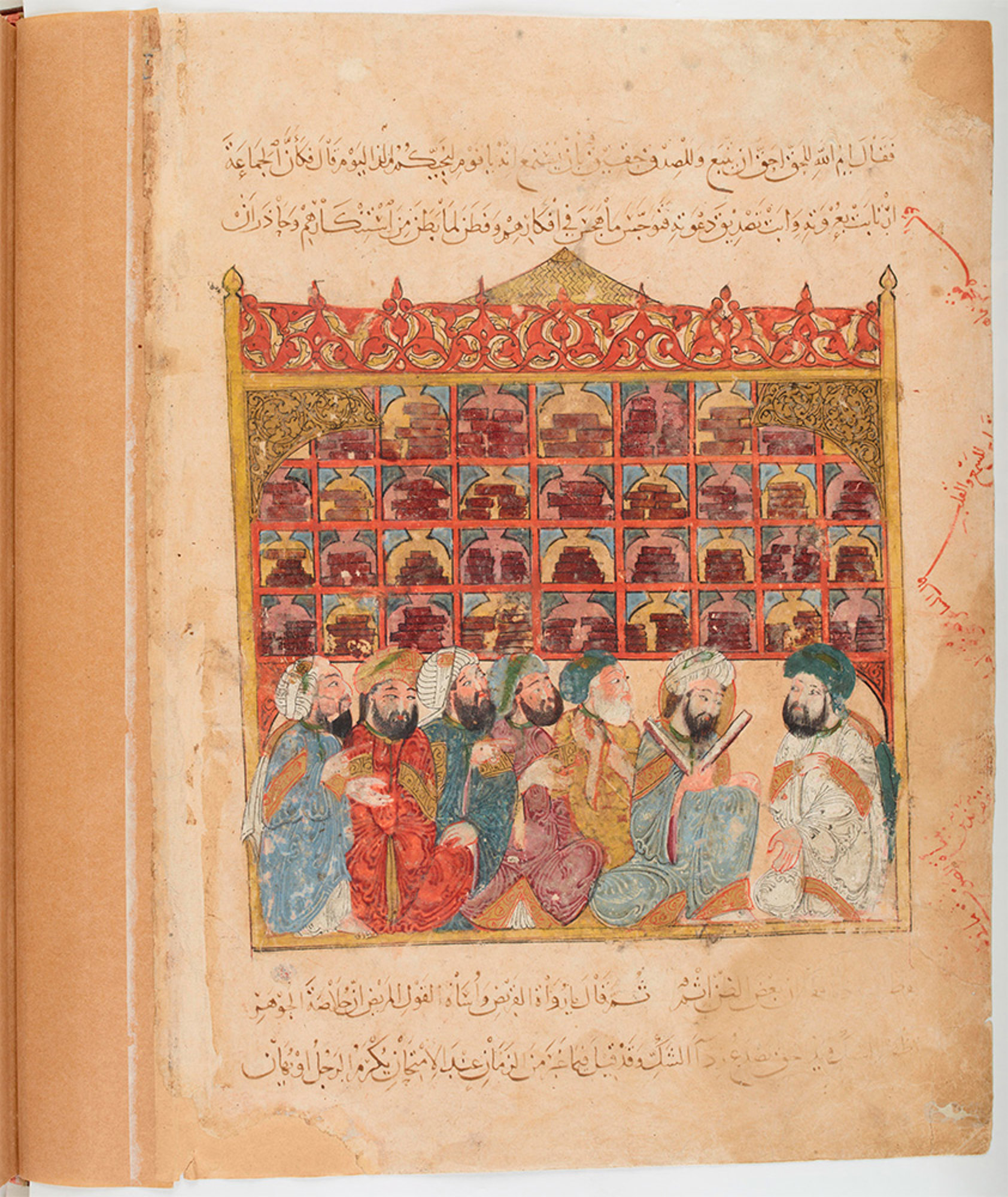

Scholars at an Abbasid library, perhaps the Grand Library of Baghdad in the Maqamat of al-Hariri. Illustration by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, c. 1237. ‘The Assemblies of al-Hariri’ manuscript courtesy of the World Digital Library.

What we understand as ancient libraries – the Greeks’ mythologised Great Library of Alexandria, the Assyrian Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, or Roman Emperor Trajan’s Bibliotheca Ulpia – were part of a world in which there might only be one copy of an authoritative religious or scientific inscription, where information was singular and slow in comparison to its abundance and immediacy today. For centuries, the library tended to be a private and elite institution, reserved only for those with high levels of social, religious, or academic access. Scholars would undertake extensive tours to study and commune with their peers in these sanctified spaces. Across the globe, different iterations of the library space communicated a deep appreciation of and commitment to the preservation of knowledge.

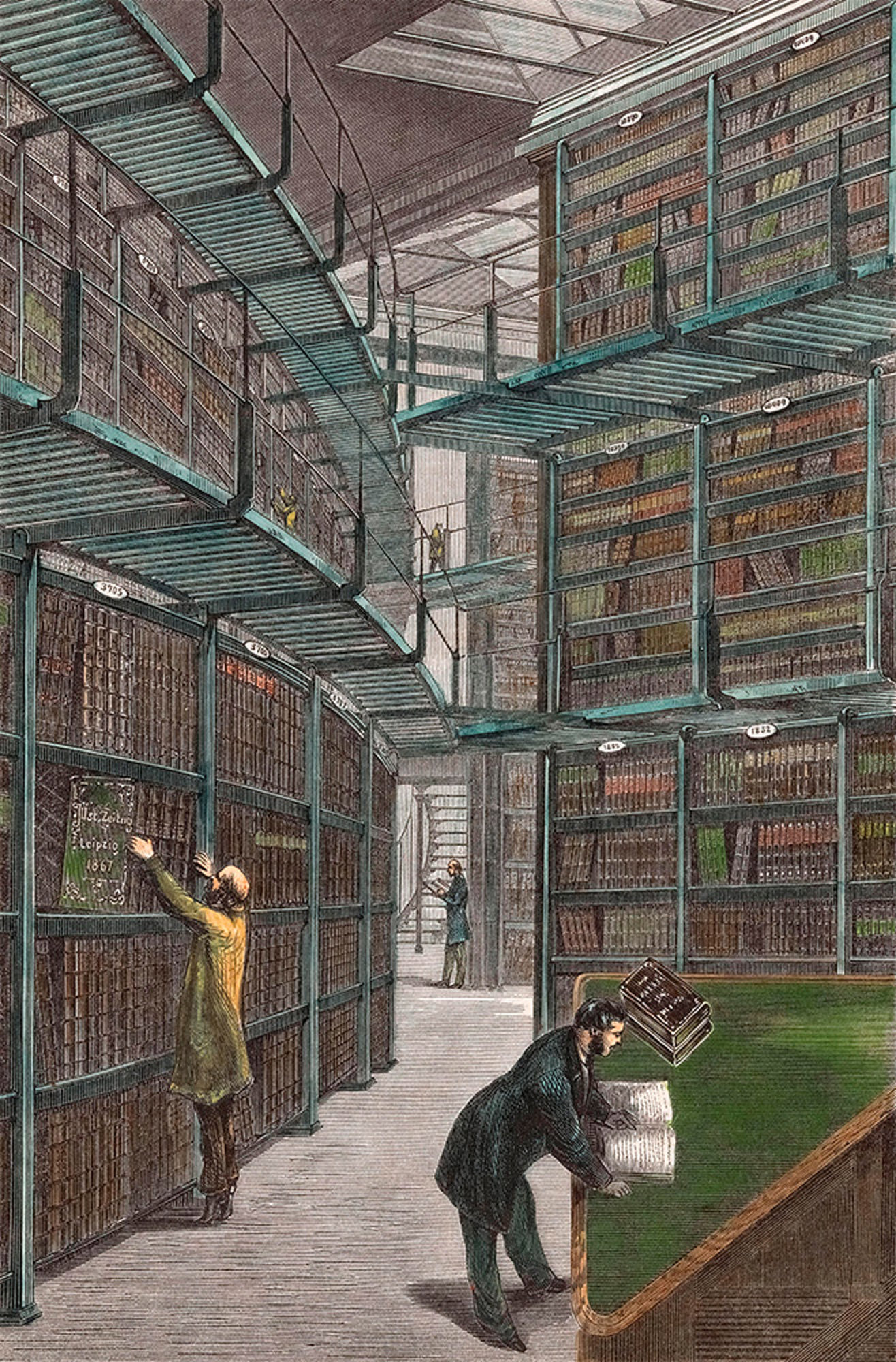

Millenia later, the invention of the printing press and developments in translation practice as a part of Renaissance scholarship meant a great expansion and dissemination of texts. Collections – and the grand buildings that housed them – were ways to indicate status and influence. Still, lending was not encouraged to a wider public; books were often chained to shelves and, if outsiders were admitted, reading was closely supervised.

Biblioteca Malatestiana. Purpose-built from 1447 to 1452 and opened in 1454, and named after the local aristocrat Malatesta Novello, is significant for being the first civic library in Europe, belonging to the commune (rather than the church or a noble family) and open to the general public. The library was inscribed in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2005. Photograph courtesy of Lauren Heckler © CC BY-SA 4.0

Within a European context, the broadly private nature of library architecture began to shift in the eighteenth century, where popular Enlightenment philosophy emphasized the importance of learning and acquiring knowledge as essential to collective civic life. Libraries were becoming increasingly public and were more frequently established as lending libraries. In the United Kingdom, the Public Libraries Act of 1850 gave local boroughs the power to establish free public libraries for the first time. This was a key moment in the development of literacy levels in the population and was followed by legislation for compulsory education in 1870; in 1800, 60 per cent of men and 40 per cent of women were literate, but within a century the number had soared to 97 per cent for both sexes.

Discourse surrounding the concept of the library should not eclipse the more practical questions of accessibility and navigability (not to mention funding) that are essential to its daily functioning.

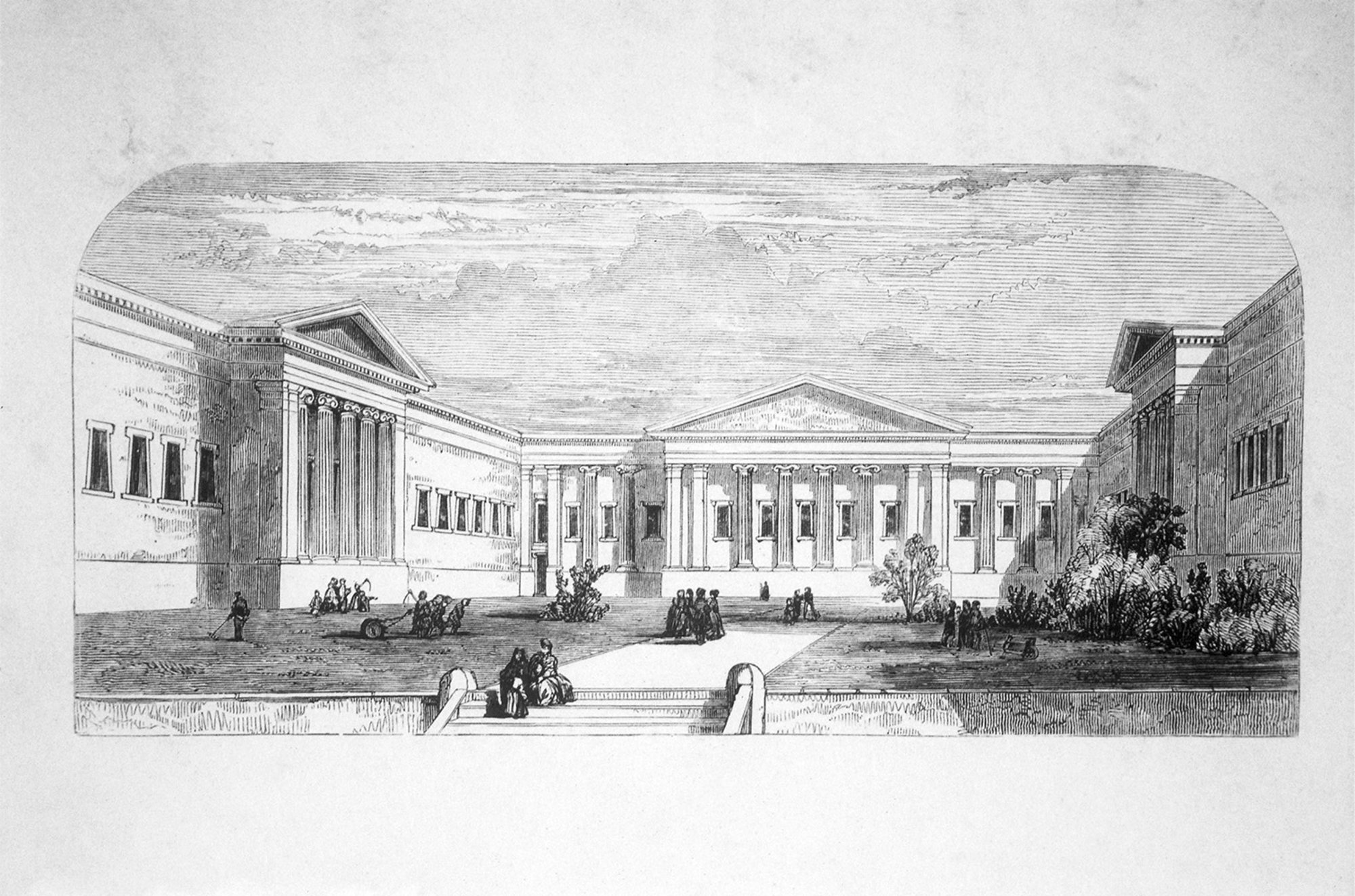

In the centuries preceding Norman Foster’s founding of Foster + Partners, then Foster Associates, the role of the library had undergone a shift predicated on the gradual sharing of knowledge to the public and the dramatic increase (and lowered cost) of publications. This transition can be followed within the British Museum, for example, and its library collection’s relationship with the changing architecture of the site. The British Museum Library was founded in 1753 and housed 50,000 books. Despite this scale, the library was not open to the public, or even to a majority of the population; instead, access depended on passes, of which there was sometimes a waiting period of three to four weeks. Sydney Smirke’s Reading Room, added in 1857, was a key attempt to foreground the collection. However, it remained inaccessible to the public and soon became untenable given the rapid growth in library acquisitions and museum-goers.

The inner courtyard of the Museum before the Round Reading Room was built. Image courtesy of The British Museum.

The collection was moved in 1997 to the purpose-built British Library in Kings Cross to be properly stored and managed. Smirke’s Reading Room was restored by Foster + Partners in 2000 and was made available to all Museum visitors for the first time. It remained, for some time, a ‘modern information centre’ housing ‘a collection of 25,000 books, catalogues and other printed material, which focused on the world cultures represented in the Museum.’ Today, that function is in flux as the Room is used for the Museum’s archive but is accessible only via pre-booked visitor tours.

The most notable element of this restoration, however, was Foster + Partners’ addition of the famous Great Court roof. Created using innovative parametric design tools, the roof shelters yet lightens the formerly inaccessible courtyard and encourages circulation within the atrium for a global museum-going public. As Norman Foster has observed:

If architecture is about the creation of spaces then light is the medium that models and brings these spaces to life. There is a poetic dimension to the constantly changing qualities of daylight.

Foster + Partners’ vision meant that the original inner courtyard could be seen again, for the first time since 1857 when the Round Reading Room was completed. The Great Court was opened in December 2000 by HM The Queen, the largest public covered square in Europe. The Reading Room remained a library and resource centre, with books focused on the Museum's collection and history. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Alongside the British Museum, the following projects – some libraries, some featuring libraries, some behaving like libraries – explore how architectural design is in dialogue with changing structures and scales of knowledge. The Free University Library (2004), the Carré d’Art (1993), the House of Wisdom (2021), and Narbo Via (2019) all look for ways to curate and make legible our cultural values as recorded and recalled in text. They mediate across our permeable boundaries of past and present and, in doing so, offer glimpses into the future and how architectures of knowledge might adapt to a rapidly accelerating digital era.

Free University: The academic library

This modern emphasis on libraries as places of equitable learning was adeptly expressed in Foster + Partners’ Philological Library for the Free University in Berlin. Following the war, the foundation of the Free University in 1945 marked the rebirth of liberal education in the city. Like the Great Court at the British Museum, the Free University Library uses light – alongside circulatory floors plans and well-placed shelving – to counter the tired association of libraries as unnavigable and isolating.

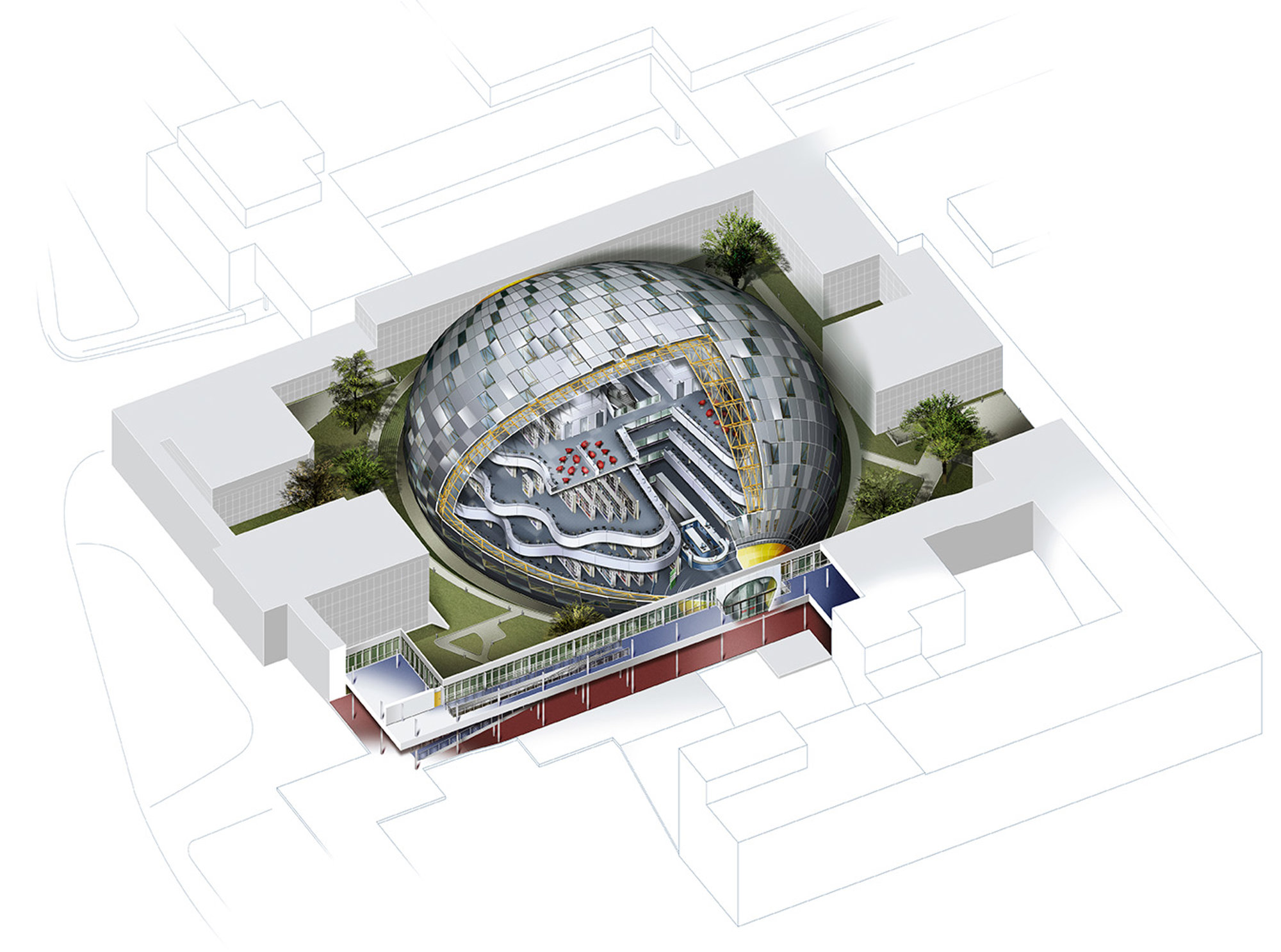

The library’s four floors are contained within a naturally ventilated, bubble-like enclosure, which is clad in aluminium and glazed panels and supported on a tubular steel frame with a radial geometry. A translucent inner membrane filters daylight, while occasional transparent openings allow glimpses of sunlight. The bookstacks are located at the centre of each floor, with reading desks arranged around the perimeter – a decision that not only encourages the circulation of people but allows a maximum amount of natural light to enter the building. As well as providing a ‘poetic dimension’ to the space and alleviating a dullness historically associated with academia, natural light has been proven to aid concentration and wellbeing, making it an appropriate architectural feature for a place of research and study.

Even the serpentine profile of the Free University Library’s floors has a ‘lightening’ effect; they create a pattern in which each floor swells or recedes with respect to the one above or below it, generating a sequence of generous, light-filled spaces in which to work. The library’s cranial form, as seen from outside, has earned it the nickname, ‘The Berlin Brain’ – a title that epitomises the relationship between its architectural form and academic function.

The architectural use of daylight and of circulatory patterns within a library is both a practical and philosophical answer to questions of modern, accessible academic practice. Like Foster + Partners’ refurbishment of the Reichstag (1999) in Berlin – a simultaneous project which sought to reflect a renewed national identity for Germany – the emphasis on transparency and equitability at the Free University celebrates forms of knowledge that are connected, democratic, and open to expansion.

Carre d’Art: The multimedia library

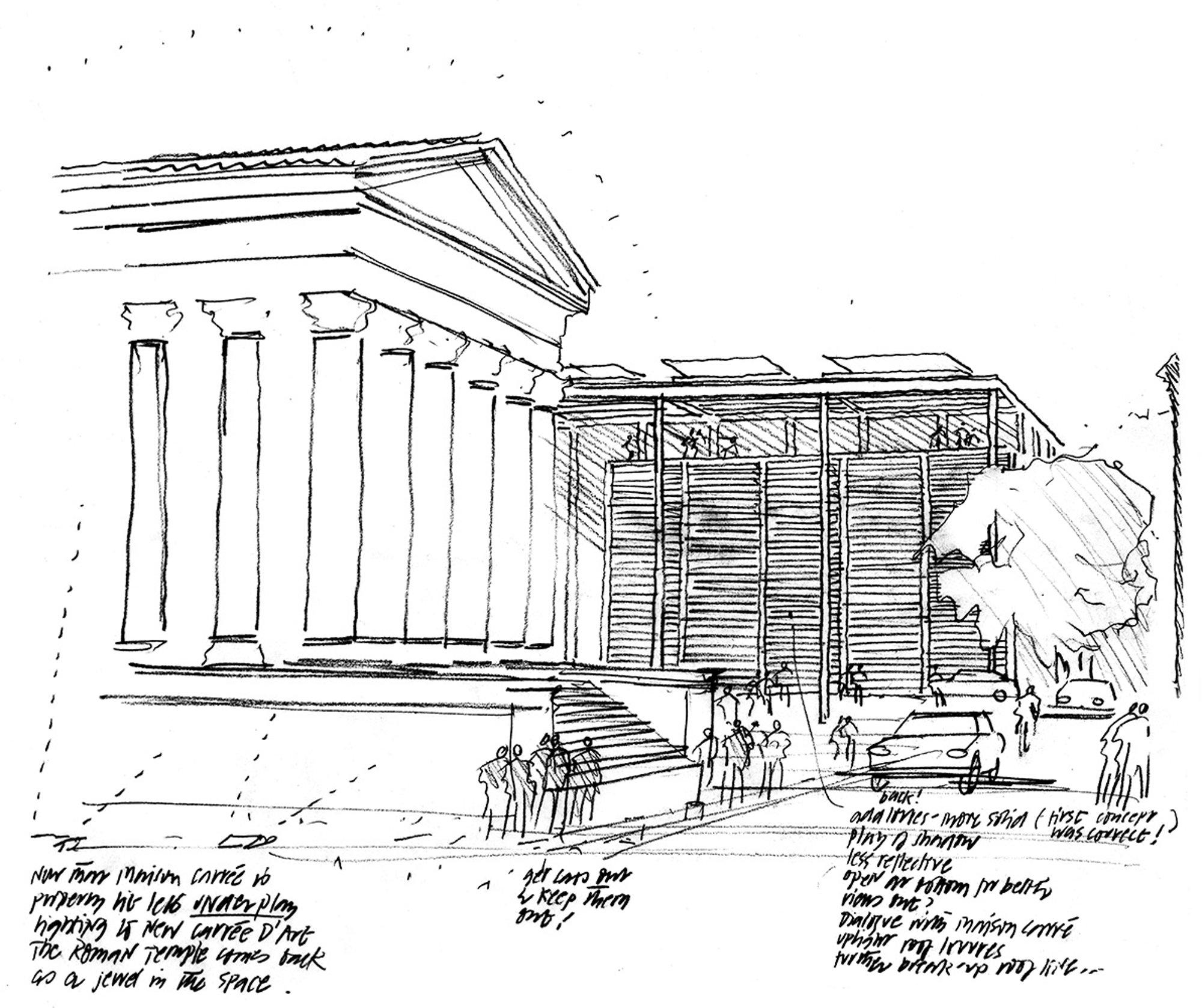

Foster + Partners also understood the modern library as a form where different types of knowledge could be curated and accessed by a range of people. The Carré d’Art, for example, was designed to provide a médiathèque (films, music, magazines, information technology, and books library) for the community of Nîmes, France.

The scope of the project was extended by the presence of the Maison Carrée, a Roman temple (c. 16 BC) next to the building’s site. Foster + Partners proposed that the Maison should be respected as a social focus of the square and suggested lowering much of the Carré d’Art below ground to better relate to the height of the existing temple. Appropriately, this contextual connection with ancient Rome is mirrored in the varied programme of the médiathèque – the first Roman public library, established by Caesar’s lieutenant Asinius Pollio in the first century BC, was a multi-purpose building, containing both an art gallery, archive, offices and a scroll library.

The library is acutely aware of its own function as a mediative space; it is always, like the very act of reading that it facilitates, on a ‘boundary between.’

As with the Free University, this involved a consideration of natural light in the Carré d’Art. With much of the building underground, its lighting was considerably more variable. As Norman Foster commented on the design process:

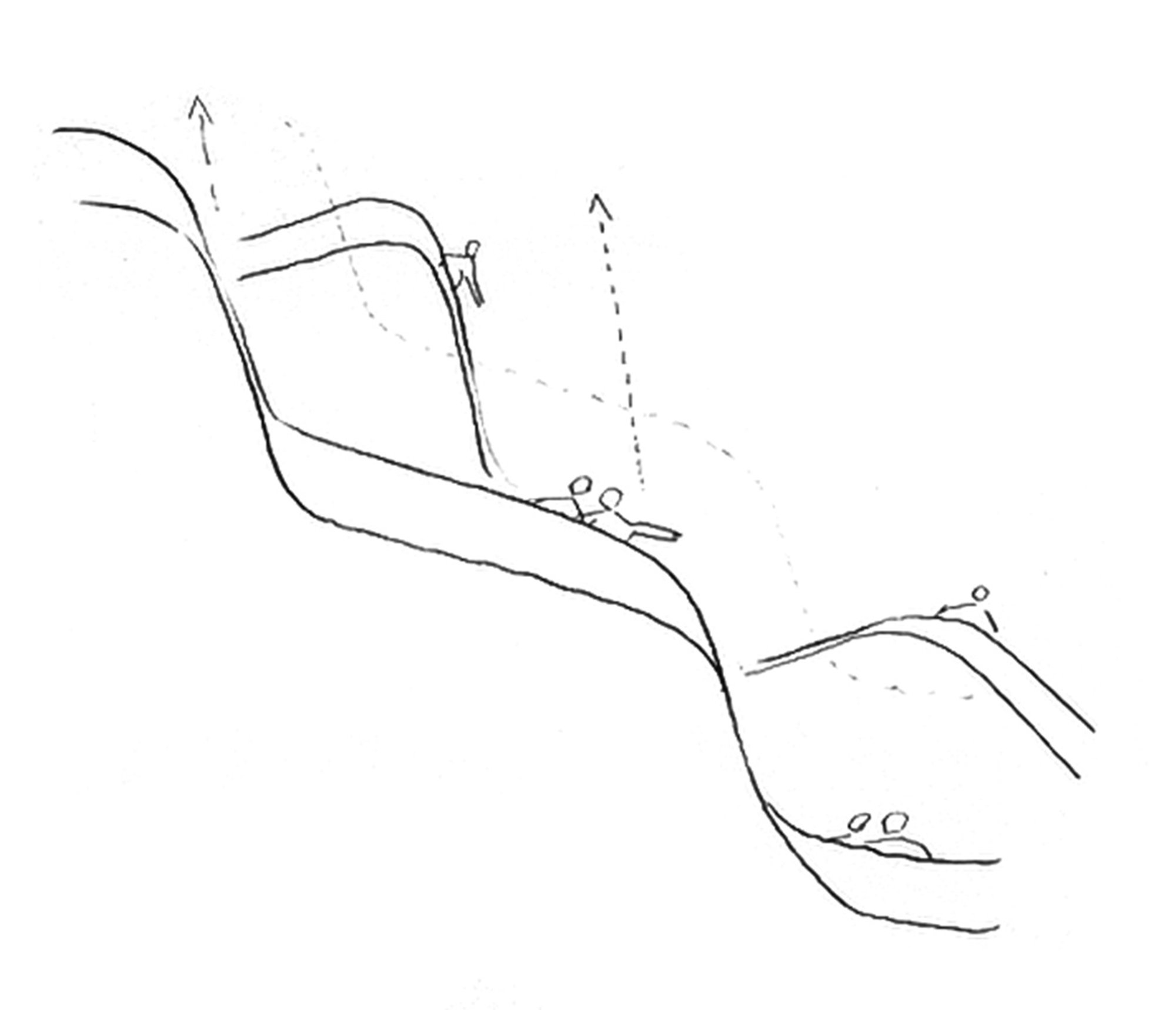

Thinking back, two themes keep recurring: the culture of the place – the city and the surrounding landscape – and the impression of a particular light. I recall emerging from the dark tunnel of trees which line the Boulevard Victor Hugo into the Place de la Comedies to be dazzled by the explosion of light. The site itself brings these two themes together.

The project’s sensitivity to variable light is part of its architectural negotiation of a cultural landscape of Nîmes which, in turn, finds its way into the layout of the building. The lower levels house archive storage and a cinema. Above, two library floors and art galleries on the upper two levels exploit the transparency and lightness of modern materials and bring daylight inside. A reception space on the uppermost floor opens out to a shaded café terrace overlooking a revitalised public square. By allocating media to different levels and different lightings, the building does a certain amount of editing and clarifying for its users.

In 2017, a quarter of a century after the Carré d’Art first opened, Foster + Partners worked with the client, Ville de Nîmes, and a local architect, Luca Lotti, to modernise elements of the building to respond to changing needs and user demands. Interventions included: developing new layouts in response to the way today’s users prefer to work, listen to audio, access materials online, relax, study and interact. New support for digital displays, photography, books and three-dimensional exhibits was incorporated, as well as a rotating preview of the library's collections and new acquisitions near the press kiosk. Wherever possible, the building’s original and distinctive features were maintained aiming for as a sustainable an upgrade as possible.

Inside the Carré d’Art atrium after its refurbishment. Rising six storeys through the heart of the building, the atrium links all the main public areas to create a natural thoroughfare bustling with activity at all hours of the day. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

The Carré d’Art demonstrates how a sensitive approach to context can produce a building that performs as a cultural microcosm of its surrounding environment and the people who use it. What’s more, its recent refurbishment is an example of a library successfully adapting to and embracing shifts in these contexts. In a century where the library has been under extreme pressure to justify itself, the Carré d’Art is an important example of how libraries can continue to provide for their users through sustainable, flexible, and sensitive architectural planning.

House of Wisdom: The community library

The sensitivity with which Foster + Partners designed the Carré d’Art can be felt in another community-oriented project, The House of Wisdom (Sharjah, UAE). Celebrating the naming of Sharjah as the 2019 UNESCO World Book Capital, the House of Wisdom is designed to be a social hub and centre for learning for its residents, and a statement on the continued importance of libraries as spaces to acquire, share, and store knowledge. John Blythe, Senior Partner and architect at Foster + Partners, reflected:

We wanted to put in a piece of everything, everywhere. Different zones for reading, research, study, socialising, and children. The project was designed to be as flexible as possible, including a gallery, auditorium, and dedicated study spaces which could move between an individual and a collective feel. The House of Wisdom team understood the library as a kind of organism; it has distinct parts that meet different needs which, together, ensure its diversity and success.

Foster + Partners designed a library that is as fully integrated and adaptable as possible, but which also provides specific experiences for its users. Prayer spaces with adjacent shoe storage, baby-friendly areas, and a mixture of public and private reading rooms all meets the needs of the Sharjah residents and students from nearby universities. This is a project that understands knowledge as diverse, diffuse, and multiform – and that different people access it in different ways. A successful library must be able to facilitate this and provide a mediative space where these various activities and impressions can occur.

Perforated aluminium sunscreens comprise the facade, providing shading and cooling. The facade design was influenced by traditional barasti architecture – a vernacular identifiable by its woven wooden screens that keep buildings cool and shaded in the Arabian desert sun. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

Foster + Partners used parametric design tools to create accurate visualisations of how light reacted and passed through the perforated panels, allowing designers to test different angles and positions. © Chris Goldstraw

The Scroll, by Gerry Judah, at the entrance to the library, offers a contemporary interpretation of ancient Arabic scrolls through its spiralling outline that loops towards the sky. It celebrates reading and the power of language to unite and to edify, central to the purpose of the House of Wisdom and that of the UNESCO World Book Capital initiative. © Nigel Young / Foster + Partners

David Nelson, Senior Executive Partner and Co-Head of Design at Foster + Partners, adds:

There’s a real magic to the House of Wisdom. It’s welcoming, calming, it puts people at ease. Even the light, as it splits through the shades and playfully punctuates the interior, has a richness to it. It seems to me that the building is an open-ended resource that can evolve with its community. This is essential when designing a space where people feel they truly belong – now, and in the future.

Narbo Via: The (re)collective library

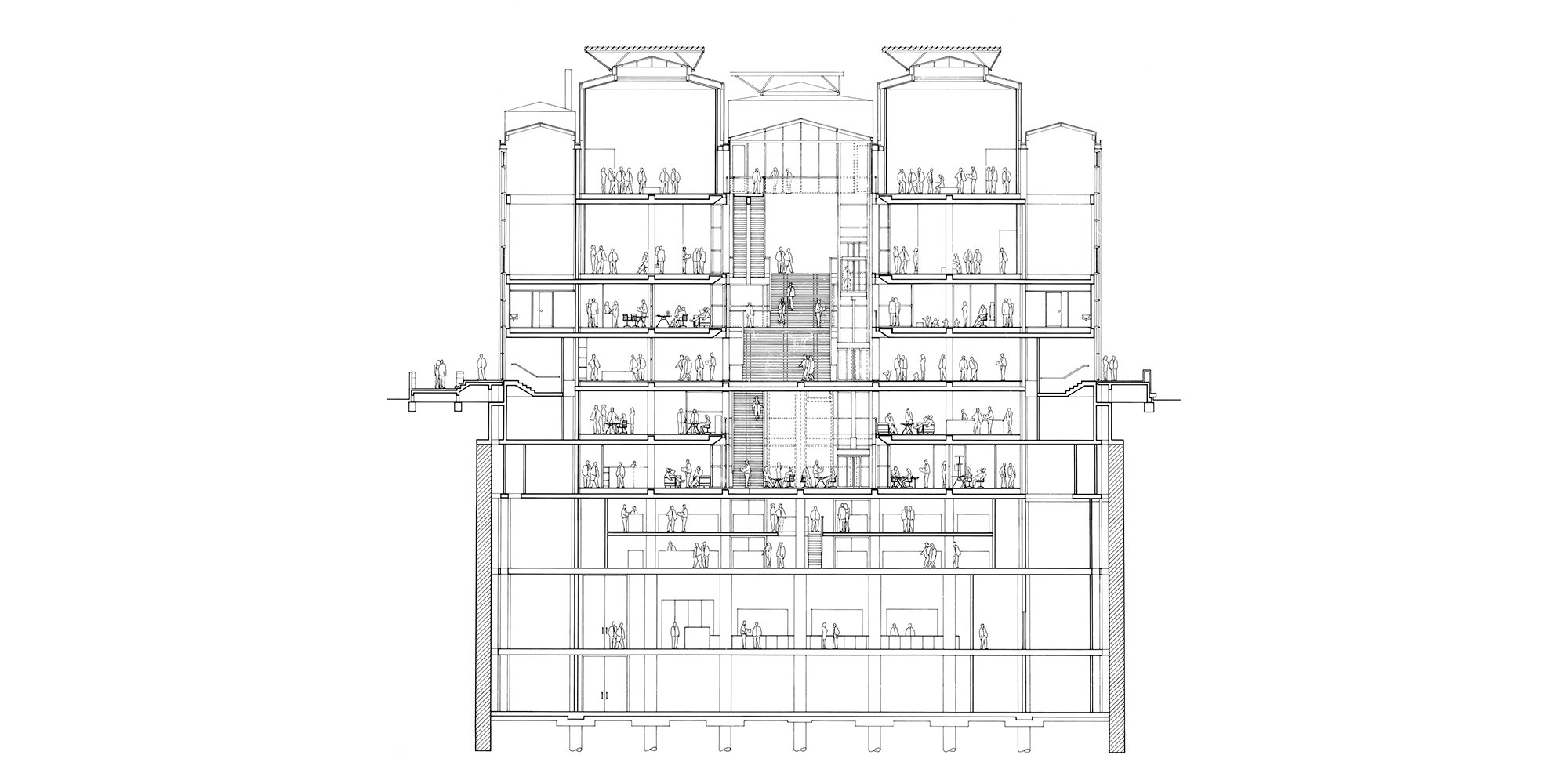

The three previous examples all anticipate a future expansion or change to their collections. But what happens when the collection housed is finite? Such was the case in Narbo Via (Narbonne, France, 2019), an ambitious museum project – including gallery spaces, a multimedia education centre, auditorium, and research facilities – dedicated to the Roman history of the Narbonne area, a once-major port during the Empire. Though not directly a library, Narbo Via’s archival ‘Lapidary Wall’, which stores and displays a series of Roman funerial stones in flexible shelving, makes visible the practice of mediation implicit in the library form. Over seven metres high and running the 70-metre-width of the building, the Wall was made by an integrated team at Foster + Partners, in collaboration with the museographer Adrien Gardère.

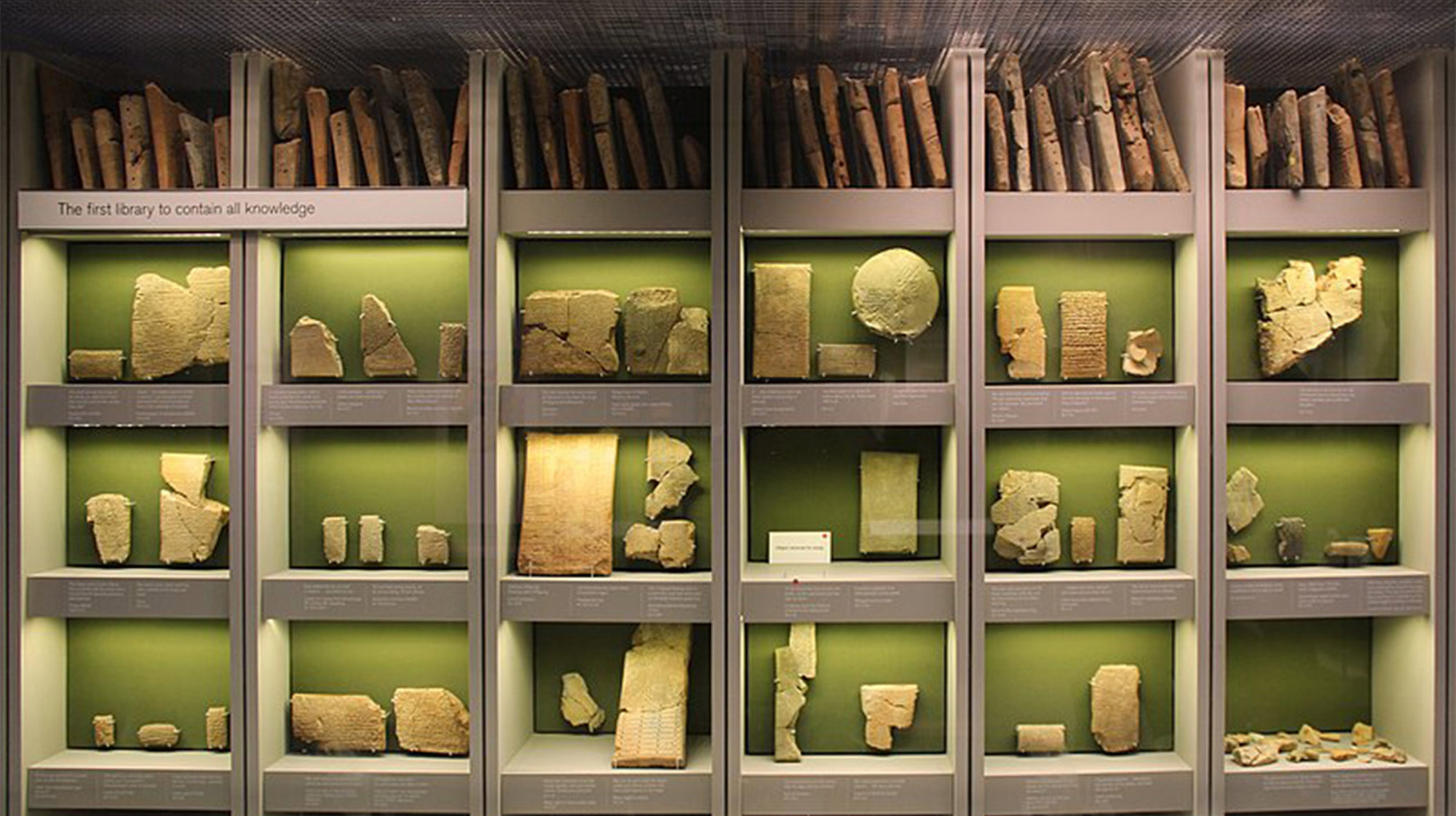

Narbo Via is both public and private space, a laboratory for exhibition and conservation; Roman libraries were similarly multifunctional spaces, offering facilities to the public, praetors, and prefects of the city. Acting as a permeable barrier at the heart of the museum, the Lapidary Wall functionally separates the public galleries from the more private research spaces while maintaining the possibility for exchange. Through the Wall’s mosaic of stone and light, visitors can glimpse the work of the archaeologists and researchers. They can also interact with the Wall. It’s open framework, served by a stacker crane, allows the artefacts to be retrieved and displayed alongside interactive screen panels in new configurations. This is not unlike the process of searching for a book – or perhaps even the digital equivalent of retrieving a file.

Narbo Via does not simply ‘keep’ memory but encourages the present-day act of remembering.

This practice of (re)collection is a key tenet of a library’s function. As Ken Worpole, once again, notes: ‘Library buildings are frequently held to be sacrosanct or precious, because of [their] memory-keeping role.’ The team understood and extended this by bringing Narbo Via’s objects into new and productive conversations with the building’s users. The museum does not simply ‘keep’ memory but encourages the present-day act of remembering. Spencer de Grey, Senior Executive Partner and Co-Head of Design at Foster + Partners, discusses the core principle of Narbo Via:

Our approach has been to create a simple yet flexible architectural language, one imbued with a sense of monumentality and links to history and culture – essential for this museum of 'living' antiquity.

This ‘simple yet flexible’ architectural approach can be felt throughout the building, where historical designs are referenced and blended with technology. The axial planning of Narbo Via’s spaces and courtyards is evocative of Roman villas and the loadbearing walls, sitting over a raised floor, allow mechanical systems to circulate heat and air – not unlike the engineering of a Roman hypocaust. These coloured concrete walls, made from layers of dry-mixed concrete tamped into place on-site are the first instance of Sirewall (Structural Insulated Rammed Earth) in France. Their stratification of colours, derived from local aggregates, calls to mind not only the archaeological nature of the museum but also the appearance of Roman concrete.

A union of antiquity and technology, Narbo Via is a project that encourages its visitors to access and participate in a shared cultural inheritance, as Gardère explains:

This ‘glyptotheque’ or monumental stone ‘library’ is constantly rearranged thanks to proven modern techniques used in automated industrial shelving…. This creates new ways of looking at the stone blocks in relation to one another … it holds up objects to be seen, admired and understood, but it also allows us to share, contextualise and study this unique collection using contemporary imaging tools and augmented reality.

This temporal approach is an essential aspect of Narbo Via's design, as de Grey adds:

The display of these ancient stones is a visual metaphor of Narbo Via’s mission statement; it is an impressive revelation to be admired and enjoyed by all, an active tool for learning, rather than a passive display. We were against the idea of providing publicly inaccessible off-site storage that would house the majority of the artefacts the majority of the time. Instead, we designed the Lapidary Wall to function as both storage and display for the entire collection. Every stone is accessible and each can be taken down for research and rearranged to inspire original interpretations – connecting the past with the present and future.

By designing according to a (re)collective practice that considers how historical structures and resources can be (re)presented, Narbo Via is an architecture of knowledge that stresses the importance of movement between past and present. Though not a library in the strictest sense, the Lapidary Wall’s innovative and effective use of the shelving and automated collection offers vital lessons for library design today. It asks us to consider how we should store, call upon, and read a shared history.

Future Architectures of Knowledge

There is a remarkable double-meaning at work in the Lapidary Wall of Narbo Via: that of the tablet. By displaying Roman stone tablets next to digital tablets (of similar proportion), ancient and contemporary forms of knowledge are brought into conversation. Alongside one another, they reveal visual and tactile affinities between past and present versions of reading and inscribing.

This approach seems apt when, as public art curator Huib Haye Van Der Werf comments in The Architecture of Knowledge: ‘We live in an age in which knowledge and communication are profuse. More important perhaps are the blurred boundaries between the producers and consumers of information within this development.’ Narbo Via uses the visually porous Lapidary Wall to connect ‘producers and consumers’ – in this case, the visitor with the real-time work of the archaeologists, researchers, and conservationists. It is an architectural record of how our orientation towards knowledge has changed – as has the way that we store and retrieve it.

By displaying Roman stone tablets next to digital tablets (of similar proportion), ancient and contemporary forms of knowledge are brought into conversation.

Architecture might address this change through a combination of analogue and digital design strategies. Saina Akhond, a Design Systems Analyst and robotics expert working within the practice’s Specialist Modelling Group, is considering a range of questions concerning twenty-first century library architecture.

I have noticed many parallels between the shelving systems of traditional libraries and our current data centres; the two seem to speak to one-another in quite an uncanny way. Within my work at Foster + Partners, I’m exploring ways that libraries can respond to the rapid development of technology through adaptable design. For example: the relationship between the flat pages of a book and the projections that can be laid over them, or between a child’s first encounter with a book character and the possibility that they might be able to play with a digital version of that character. But we must be careful to not fall into gimmick. How can we design with flexibility and transition in mind? And, alongside this, how can elements of chance encounter, of tactile encounter with the pages of a book, endure?

Foster + Partners’ approach identifies that community-centred and adaptable design is essential in creating a space that people will continue to use. Considering the library of the future, Evenden continues:

In our experience, overlapping uses creates a richer programme that promotes learning and fosters flexibility that will allow the building to meet future needs and changing patterns of learning. The flexible nature of a library’s design is also increasingly important in terms of its potential for adaptive re-use as well as overall longevity and sustainability.

Designed in ways that embrace our changing structures of knowledge, the library has evolved to accommodate a wide range of multidirectional and multiform experiences. Ultimately, as each of Foster + Partners’ library and library-adjacent projects demonstrates, the library must be a place for people – for without people, no encounter occurs. We understand ourselves through the stories that we tell. The spaces that hold these stories, then, must understand us. This is the true task of the library architect: creating a space where researching, daydreaming, questioning, communing, remembering, are all possible experiences held on a ‘boundary between.’

Bibliography

Lehamnn, Steffen. Reimagining the Library of the Future: Public Buildings and Civic Space for Tomorrow’s Knowledge Society, Oro Editions (San Francisco, 2022)

Lopez Garcia, Antonio & Bueno Guardia, Miriam. ‘Typology and Multifunctionality of Public Libraries in Rome and the Empire’. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies (2021)

Murray, Stuart. The Library: An illustrated history, Skyhorse Pub. (New York, 2009)

Warpole, Ken. Contemporary Library Architecture: A Planning and Design Guide, Routledge (London and New York, 2013)

Narbo Via, Archibooks (Paris, 2021)

The Architecture of Knowledge ed. Netherlands Architecture Institute, NAi Publishers (Rotterdam, 2010)

https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/architecture/reading-room

Author

Clare St George

Author Bio

Clare St George is the Assistant Editor at Foster + Partners, where she works across a range of publications – from concept-based design stories to the granular detailing of a project or methodology. She obtained an MPhil in Criticism and Culture from the University of Cambridge and a BA in English Literature from the University of Oxford, during which her research orbited ideas of spatial form, interdisciplinarity, and narrative structure.

Editors

Tom Wright